Passengers

Crossing the Continental Divide in the hopes of finding Don

Don’t gamble in Reno, especially at lunchtime

We are all passengers here, abandoned to our singular devices

The howl of a train whistle instantly places me in the moonless bedroom of my childhood, its distant sob unlocking in me a loneliness I have no answer for. We are halfway to Iowa before I realize that I am, in fact, inside the sound that I am hearing. I am a passenger on the train.

We left Chicago at 2 this afternoon, slipping past the backs of countless gray shipping warehouses and through the late-September cornfields of central Illinois. You see people’s outdoor punching bags and above-ground pools, their fabulous collections of seemingly useless cars in their driveways and backyards. Sometimes they even come out and wave as you pass. Just after sunset in Ottumwa, Iowa, is when you get a chance to smoke. From there it’s all downhill until tomorrow.

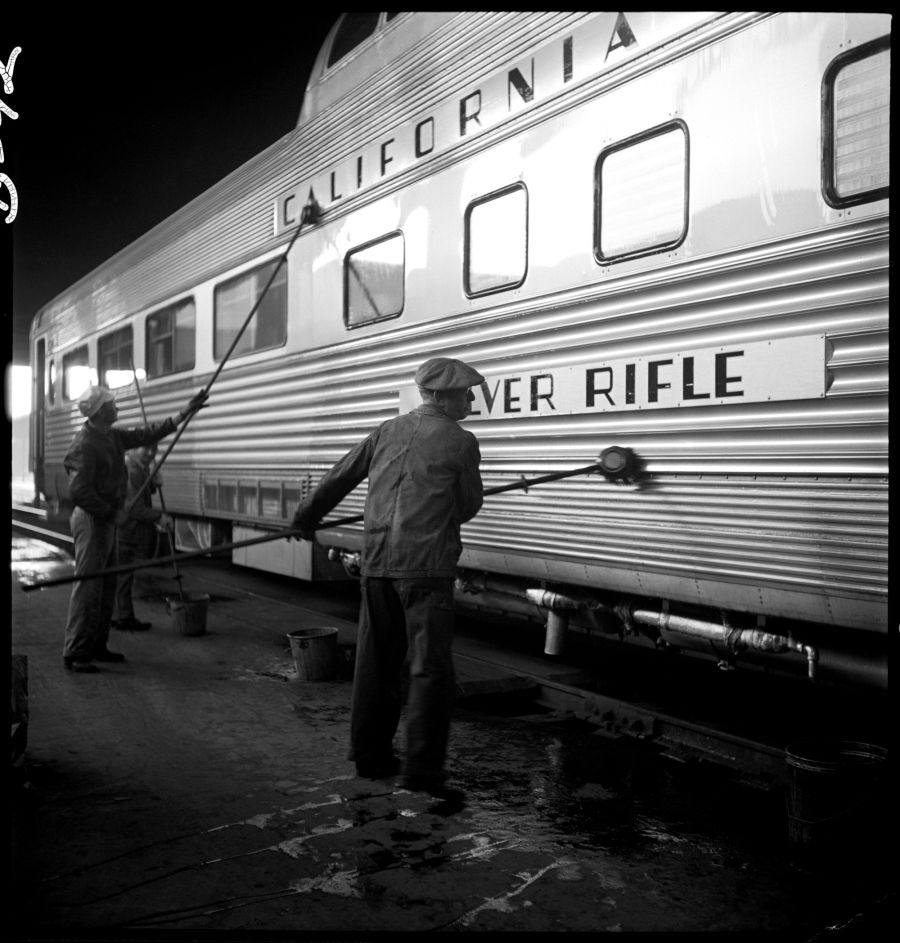

The California Zephyr is the second-longest train route in America, a 2,438-mile journey through the Great Plains and into the Rocky Mountains, along the Colorado River and past the Great Salt Lake, through the Great Basin Desert and into the Sierra Nevada by way of the Donner Pass, before reaching its terminus in the San Francisco Bay. To ride from one end (Chicago) to the other (Emeryville, California) takes just short of 52 hours.

