Eight Dollars

A hayseed’s adventures in the old Times Square

Robbed in an elevator by a straight-razor-wielding dwarf

Double the pleasure in adjoining dental suites

Times Square in the 1970s was in some sense the heart of Grub Street, “the world of literary hacks, or mediocre, needy writers who write for hire.” The New York Times, which lent its name to what was then the world capital of cheap porno theater seediness, was the voice of Grub Street, grown rich, obscenely complacent, and obliviously self-assured.

Now picture a Caucasian hick in his early twenties, hayseeds in his socks, with a 60s Canadian haircut and a Maoist-issue canvas proletarian man-purse, moving to NYC to pursue a literary career without a college degree, or high school diploma, friends, or work experience outside the Forest Products industry. The choice might seem imprudent, but such decisions, like going fishing, or on a crusade, are never rational. If my decision to move to New York was motivated by any form of sentient reasoning, it was the product of a self whose desires and fears are no longer recoverable in detail, having been long ago plastered over by the varied and often-tangled motives of successor selves whose transient needs and purposes were in turn the products of bygone alignments that no man alive can remember, and certainly not me.

What I do recall is that I’d read Balzac and Proust and wanted to be a writer, and that being paid for anything other than cutting wood was acceptable. As for prospects, I had sold "a couple of articles" (i.e. two) to a new magazine, National Lampoon, with new offices at 635 Madison Avenue. I had earned enough money chopping trees in a British Columbia logging camp to arrive at The Times Square Motor Hotel and pay a month’s rent in advance.

The Times Square Motor Hotel was an anachronism run by a man named Arthur Schwebel, who took over the hotel in the 1960s, and added" Motor" to the name. Self-described as “a moderately priced hotel with free parking,” Schwebel’s hotel — with its long marble-topped reception counter, brass carpet runners, and uniformed staff — persisted long after the public Schwebel meant it to serve had vanished.

Schwebel quaintly kept up the standards of the 1950s in a 1970s urban combat zone. The enormous, black, heavyset sort-of-doorman, Ernie, was also “Hotel Security.” Ernie generally rested his mammoth bulk on a broad wingback armchair parked near the elevator bank in the hotel’s massive lobby. When the clerk at the vast, mostly unmanned reception desk handed a room key to a new monthly resident, he advised: "Rent is due on the first. You get three-days grace if you warn us you'll be late. Any more than that, maintenance puts a plug in your door. You’ll have to see the manager and pay off back rent before it's removed.”

In addition to my naivete and the first month’s rent, I had one other asset to deploy. I had worked for a small publishing company in Canada, and in parting they gifted me a years-overdue account receivable for books purchased by the Black Panthers’ Liberation Bookstore, on 125th street in Harlem. The bookstore owed the publisher, and now me, for 1,000 copies of The Minimanual of the Urban Guerilla, written in 1969 by Brazilian revolutionary Carlos Marighella. The account was more than 180 days past due, with terms stated fair and clear on the invoice, brother.

That money was mine, as soon as I could get up to Harlem and collect it.

Douglas C. Kenney, an editor at National Lampoon and my friend, referred me to a dentist, Gary Dean Soldati, who had a fancy 5th Avenue practice where he would anesthetize patients and drill cavities. On the day of my appointment, Soldati sent his assistants to lunch and administered nitrous oxide and IV sodium pentothal on me, in addition to the usual local anesthetics. This combination of drugs is sufficient to render most people deeply unconscious; however, heavy drinkers, as I was, are often resistant to sedation.

“A strange thing happened at the dentist you referred me to, Doug. I dreamt the dentist was blowing me. I awoke, and he was.”

Doug considered this for a second, then said, “I told you he was weird.” We both started laughing. We wrote some stories together for the magazine, stories which became my CV when Doug died, at 33, in a fall from a Hawaiian cliff. Where, Michael O’Donoghue said, “he had fallen, looking for a place to jump.” Many of us then used cocaine to cover an inability to come to terms with the world, to reconcile the harshness of commerce, the brutality of war with our own beliefs about what was right and possible. The world was a slippery place, and the crash was terrible.

I took the subway up to 125th street in Harlem. My Mao bag was stuffed with past-due invoices and some sample books of poetry with a revolutionary flavor. As a comrade in the struggle against all forms of oppression, racial and religious bigotry, I was prepared to offer generous terms to settle the overdue account. The staff at the Liberation Bookstore told me the manager was out, and only he could authorize payment. Since he was, in their view, unlikely to do so, I should therefore get the fuck out of the store. I promised to return to see the manager, left a couple of poetry chapbooks, and got the fuck out of there.

Heading back to the subway I was surrounded by street urchins who followed me to the subway entrance, reminding me I was of the oppressor ethnicity by pronouncing me a honkey motherfucker. The pack broke off at the subway entrance, but one child followed me down and out onto the platform.

"Hey mister," he said," do you know why those kids called you those names?"

