King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard

What the hell is it?

The new Phish, crossed with prog rock.

It comes from Australia, where men wear resses, do yoga, and play the blues.

It’s Friday morning in Buena Vista, Colorado, and my tent is not cooperating. All around me is the tinny sound of other campers expertly pounding stakes into the earth with fun-sized mallets. I am using my left Birkenstock, and its forgiving cork-and-rubber sole is not faring well against the Rocky Mountain soil. It takes me over an hour to erect what resembles an overturned laundry hamper, by which point Meadow Creek’s Car Camping Area West, my home for the next three days, has been transformed from a grassy parking lot into a splendid tent city with row upon row of brightly colored canopies, camper vans, domed tents, and teepees. Their owners, seasoned campers all, have broken out their guitars and hung the requisite psychedelic tapestries and fired up propane grills. I have come here with my busted tent to join them for the first-ever Field of Vision music festival.

Here in Buena Vista, 9,000 people will enjoy three days of live music featuring White Fence, Babe Rainbow, Ryley Walker, and Shannon Lay — acts curated by the Australian rock band King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard, which is headlining every night with a three-hour-long marathon performance. There will also be DJ sets, drag shows, late-night movie screenings, and “acid” yoga classes (for heightened awareness of one’s balance during a prolonged kakasana).

If you’ve never heard of King Gizz — or if you have, but, based on the deliberate lunacy of their name, you’ve decided they’re not your cup of tea — know that they are less a band than a sonic ecosystem unto themselves. Since forming in 2010, the group has released 27 studio albums, although that number skyrockets if you include solo projects, live records, and various demos.

Though often hewing to a broadly psychedelic and prog-inflected sound, King Gizz’s music roams between genres as varied as metal, bedroom pop, garage rock, jazz, electro, and, occasionally, white-boy rap. They have released thrash metal concept albums that deal in environmental doomerism, and records full of desert-dwelling soundscapes played on custom microtonal guitars — as well as one that’s like an anti-spaghetti-Western audiobook narrated over what resembles the score for a long-lost Sam Peckinpah film. Last year, in the throes of an ongoing synth phase, they custom-made a giant modular Eurorack — nicknamed “Nathan” — which they now incorporate into their live sets. As many as five of the band’s six members will improvise on Nathan all at once, fondling its wall of knobs and patch cables.

To produce so many albums, averaging more than one release each year since their inception, King Gizz also started two separate independent record labels — which have served as suitable midwives for some of the best Australian rock bands of the last two decades.

If all of this seems a tad Spinal Tap-ish, well… You’re either into it or you’re not.

I first discovered King Gizz in 2017, when they released five full-length LPs in a span of barely eleven months, each of which was somehow an intricate concept album with a distinct aesthetic sensibility. At the time, I was a college freshman going through a bookish prog phase, an acolyte of King Crimson, and I became hooked on the polyrhythms and death-cult choruses of Polygondwanaland. I have since seen them perform live three times, not counting the heroic nine-hour dose I am taking this weekend.

And plenty of other people are into it too. Very into it. In recent years, a Deadhead-caliber fanaticism has begun to coalesce around King Gizz. In addition to the nine thousand or so people in attendance here, tensof thousands more will watch the livestream in real time. All of which makes Field of Vision slightly different from the spate of artist-curated festivals that have begun to dominate the summer calendar. This is a magnet for the band’s most rabid fans, and I have come as one of the faithful to watch it go down.

My brightly colored map of Meadow Creek resembles a lopsided butterfly. Campgrounds and performance spaces balloon out from the creek that winds through the center of the venue. As I walk beside the water, I appreciate the giant cottonwood trees and ponderosa pines that tower over the dirt path leading me to the main drag, the undeniable beauty of the landscape only slightly offset by legions of porta-potties and four wheelers bearing pink-shirted venue staff and security.

The Diagon Alley that has mapped itself onto this terrain has many offerings, almost all of them loosely King Gizz-themed, from the Timeland and Phantom Island performance stages to the p(doom) record fair (named after the band’s current label) to Mirage City — a sort of bazaar where people are selling DIY merch and bootlegs. The food, however, is not Gizz-themed. From the rows of white tents serving festival vittles, you can buy, among other things, “Polish Dogs” (bratwursts with kraut and a structurally unsound bun), drunken noodles, or a $2 cup of iced coffee, which costs $10.

