My Mother Ethel

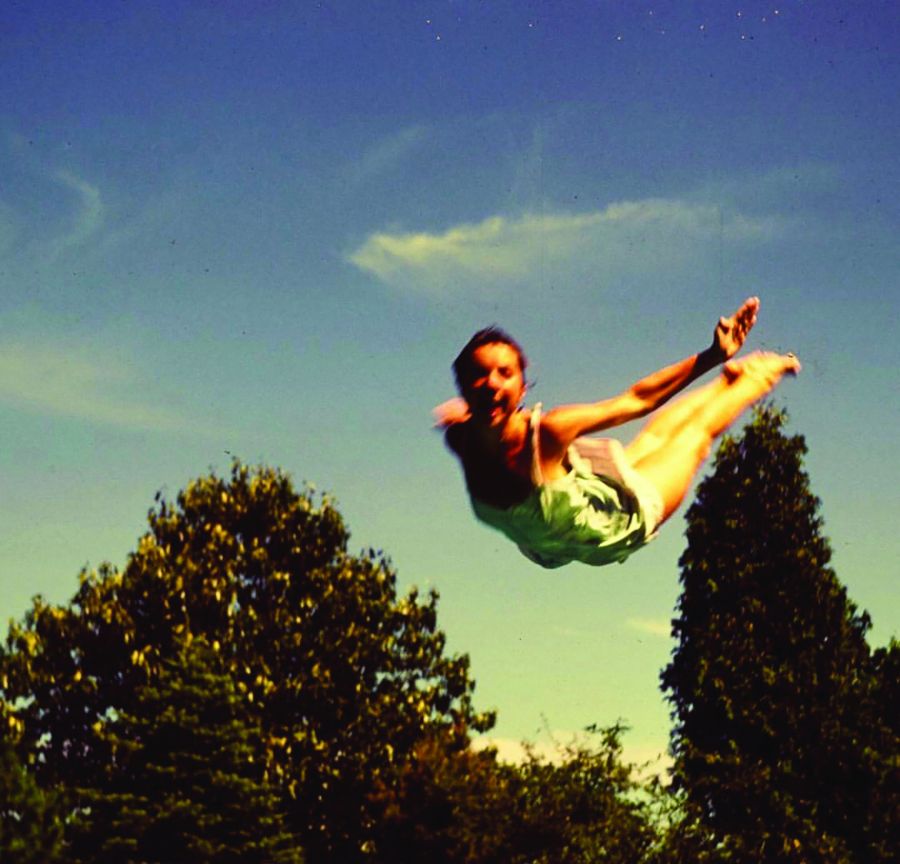

Ranked among the world’s best amateur female tennis players, she could catch a football while sprinting and could hit all the keys on a piano with just five digits.

Compelled Cabinet members to play charades, freeze tag, capture the flag, kick the can, and to climb ropes, do push-ups, and fence with bamboo sticks over the swimming pool.

‘Both segregationist governor George Wallace and civil rights leader Vernon Jordan told me how much it meant to them that my mother was among the first at their bedsides after they were shot.’

My mother was the sixth of the seven children of George and Ann Brannack Skakel. Her father grew up on a South Dakota homestead spread, never graduated high school, rode the rails to Chicago at age 14, and made a fortune in the carbon industry. He was a workaholic with a gift for numbers and a genius for turning muck into gold. During the Great Depression, there were 24 known millionaires in America. Joe Kennedy was one, George Skakel was another. My grandpa Joe was F.D.R.’s largest contributor and held three government appointments during his administration. The Skakels were, in contrast, oil and gas Republicans. Grandpa George rarely spoke disparagingly, except concerning Democrats, labor unions, and Franklin Roosevelt, all of whom he loathed. Grandma Ann was the daughter of a giant jut-jawed Irish cop in Chicago, who had a knack for spending moolah nearly as fast as Grandpa made it. Her children called her “Big Ann” because of her big personality, because she stood six inches taller than her husband, and weighed north of 250 pounds. She gained ballast with each of her seven pregnancies and never relinquished an ounce.