“You tell me,” I said.

"Ray-shull prejudice," he said sadly. We smiled, pleased to be not that, at least with each other.

I went back to the Panthers’ bookstore a week later in hope of catching the manager, but my reception was sufficiently unfriendly and discouraging; enough so that I agreed to settle the whole account for $8.00, about half what was in the till. Years later I would meet Dr. Snakeskin, a.k.a. the author Darius James, who was managing the Liberation Bookstore at the time and had heard all about the hayseed debt collector and had been amused. Sela. The point of this story is the $8.00 collected, as will be detailed further below.

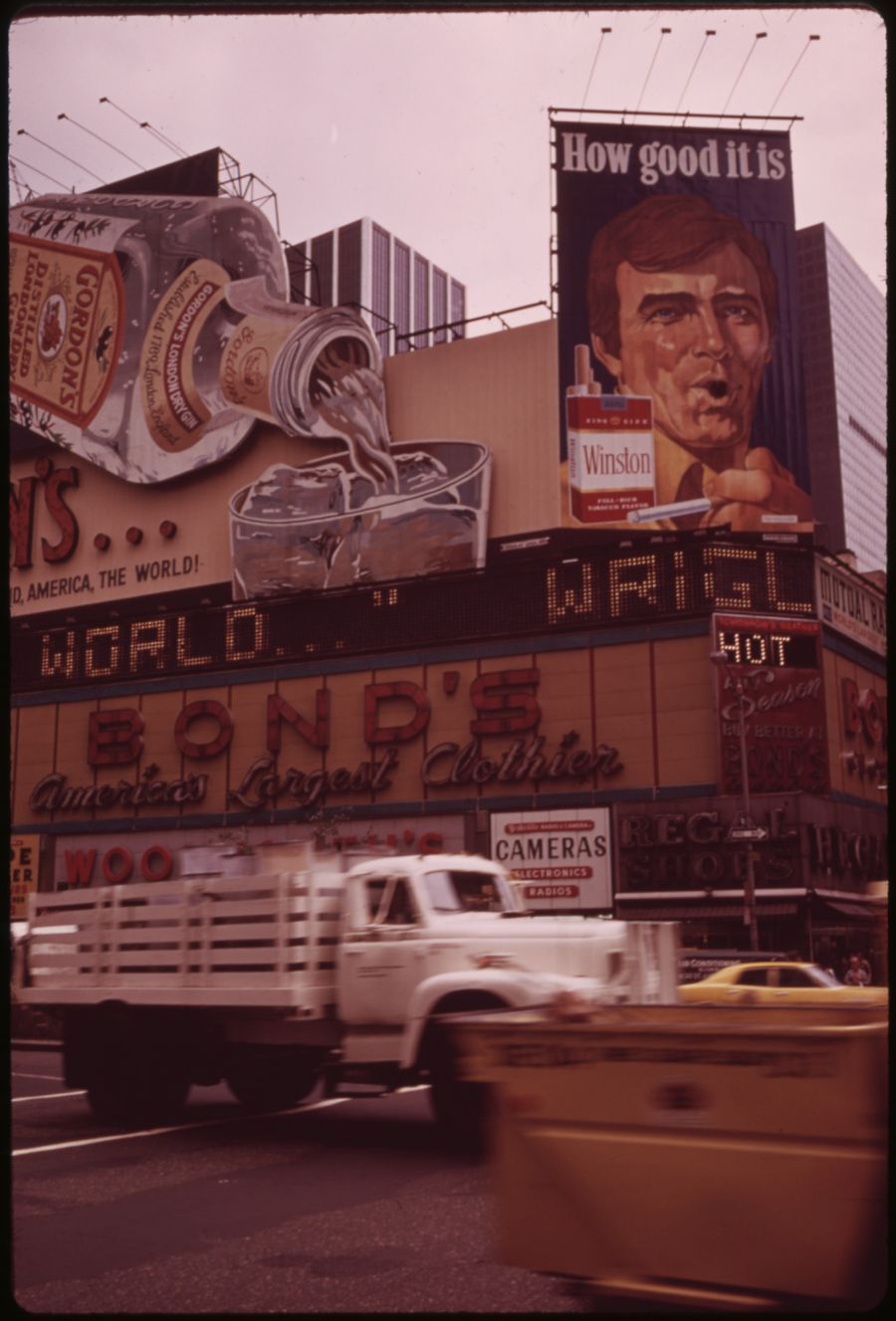

Returning from Harlem via the 7th Avenue line, I got off at Times Square emerging against traffic — the local office workers, sweatshop cigar rollers, and New York Times hacks all heading home by 5. At dusk, the previously mentioned Dr. Snakeskin observed, the Popeye of the Popeye’s chicken sign changes complexion, just as Times Square does, the population changing from white to black. The theaters on 42nd Street also reflect this change, the grungy marquees lighting up with blaxploitation titles like Dade County Sheriff, Dolemite, Coonskin, and The Spook Who Sat by the Door.