The King Gizz fanbase is as eclectic as the band’s discography, and the myriad substrata of Gizz-heads are amply in my midst: There are the buttoned-up jam-band dads and the metal heads draped in chains and the dreadlocked back-to-the-landers, with all varieties of wooks and punks in between. There are also the less scrutable superfans. Passing through the outdoor cinema, I see a cluster of men in wizard cloaks and masks, who look uncannily like the orgy-goers in Eyes Wide Shut, except they are barefoot, laughing, and passing a joint around. It’s slightly surreal. I give them a little wave and they nod my way in unison.

Making my way down to the Timeland stage, I find Shannon Lay, a folk singer with hair the color of fire, playing one of the opening sets to a crowd that has comfortably spaced itself out on a bed of wood mulch. Although Lay used to play frenetic punk music with the band FEELS and was once a member of garage-rocker Ty Segall’s Freedom Band, her solo stuff is mostly a wispy brand of folk that I particularly like — more Nick Drake than Dylan. From a bridge over the creek, I find the ideal vantage to watch her set and ease into the festival weekend, following her falsetto as it drifts with the current. Some of my fellow festival-goers are sitting below me, among the reeds with their feet in the water, listening along. “If I were to know you / I’d show you all the little things,” she sings. “Call into the gloom / So we never have to leave.”

I look up. Gauzy clouds are suddenly amassing overhead, threatening rain. Perhaps Lay’s lyrics conjured up a storm? I turn to go shore up my laundry-hamper situation in the campground, and in my hurry I run into a gangly man walking across the bridge with a plastic trombone the color of a traffic cone. He is not in a hurry. Raising the instrument to his lips, he begins to march back and forth before me and plays a long, bending, farty note, which recedes behind me as I begin to run.

“You can color everything you see / It’s so strange / With cellophane, cellophane, cellophane…” sings Stu Mackenzie, the frontman and songwriter of King Gizz, his legs spread wide in a power stance under a grid of swirling green lights.

It’s now Friday night, and after a powerful stream of sweaty rave atmospherics, the band puts Nathan away so they can jam on a few beloved classics from earlier days. After all, a marathon set means a marathon set. There’s minimal banter, and no breaks between tracks aside from a medical emergency that occurs early on in the set when a man collapses in the crowd, prompting the band to immediately stop playing, call for medical attention, and leave the stage. Otherwise, each song unfurls into the next in a seamless flow of music that bounces from prog to metal to psychedelic stadium rock to techno.

Onstage, and within my ears, King Gizz has wed the nerdish musicianship of a world-class jazz ensemble to the dudely exuberance of hair-metal bands long past. This marriage’s most artful vessel is Stu, who shreds with the ardor of a Pentecostalist who has allowed the Holy Spirit to consume him. He sticks his tongue out and thrashes his head from side to side, before putting the entire microphone in his mouth and screaming, his arm swirling the air in slow motion, like a wizard conducting a tempest.