While Grandpa George was taciturn and laconic, Ann was intensely pious and devoted to the Catholic Church, but also loud, garrulous, and capricious. Thanks to her muscular version of Catholicism, there were pictures, statues, shrines, and religious iconography in almost every room of their home. My mother remembers their Greenwich estate as a happy, cheerful place, alive with the same species of boisterous chaos over which she would later preside at Hickory Hill. The 28-room home was a blend of The Philadelphia Story and The Beverly Hillbillies. The estate was filled with animals, including 300 chickens; assorted cows, goats, pigs, and horses; and 16 Irish setters — all named Rusty, and all of whom slept in beds with the Skakel children and Big Ann. My mother described her mom as “Julia Child before there was a Julia Child.” Grandma hosted and cooked for over 20 dinner guests each night. Like all Skakels, Grandma Ann was extraordinarily generous, prone to extravagant gestures and impulsive gifts. If you admired something she was wearing, she would give it to you.

My mother inherited Big Ann’s fervent, missionary Catholicism, her lack of fiscal discipline, her generosity, inclusiveness, and love of houseguests. She was also a gifted athlete who played every sport well. Like her brothers, she was a marksman with a rifle or shotgun. She was ranked among the world’s best amateur female tennis players. She could catch a football while sprinting, and she threw like a man. She excelled at golf, with a long drive and a murderous putt, but she was also good at baseball and kayaking, snow skiing, waterskiing, skating, and sailing. At age 11, she won the Larchmont regatta against a field of fifty boats, all sailed by older skippers. She was also a world-class equestrian.

Riding her dark bay Quarter Horse, Beau Mischief, she bested the women’s world high-jumping record, clearing a seven-foot-nine-inch rail at a jumping competition in Old Westbury, Long Island, in 1947. Her friend Lady Dot Tubridy, a fellow equestrian, hunter, and show jumper, told me that “if women had been allowed to compete in equestrian events at the Olympics, Ethel would have been on the US Olympic team.”

Horsemanship and sailing were not my mom’s only skills. Under Big Ann’s watchful eye, she unwillingly endured piano lessons for ten years with Dr. Carlos La Diabanco, who had somewhere lost three fingers on his left hand and two on his right, accounting for my mother’s odd style of hitting all the keys with just five digits.

At the Academy of the Sacred Heart in the Bronx, Sister Garafalo taught her the art of tap dancing, which she mastered with sufficient dexterity to hoof her way to parochial school stardom in the school’s senior-class musical. In later years those talents served her, and disquieted her children, whenever she trotted them out during those mercifully few occasions when circumstances invited. Even into her late seventies, despite her mediocre voice, it was an easy prompt to get her to sing and tap.

My mother had an irreverence for authority and habitual impatience with petty rules that started early and would remain lifelong traits. Along with riding and prayer, the young Ethel Skakel filled her days with tiny acts of disobedience. At Manhattanville College, she neither studied nor read much beyond the Belmont tout sheets. She engaged a bookie, studied the racing forms daily, and played the horses. Skipping class, she attended the track several afternoons a week when Belmont was open. Since car ownership violated college rules, she parked her 1917 Pierce-Arrow convertible off campus.

Manhattanville’s disciplinary records show that my mother earned demerits for “chewing gum,” “tardiness,” “clowning,” “disrupting the tea room,” and “combing her hair in public.” She had 28 demerits, compared to the 21 of her roommate — my aunt Jean Kennedy. “I beat Jean,” she told me with satisfaction. When, in her junior year, my mother racked up too many demerits to go to the Harvard–Yale game, she and Aunt Jean burned the demerits book in the school incinerator. “Why would they keep it right next to the furnace?” she asked me. “It was an invitation!”