Sometimes on hot days there’d be dirt twisters. Small cyclonic storms, generated by radiant pavement heat and rectilinear geometries of urban architecture, would spin up from a combination of fetid gusts. And so the Times Square Dirt Twister was born. As they traveled, they would suck up the empty cocaine packets, band-aids from dilating trannies, fast food wrappers, and carmine-lipstick-lipped cigarette butts. The whole mess, maybe 15 feet tall, would wobble down the block, with pedestrians diving into doorways, scurrying before the erratic twisters reached them, which sometimes veered halfway across the street before turning back, undecided. The whores cursed and clutched their bags unwilling to abandon their posts on account of any weather, protecting their spots until the thing passed, eventually to topple exhausted, dumping its burden of detritus on the street or the sidewalk in a sudden heap. Meanwhile, a continuous stream of wankers entered Show world, the mob’s anchor tenant on the ‘deuce.

Crossing the lobby of the TSMH I waved to Ernie the guard, and got into an upward-bound elevator, noticing, as the door closed, another passenger, leaning against the back of the car, eyes closed as if asleep. My fellow passenger was a little person, not normally proportioned. Technically, a dwarf. The dwarf came to life, produced a straight razor, and waved it at my throat which he could easily reach in a single agitated hop.

He demanded money. When I gave him the $8.00, he stared indignantly at me, before he thrust a little hand into each of my pants pockets in turn. The elevator had by then passed my floor. The dwarf punched the 6th floor, and got off the elevator cursing, and moved off down the hall, ignoring me as the door closed. I pushed the button for the lobby.

“Ernie,” I said, “I was just robbed by a dwarf with a straight razor in the elevator.”

Ernie needed no further description. “That son of a bitch. I told him what was gonna happen if he pulled that shit in here. C’mon,” Ernie said and headed for the elevator.

“How much did he get?” Ernie asked.

“Eight dollars,” I said. Ernie shook his head.

We rode up to the 6th floor and Ernie, whacking his thigh with his lead-loaded billy, led the way down the hall. “He’s a junkie,” Ernie told me, and pounded his stick on the door. “Open up, Hotel Security,” Ernie shouted, and from inside we heard shuffling. “Go away, I’m asleep,” said someone inside. Ernie popped the door with his passkey. The dwarf was in bed, feigning sleep.

“I’m sleeping,” the dwarf insisted, “what’s this about?”

“This guy said you robbed him in the elevator.”

“Bullshit, I’m fast asleep until just now!”

Ernie picked up a cup of coffee from the dwarf’s nightstand. “You drink hot coffee when you sleep with your clothes on, you lyin’ little bastard!” Ernie whacked him with the billy. The dwarf doubled over.

“Let’s have the $8.00. Cops are gonna take what you got anyway so hurry the fuck up.” Ernie gestured with his billy, abbreviating the dwarf’s period of reflection. The dwarf reluctantly fished around in his pocket, and produced some crumpled bills. Ernie passed them to me. “Take your $8.00, take whatever you want.”

I picked out $8.00 and handed the rest back to Ernie. “You leave the cops to me.”

Ten days later I appeared at the courthouse, per subpoena, ready to testify. The dwarf, who’d been released on his own recognizance, did not.

The harassed ADA showed me the dwarf’s criminal rap sheet, it was 12 pages long. There was a warrant issued for his arrest. My interest in the matter had long faded from memory when I received a call from an assistant district attorney, 5 years later, informing me the dwarf had been rearrested for stabbing a pregnant prostitute, killing her and the unborn child.

The ADA in charge of the case told me they’d get a conviction on the murders, they had a dozen eye witnesses. However, the murderous dwarf was an exceptionally heinous little shit, so they wanted a conviction on the 5-year-old straight razor robbery as well. I agreed to testify against the dwarf and I did. I swore I recognized him after five years, whereupon the dwarf’s defender pounced.

“You are able to identify my client after a two-minute encounter in an elevator five years ago? You must have a phenomenal memory!” his female public defender charged.

I likely smiled. Someone on the jury laughed. The judge said, “No disruptions!”

The dwarf’s attorney swooped in for the kill. “You say you got on the elevator where my client was resting and pressed the button for the 4th floor?” It was so, I agreed. “Then perhaps you will tell the jury which side of the elevator those buttons are located on.”

The woman was fully prepared to gloat.

“The Times Square Motor Hotel may have passed her glory years,” I replied, “but she still has polished brass panels of buttons on both sides of the elevator.”

“I have nothing further,” said the attorney, before sitting down. As well she might. The dwarf got 30 years minimum to life, in aggregate.

Years after all this chaos, my ex-wife sent me a newspaper clipping. Gary Dean Soldati, a dentist, had blown his head off with a shotty in his Central Park office. Dr. Soldati was facing trial on charges of performing oral sex on father and son patients in adjoining dental suites.