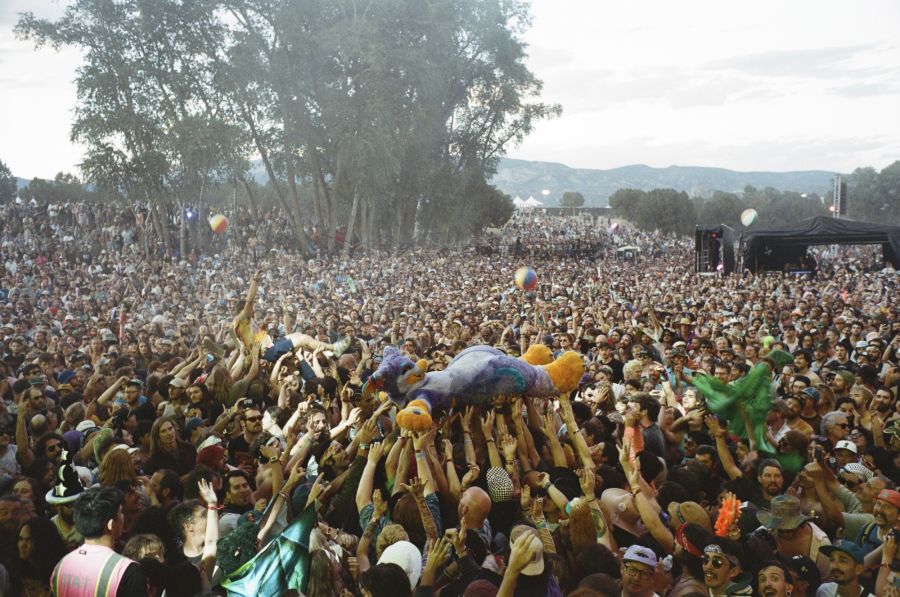

The main stage is packed from end to end. Some people are up on the slope to the side of the stage for a better view, dancing wildly in front of the porta-potties. Up in the region of the mosh pit, more revelers are pogoing and slamming into each other as many crowd surfers float toward the stage alongside inflatable reptiles.

I’m not the kind of guy who gets into a mosh pit. I’m the kind of guy who keeps one hand in his pocket and the other wrapped around a beer can while nodding along. Sometimes I do a little two-step. But, for the sake of journalistic duty, I have resolved to mosh at some point this weekend.

Not tonight, though. Tonight, I’m standing in front of the sound booth, a little off to the right, just close enough that I can see the band clearly without resorting to the jumbotrons that flank the stage. Now firmly in the heavy-metal portion of the set, King Gizz launches into “Converge,” which is a thrash dirge about environmental collapse, the twenty-first century’s answer to the wistful protest songs of the ’60s. There are a number of these in the Gizz catalogue. Born from a nihilistic acceptance of the reality that we are, on many vectors, fucked, they spin political angst into danceable metal:

Houses, cities, torn asunder

The havoc wreaked, a sight to wonder

May the lord have mercy on us all

Pray the storm which risen, thus shall fall

Stu continues to sing in the guttural voice he reserves for the gritty stuff as I wander to the outer rim of the crowd, which turns out to be its own kind of bacchanalia. With more space to maneuver, people are covered in glowstick jewelry and dancing with their whole bodies, summersaulting past one another in the grass. A woman is lying alone on the ground with a towel over her face, writhing playfully to the music as though possessed by a cheerful demon.

I awaken Saturday morning to the smell of sausage cooking on a propane-powered grill. I mooch a bite from my neighbor Anthony before I head down to the Phantom Island stage, where Jello Biafra, the former lead singer of Dead Kennedys, is spinning vinyl for the benefit of those of us who are up and moving before noon. A self-proclaimed Gizz super-fan, Jello is here this weekend playing a dual role as punk elder statesman and loveable groupie uncle. He joined the band on stage last night to sing the Kennedys’ hit “Police Truck,” and he’ll be delivering a spoken-word performance tomorrow afternoon. Right now, though, he’s set up on a grassy island in the middle of a small pond, playing hardcore and post-punk deep cuts, most of which neither I nor Shazam can identify.

People are lounging along the creek’s banks and absently floating about on inflatable swans and the like. It’s a pleasant scene, especially for the badly sunburned girl in a peasant dress next to me, who is sitting on a striped blanket and loading up a small bong as Jello puts on “Kill the Hippies” by the Deadbeats.

I wander over to nearby Mirage City, where the general atmosphere is a mix between a small-town farmer’s market and a Phish show parking lot (sans nitrous tanks and corndogs). There are three or four dozen booths arranged in two long rows, and clusters of people stand around carrying tote bags, with records and poster tubes jutting out at all angles. A couple of official merch vendors are on site at Field of Vision, but I personally find the expansive Gizzverse iconography to be better expressed in DIY form: Cartoon gators, Gila monsters, cloaked wizards, smiling lizards, the flying microtonal banana guitar, some ghost thing with a gas mask, the nonagon infinity symbol — all of these have been turned into pendants and stickers or stamped on tie-dye shirts.

I walk up to a table full of beanies with embroidered gators on them and fuzzy Christmas stockings that have “KGLW” embossed on the arches. The booth’s proprietress is Lindsay Borg, a short, bubbly woman with mid-length chestnut hair, who knits and sells Gizz-themed clothing under the name “Lizard Queen Stitchcraft.” She’s also an anesthesiologist at a hospital in Portland, Oregon, where there’s a sizable cohort of Gizz-head MDs. “We listen to Gizz songs while in the OR during operations, because, you know, we can listen to music,” she says. The Lizard Queen reaches over to one end of her table and picks up a brightly colored surgical cap patterned with cartoon gators. “So I also make these scrub caps, too, for the niche fans that work in medicine.”