My father and mother met during a winter ski trip to Mont-Tremblant, in Québec, introduced by Jean Kennedy, who had conspired with my mom to unite their families. The two families seemed ideally matched, with their shared Catholic piety, their proficiency in sports, and their love for outdoor adventure.

After my father fell for my mother, they embarked on what Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., described as “one of the great love stories of all time.” My dad loved her fiery spirit and was intensely proud of her reckless competitiveness and athleticism, her self-confidence, her humor, and her peculiar blend of deep religious faith and mischievous irreverence. Her fearless, fun-loving, outgoing personality perfectly complemented my father, providing encouragement to a man who was inherently quiet, vulnerable, and shy. Her devotion to him became a platform for his growth as a public leader. Whereas Uncle Jack was detached and deliberative, my father burned with passion. She fueled those flames.

My parents were so affectionate with each other that they often appeared pasted together, arms draped over each other’s shoulders, kissing and calling each other “sweetheart,” “darling,” and “honey.” I had an early allergy to corniness, and these antics would have put me in anaphylactic shock had they not been so genuine, casual, and adorable. They held hands when they ice-skated or walked on the beach.

On river trips they lay against each other beside the campfire. He proudly introduced her at his speeches, and she always took the front row and hung on every word, even after hearing the same stump speech a hundred times. She sat behind him in the motorcades, and he would look around whenever he lost track of her. He told reporters that his greatest achievement was “marrying Ethel.”

While my Uncle Jack was dispassionate and judicious, my Mom and Dad shared a Calvinistic moral sense. They both saw the world as a Manichean struggle. But next to my mother, my father seemed equivocal. While my father might grant the benefit of the doubt to his enemies and critics, my mother was unforgiving. If politics had been a real war, she would have been out on the battlefield, slaying the wounded.

Reporters knew to steer clear and dodge her calls after writing something uncomplimentary about my dad. Even when my dad refused to say bad things about J. Edgar Hoover or Lyndon Johnson, my mom was rapier-tongued and unforgiving. She ducked when Lyndon tried to kiss her cheek at my father’s burial. When Eugene McCarthy tried to console her after my father’s death, she brushed him aside, still hot from his earlier slights.

When Senator Joe McCarthy’s Chief Counsel Roy Cohn took a swing at my father outside a Senate hearing room, my father dodged the blow and Cohn, to his credit, later acknowledged that he was lucky that my father had declined the opportunity of a fistfight, one that Cohn would have certainly lost. While my father retreated, newspaper reports of the incident described how my mother needed to be restrained by friends from getting in her own licks.

From their first encounter on Mont-Tremblant, my mother fit in with the Kennedys. Lem Billings described her as “more Kennedy than the Kennedys,” and my father’s siblings embraced her like no other in-law. Coming from a family that favored boys, my mother was impressed by both the strong, independent Kennedy women and the respect their brothers and father accorded them. “It was remarkable to me that in this family, the girls’ opinions counted as much as the boys’,” she recalled. Unlike other Catholic fathers of his time, Grandpa Joe insisted that all his daughters attend college and find jobs, rather than wait for a husband. The Kennedys also introduced her to Democratic politics, an affiliation that eventually led to a long estrangement with the Skakels. “My family thought I’d turned into a little communist.”

In Jack’s 1946 congressional race, my Mom showed her nascent skills as a retail politician. She told me, “We would drive up to Boston and canvas door-to-door, then lick stamps. I thought, This is so exciting! I was rubbing elbows with people I’d never encountered. A lot of them were minorities and financially challenged people. Best of all, we won!” The poverty and prejudice she encountered challenged assumptions gleaned from her revered father about the evils of government intervention. “For the first time I started thinking, during this campaign, ‘These are people who face a lot of hardship and struggle, and if the government can help, then that’s a good thing.’” And she loved the diversity: “It was fun mixing it up and all being on the same team.”