What all of this adds up to, I think, is an instantiation of an American pastime that extends far beyond the confines of Mirage City. This is just what many of us do. We find something we love, and we put it on a T-shirt.

Stu Mackenzie is sitting across the table from me, wearing a baby-blue jumpsuit with pink sunglasses atop his head. We’re in the nearby Surf Hotel’s restaurant, a large stone and stucco building on the banks of the Arkansas River, where the band is staying for the weekend. Given his role of sorts as Field of Vision’s head chancellor, Stu, who is just shy of 35, is appropriately large, standing at well over six feet, but the thing that strikes me most about him is his surprisingly tranquil, approachable demeanor. If you Google Stu, you will see him holding his guitar at dangerous angles, often looking like he has just stuck his finger in an electrical socket. But in person he is soft-spoken and thoughtful, with expressive eyes that carefully follow your gaze as he speaks.

“The easier way to tell the story is that you get into one thing, and then you get into another thing, and then you get into another thing — but often you’re just listening to a lot back-to-back,” Stu says, when I ask him if the evolution of the King Gizz sound has tracked with his listening habits over time. As an 11-year-old with a tiny MP3 player, Stu listened to Dead Kennedys at the same time as the fanciful concept albums of the prog band Yes. “In some ways those things shouldn’t coexist, because they kinda represent opposites,” he says. “But I never saw it that way, at least when I was younger. I still try to not see it that way.”

We talk for a while about the festival, the band’s exploding popularity, and the many genres they’ve touched on in recent years. When I mention Phish and the Grateful Dead, which I do less to suggest a musical kinship than to provide reference points for worshipful fanbases, Stu is quick to say, “I would be personally careful about putting our name in the same sentence as some of those artists because it feels generationally different, whether there are some parallels and things like that.”

The mutability of the band’s live performance, the jamming, he says, grew less out of an affinity for any existing tradition than out of their desire to diversify their sets once people began to follow them around, which only began when they started touring in the US. “That was something that hadn’t happened to us in Europe,” he says. “It hadn’t happened in Australia at all.” If King Gizz has any debt to the Dead, it’s in the way that the earlier band set the pace for fandom in the States. “I’m pretty sure if they never existed, it would be much more similar to other places,” Stu says. “But the culture of driving for ten hours, driving for fucking twenty hours, flying from one side of the country to the other just to see a band — it’s what Americans do.”

I ask Stu about the recurring theme of techno-environmental collapse in his songwriting. For someone who, at least in his art, seems to dwell on the prospect of apocalypse, Stu is remarkably chipper and constructive. Without intending to, I confess to him that, at 26, I am often plagued by a gnawing sense that the party is over, which sometimes scrambles the calculus of my life decisions, like whether or not I will have children.

“Yeah, being a young person in a world that feels like it was fucked up before we got here is a tough thing to sit with,” Stu says, pouring us more water. But then he begins to talk about all of the good things in life that help him square the circle, like being a father. In April, Stu and his wife, Philippa, had their third child, a baby girl named Theodora. “We call her Teddy,” he says, his face lighting up. He also has a boy and another little girl, both born in the last five years.

“Being a parent makes you see things in the micro,” he says. “That’s actually good for people like me, who worry about other people’s problems. There’s something quite beautiful about just having things right in front of you to worry about and wanting to be the best dad.”

I ask Stu an obvious question, which is how he manages everything — how he juggles the touring, the songwriting, the recording, and the record labels, all while raising three kids and presumably sleeping for a couple of hours a night.

“Well, firstly I have an extraordinarily supportive wife,” he begins, laughing. He talks about how doing everything under one roof streamlines things, makes it easier.

“I know that might sound like we’re doing more work, but I’ve always found going directly to the source is a good way to do things,” he continues. “For the most part, we’re just getting together, making music, finishing it, putting it on wax, selling it, doing the next thing.” I ask if he knows what the next thing is.