In 1952, my mother took a much greater role in Uncle Jack’s statewide senatorial campaign against the seemingly invulnerable 12-year incumbent Henry Cabot Lodge, a pillar of Yankee blue-blood. With my grandmother in tow, my mom and my Aunts Pat, Eunice, and Jean hosted their famous Kennedy ladies’ tea parties in towns across Massachusetts. Ladies from blue-collar families in Fitchburg, Leominster, Fall River, and Amherst would put on their Sunday best for tea with the Kennedy girls. Each of the girls hosted up to nine tea receptions every day, serving a total of 74,000 ladies over the course of the campaign. My mother went into labor while she was giving a speech in Fall River. Undeterred, she drove to Boston, delivered my brother Joe, and returned to the campaign later that week. With the exception of another quick break to christen Joe in Hyannis, she worked every day until election day.

Jack’s Senate win was one of the few Democratic victories during Eisenhower’s 1952 national Republican landslide. Jack won by a margin of 75,000 votes, and Lodge later claimed that the Kennedys drowned him in “75,000 cups of tea.”

During the 1960 presidential campaign, my mom disappeared to West Virginia for six weeks and then campaigned for Jack across the country. After Jack’s inauguration she presided over a satellite White House at Hickory Hill. Her famous parties shattered the stodgy protocols of Washington decorum. “People were uptight and too concerned about how they appeared,” my mother remembered. To cure this contagion, she coaxed notables of different backgrounds into unfamiliar situations. A wizard at peer pressure, she compelled her guests to play charades, freeze tag, capture the flag, and kick the can, and to join in rope climbing and push-up competitions. She had Cabinet members fence with bamboo sticks on gangplanks spanning the pool. Something in her personality persuaded them to go along with it all. When Robert Frost visited Hickory Hill after Uncle Jack’s inauguration, she made him judge a poetry-writing contest among government officials and celebrity guests.

In a game of sardines, six-foot-six mountaineer Jim Whittaker climbed into a tiny hat cabinet above my mother’s wardrobe closet. Marie Harriman, who was on the evening side of 65, hid under the piano and was soon joined there by most of the president’s Cabinet. Governor Harriman chose a coal bin in an unlit basement storeroom, which, according to my mother, “smelled like a dead rat.”

My mother was crucial to my father’s recovery after Jack’s death. She gently pushed him toward reengagement. To give him a stable platform upon which to rebuild his life, she kept a sense of order and normalcy at Hickory Hill. She helped him recover through the example of her faith that Jack was in heaven, by ensuring that the children were cared for, and by her vigilant effort to rid our house of any evidence of sadness or mourning.

My father and mother also shared a conservative nineteenth-century sensibility that children should be toughened by constant exposure to the elements and physical challenge. Wilderness and adventure, they believed, would imbue us with character as well as beef-jerky toughness; it would awaken our souls and instill in us the range of virtues that European Romantics associated with the American woods — self-reliance, Spartan courage, and humility. Both our parents urged us to challenge ourselves and take risks. My mom and dad didn’t want their children to become indolent or diminished by privilege. They expected us to endure the exhausting climbs and occasional long days on a cold river in frigid rain with appropriate stoicism. Yet they both had ways of making the suffering seem fun. Using poetry and stories, they convinced us that we were all part of some noble adventure!

It would be many years before I came to appreciate the gifts my mother gave me, or the energies she devoted to keeping our family of 11 children together and on course after my father’s death. From my angle, her love didn’t always feel unconditional. Her approach was what today people would call “tough love.” She understood that “I love you” and “No” could be part of the same sentence. I proved a tough audience for this parental strategy. Her exceptional qualities were therefore mainly invisible to me as a child. I was in constant rebellion against the rigidity of her rules and her apparent capriciousness in their application.