“For me, at the moment, I am so locked into the modular synth — the Eurorack stuff,” he says. Discussing his dear Nathan, Stu speaks with the wide-eyed enthusiasm of a boy talking about his new Christmas present. “It’s kind of like… it’s rewired my brain,” he says. “It’s rewired the way I think about music.”

The band recently recorded a batch of experimental, synth-heavy material, Stu tells me, which they don’t have a concrete plan to release just yet. “We’re in a very deeply experimental phase at the moment,” he says. “It feels like panning for gold, honestly. You’re sort of just… in the stream.” He holds up his cupped hands, pantomiming a sieve. “It just takes time.”

I’m sitting with my legs crossed and my arms outstretched on Sunday morning, pretending that I’m holding up a giant rock. I’m one of maybe five hundred people here at Acid Yoga, getting loose before the day’s festivities. Last night’s set was heavy on the synth and metal, and after two days of standing for twelve hours straight, a slow moment feels right.

Our instructor, a slim Australian woman with silver hair and a deep tan, walks slowly among our outspread towels and speaks into a headset, occasionally pausing to demonstrate a pose. Her whispers in the PA system sound like they’re coming to me through a conch shell held to my ear. She tells us to stand and guides us through a series of arm movements. We slide our hands up our spines and then hold them under our chins, arms pressed together out front of us like folded chicken wings. Finally, we do a large breast stroke through the air and start again. “Let’s do three just like that: up through the back, scoop, exhale… good.”

Only toward the end of the session do I learn from a neighbor that our instructor is Louise Francesca Kenny, mother of King Gizz’s multi-instrumentalist Ambrose (whose father, Broderick Smith, was an Australian musician of some renown). This is probably why, when we’re done, and after everyone stands and applauds for several minutes, a large crowd swarms her. People hug Louise and ask to take photos. They give her gifts — hair clips, leather bracelets, little plastic alligators. A woman with stringy brown hair carrying a tote bag gives her a squeeze and hands her a bolo tie in the form of eggshell-colored ceramic lungs. Louise puts it on, and although she is wearing dark sunglasses, I can tell from the way she says thank you that she has started to tear up.

When the crowd finally thins, Louise and I walk over to a large cottonwood, and after several more people come up and hug her, we sit down in the shade. In loose-fitting yoga pants and a cream-colored T-shirt, Louise is an encouragingly vigorous woman in her mid-sixties, with the earthy composure of someone who can stand on her head for an extended period of time. When I ask her if she ever does yoga with the band, she says, “Oh, I’m always getting Ambrose to give me a stretch.” Not often enough, though. Watching the aggressive pace of the band’s lifestyle at the festival has been slightly alarming. “People are at them the whole time, whether it’s the fans or people backstage, and then they have to perform, which is obviously what they’re here for,” she says. “You get depleted.”

For a while Louise tells me about Ambrose’s childhood, an origin story that will sound made up but is, in fact, true. She says that he developed an almost cartoonish passion for the blues as a boy, beginning with an infatuation with Elvis by the time he was three or four. When he discovered the Blues Brothers, she bought him a little suit and trilby hat to wear around. And when he learned about the black musicians that Elvis et al. were emulating, he became hooked on the source material. “We had this ghetto blaster, and he wouldn’t go to bed unless he had Sonny Boy Williamson playing or B.B. King or whatever,” Louise remembers.

As early as six, she says, Ambrose began playing his harmonica on the street, and at eight he released an EP of blues tunes. He would play so much that his lips cracked and bled. “This is without a word of a lie,” she says, holding her hand up as if taking an oath. “I’d have to confiscate the harmonica and put the cream on and make him have a break.”

I ask her how it feels to go from watching Ambrose at that age to being here, where thousands of people have gathered to hear his music. She pauses to consider. “I was so overwhelmed today with the reception I got, and that was all because of him, of course,” she says. “So, I guess seeing it on the internet is one thing, but now being here in the thick of it and feeling it firsthand is really just the most incredible experience for me.” As if summoned by these words, a barefoot woman with a cheerful, ruddy face interrupts us to thank Louise and hand her a plastic baggie with several daisies in it. As the woman walks away, Louise fishes one of the flowers out and tucks it behind her ear.

After two days of overcast weather, the strength of the sun is jarring. People have set up hammocks in the pine trees on the outer rim of the main stage area. In between acts, most of the crowd retreats under the trees or repairs to the well-shaded food vendors while somewhere a DJ plays pulsing electronic music at a low decibel. By the time Babe Rainbow gets on stage, the crowd has tripled. One of several Australian bands that came up through Flightless Records (the label founded by former King Gizz drummer Eric Moore), Babe Rainbow plays beach-bum psychedelia that, on their studio releases, is usually groovy and danceable. On stage now, however, they’re performing at a drowsy, zenned-out pace, lulling the crowd into a trance. Wearing red-tinted glasses and a maroon wizard’s robe, the lead singer is almost whispering into the microphone, shaking a tambourine in one hand and two maracas in the other.

All throughout their set, thousands of fans are funnelling into the main stage to position themselves for the last Gizz show: all of the fanatics in masks and cloaks, and packs of mustachioed men in matching jumpsuits, and couples holding their children’s hands, and an awful lot of dudes in dresses. Which, of course, comes with the territory at a music festival.

I’m standing next to three square-jawed fellas who look like they work in private equity and belong to a country club in Connecticut, if not for their matching floral-patterned skirts and tank tops. I tap the largest one on the shoulder and ask him politely if they’re dressed like this for any particular reason, or if they’re just experimenting or what. He looks at me with surprise. “It’s drag night,” he says. “There was a post about it on the band’s socials.”

And when King Gizz comes out, they too are all dolled up, wearing dresses and skirts and makeup. “Thanks for always turning up,” Stu says after half an hour of acoustic boogies. “Thanks for following us on all our crazy adventures.” Nearly ten thousand people roar as Joey, one of the band’s three guitarists, does a little bend and snap. Stu marks the hard transition to thrash with a rebel yell, and the crowd pivots with the band. We immediately throw our hands in the air and wiggle. A conga line of long-hairs passes me, heading for the mosh pit. I grab the shoulders of the caboose and follow him through the crowd.

The sea of nodding heads begins to get choppy as I approach the pit. I stand at the edge for a while and help maintain the border, surveying the onslaught before me. The lush grass has been churned into dust. People are bouncing off each other and flailing their limbs. They seem to be enjoying themselves? A short, stocky guy drenched in sweat comes up to a girl standing next to me and asks her if she’s doing okay. They pass a water bottle back and forth before he kisses her cheek and slips back into the crowd.

Here’s my moment: I get into an athletic stance, and follow him. Almost immediately, a scrawny boy in front of me falls flat on his back. I join a human fence that quickly surrounds him, yelling, “Whoa! Whoa!” to ward off errant moshers as we help him up. I then pinball past a bearded giant in a powdered wig and a full face of makeup who is windmilling his arms like a berserker. He is a chaos agent who does not seem to have my best interests at heart. I move far away from him.

Coming from the stage is the sound of cascading guitars while Michael Cavanaugh whacks the everloving shit out of his drum kit at full speed. Stu is now wearing three or four different hats that people have thrown onto the stage while he chants with Ambrose: “Dance beneath the moon’s bright glow / As charms they work to and fro.” After a few songs, I’m getting the hang of this moshing thing. All around me is a seething mass of smiling faces and elbows. I hop around, collide with people, and give and receive friendly shoves.

At the end of the set, the six members of King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard bow and thank everyone and hug each other and take a photo in front of the crowd. After playing nine hours of music in three days, they walk off the stage for good. Not unreasonably, there will be no encore. But we stay, thousands of us, hoping for more, chanting “Gizz-zard! GIZZ-ZARD!” over and over again, cheering with false hope even as the roadies begin to disassemble the band’s arrangement.

There are a few brief late-night sets, but most of us pack it in. In the slow march back to the campsites, I see Anthony, my camping neighbor and a seasoned King Gizz superfan, standing by the water filling station in a daze.

“Man, that table set?” he says, meaning the techno portion à la Nathan.

“That table set, wow,” I agree, and I tell him about my foray into the mosh pit. He slaps me five. As we watch the passing throng, I ask how it feels to have the twenty-first King Gizz-notch added to his groupie belt. He smiles and shakes his head. “I don’t know, man, pretty good,” he says, peering at me through his horn-rimmed glasses. “But I’ll tell you what, I’m already thinking about next year.”