It was not until I got sober at age 28 and began my own family that I finally began to appreciate the extraordinary qualities in her character. Though I hadn’t always noticed it, my mother had never faltered as my biggest champion. She always put her children first. Jinx Hack, her secretary from 1965 to 1967, who recalls the stint as “the best job ever,” says that my mom only got angry at her once — when Jinx, overwhelmed by a flood of visiting celebrities, forgot to pick me up at school. My mother, returning from carpooling my sisters, scolded her, “I don’t care if it is the Pope or the president, my children come first.”

I always knew that in the event of a serious calamity my mother would always be there for me. There was nobody kinder when you were in a jam — particularly if you were injured. My mother was more concerned about our wounds and broken bones than we were. When someone tumbled from a roof, horse, cliff, or tree, or smashed up a car, she would never ask, “Who was at fault?” but, “Are you okay?” I can’t count the times she made the familiar drive to the Georgetown Hospital emergency room and waited patiently — often sleeping overnight in the hospital chair — until we were discharged.

Over the course of her life, my mother’s genuine concern for anyone who was sick or injured became legendary. Given her partisanship in this regard, this concern was remarkably ecumenical: Both segregationist governor George Wallace and civil rights leader Vernon Jordan told me how much it meant to them that my mother was among the first at their bedsides after they were shot. Her close relationship with CIA director John McCone was rooted in the quiet care and devotion she gave to his dying wife, visiting her daily on her sickbed. After Sunday mass in Virginia, she regularly drove us to visit Jack’s PT-109 boat crewman Barney Ross, an invalid from a motorcycle accident, or to feed shut-ins at senior homes and soup kitchens. Every summer day she brought a lunch to Putt, a disabled World War I vet made mute by poison gas. She attended every funeral for every friend who died, and was disciplined about writing thank-you notes and long heartfelt consolation messages to people who suffered loss, many of whom she had never met.

As I got older and had six kids of my own, I became mystified about how she had managed. How did she possibly get eleven mutinous kids to show up for dinner on time? To ask to be excused? To attend daily mass? To pray together before and after each meal? To assemble nightly for Bible readings and rosaries? How did she keep our dinner table conversation elevated and inspiring? How did she, in all the hurly-burly, get us to play games of history and memorize poems and read all those books to broaden our intellect? Or to take summer jobs in environments that exposed us to the hardships endured by less fortunate communities? And how did she keep her strength amid the havoc and tragedy? When people asked how she coped with the violent and untimely deaths that claimed both her parents, her three brothers, her husband, and her two sons, she would say with a smile, “Everyone takes their licks.” As she told me, “We feel like we ought to be able to write our own scripts to our lives, and sometimes we feel disappointed in God when life rewrites the plot. The key is acceptance and gratitude. We need to practice wanting what we’ve got, not what we wish we had.”

Her early Catholicism, like her mother Ann, was rigidly orthodox, stressing obedience and ritual. But after my father’s death she reoriented her religion around his ethical concerns and the ethical precepts of Christ’s Gospels, which both she and my father equated with the noblest and most idealistic vision of America. Her own life became a cavalcade of causes along my father’s trajectories: justice for African Americans; Native Americans; farmworkers; people with intellectual and physical disabilities; victims of torturers, death squads, and despots; and, ultimately, LGBTQ people everywhere.

She confronted dictators and walked picket lines. She called congressmen and governors and senators and corporate CEOs and cabinet members and heads of state on behalf of the poor. She became an authentic force for good in her own right.

When the Nixon administration in 1970 tried to forcibly expel several hundred Native American activists who had occupied Alcatraz Island, my mother took a small boat to the old prison to join the protest. She helped the protesters prepare communal meals, held one mother’s hand as she delivered a baby, and called the White House to ask President Nixon to relax rules that blockaded food and water.

My mother was with César Chávez when he broke a 30-day fast in 1970, and again following his 24-day hunger strike in 1972. In 1983, she drove my younger siblings — Rory, 13, and Douglas, 14 — to picket the South African embassy in DC to protest apartheid and watched with pride as they were arrested. My mother joined Rory and Douglas on another picket line in front of the Chinese Embassy on a cold rainy night in October of 1989, protesting the Tiananmen Square massacre. My mother worked closely with the CoMadres in Guatemala throughout the 1980s, protesting the CIA’s war against the poor in Central America.

She was tough on left-wing dictators as well. In 1987, she visited Lech Wałęsa and Solidarity leaders in Poland with Joe, Michael, Kathleen, Courtney, and Kerry. She made it her mission to support democratic movements against Communist regimes in Hungary, Albania, and Czechoslovakia.

In 2001, my mother visited me when I was jailed for 30 days in a maximum-security prison in Puerto Rico for committing civil disobedience in protest of the naval bombing of Vieques. She told me how proud she was.

She made many trips to Cuba to convince Fidel Castro to release dozens of political prisoners. She confronted the murderous and volatile Kenyan dictator Daniel arap Moi in a heated exchange in Nairobi.

Every year, I’ve come to a deeper appreciation of my mom’s colorful qualities, and her place at the center of history. She remains one of the funniest, most exciting people I have ever known. I was lucky to have her as a mother and my kids felt privileged to have her as their grandmother. Over the past three decades, my mom spent her summer evenings sitting patiently at a long children’s table on the outside porch in Hyannisport as the sun was setting and the Atlantic was shimmering behind her, presiding over dinnertime with dozens of little grandchildren, competing with them at word, history, and math games. Afterward, they alternated in playing backgammon with her. Many parents deliberately lose to their children in these kinds of contests. Not Grandma Ethel. She took no prisoners in any competition: “I think it’s more fun that way, because then, when they do win they know that they have earned it. It helps them learn to concentrate, and of course be lucky.”

“Also,” she would add, “I don’t like to lose.”

I’ll close with two brief stories that illustrate my mother’s signature appreciation for mischief.

In 1949, during the International Horse Show in New York, my mom engaged in a scheme with her best friend Dot Lawlor, both 19 at the time. My mom masqueraded as a New York Times reporter to interview Lord Michael Tubridy, a Gaelic football star and champion show jumper whose peerless horsemanship and movie-star good looks had excited world attention from the media and school-girl crushes in Dot and my mom. Lord Tubridy immediately recognized the hoax and walked out of Schrafft’s ice cream shop where my mother had arranged the “interview.” In revenge, Dot and my mom sneaked into the Madison Square Garden stadium and dyed Tubridy’s white jumper with indelible green food coloring. Tubridy rode to the championship on an emerald stallion. In the end, the ploy worked. As it turned out, Lord Tubridy had a sense of humor and married Dot Lawlor a year later.

In 1952, my mom, Eunice, Pat, and Jean traveled with my father to St. Petersburg. The Soviet Union had invited them to be the first Westerners to tour the Hermitage Museum since World War II. Before she left, the CIA outfitted my mom with a tiny camera concealed in a corsage with which she snapped some two hundred photos of the artworks stolen by Nazi officials from German Jews and French citizens and subsequently confiscated by the victorious Red Army.

Patriotism undoubtedly inspired my mother to take on this high-risk and seemingly reckless espionage project, the penalty for which was life imprisonment or execution. It’s safe to speculate that the exhilaration she derived from any dangerous mischief was also a motivating factor.

In the summer of 1992, a decidedly tipsy dinner guest leaned in and gushed to my mother over dinner, “I’m so happy to be invited here.” Embarrassed by his wife’s condition, her husband endeavored to bridge the awkward silence that followed by cautioning her, “If you behave, honey, you’ll be invited back.” Without missing a beat, my mother assured her dryly, “If you misbehave, you’ll be invited back sooner.” That pretty much summarizes my mom’s gestalt. A needlepoint pillow in her home recites her guiding principle: “If You Obey All the Rules, You Miss All the Fun.”

Weren’t we all so lucky to have known her for 96 years?