Of the Zephyr’s two-level Superliner railcars, there are three sleepers, a dining car, a sight-seeing lounge, and two coach cars — the cheap seats — wherein, the train being sold-out, you effectively sleep beside a stranger.

My seatmate for Illinois and most of Iowa wages some kind of magical war on a clunky laptop computer. Two demons named “Lord Slug” and “Gamma 2” are communicating with him through a pair of giant headphones. He asks me to plug his charger into a nearby outlet; this is the extent of our neighborliness. “I’m looking for tough, powerful troops — with hidden potential!” declares one of the demons.

As there isn’t much to look at between Galesburg, Illinois, and Mt. Pleasant, Iowa, I soon move to the sight-seeing lounge, the communal space above the snack car where a giant red-faced cowboy is deep in conversation with a chatty Indian tourist. The subject is the butchering of animals on his ranch.

“1,000 pounds of meat from just one cow?” the wide-eyed tourist marvels. “How much does one cow weigh?” “About 1,500 pounds,” the cowboy replies. The questioning goes on: How much does one pound of beef cost? How much does one cow cost to raise? How long until a newborn calf is fully grown? (“1,500 pounds in one year?! How could it be?”) “And it takes 21 days for a chicken egg to hatch,” the cowboy explains. “What do chickens eat?” “Bugs, mostly.” The tourist is enthralled. “I am a vegetarian,” he states solemnly, shaking the cowboy’s hand. “I have never eaten meat in my life. Thank you for your time.”

I’d ridden the Zephyr start to finish once before. Recently disillusioned by a series of long train rides that were nothing like what “The Gambler” had led me to believe they’d be, I’d resigned myself to the idea that the American railway, much like everything else, had lost its edge. Nevertheless, on that first Zephyr journey, I’d settled in to ride the Superliner in its westbound entirety, armed with a bag of grapes and a few appropriate novels on the subject of “the West” as told by alcoholic boomers.

I recall my seatmate flashing his ticket ruefully, as if to apologize in advance for the next 26 hours of his company; he’d disembark the following day in Grand Junction, Colorado. Beyond that, he didn’t say much. He was older — hard face, white beard, strange pants — and as we hurtled through the void of western Illinois, he minded his business, I mine. Still, I couldn’t not notice the half-pint of Fireball slipping out from his backpack every 15 minutes. As for the impending reality of this man being my bedfellow — I kicked that can down the road.

After an hour, the man was ready to talk. He’d been living in the suburbs of Chicago for some time, but his ticket to Grand Junction was one-way. Years ago, he said, he’d owned a house in San Diego. “Feds took it,” he told me, “when they got my brother. They got him on charges of terrorism and tyranny. Two bodies in the house. Brother died in federal prison. Funny thing — he went to Harvard.”

“So did Ted Kaczynski,” I offered. The man then excused himself to the snack car, returning with two Stellas and a small bottle of white wine, which he handed to me. “Don’t know if this is what you like,” he said shyly. “I guessed.”

“I don’t mean to interrupt,” said a voice across the aisle, a rangy man of maybe 40 in a gray sweatsuit and cheap black shoes. At his feet, I remember, there was a flimsy mesh bag revealing a stack of books and papers and something pink that looked to be a set of dentures. “I wasn’t trying to eavesdrop,” he went on. “But I just got out of federal prison, actually.”

He’d left FCI Yazoo City in Mississippi the day prior, boarded the night train to Chicago, waited, changed trains, and was headed to a halfway house in Omaha, a place he’d never been. He had moved from prison to prison many times before, but this was his first day of anything like freedom in 14 years. (Manufacturing meth had been the ticket.) “That’s why I’m dressed like this,” he said. “I was afraid people would think I was homeless.”

“Well, I am homeless!” my seatmate hollered. “So you’re all good here!” He burst into a coughing laughter, which we joined. “Just so you don’t think I’m some asshole looking for sympathy,” said the man in gray, flashing his prison ID card. My seatmate countered with his shelter-issued homeless ID. I knew their names now: Chad and Don.

“Can I buy you a beer?” asked Don, my seatmate. “I wish,” said Chad. “Halfway house.” At the smoke stop in Ottumwa, we huddled in the day’s last light — Don and I smoking, Chad shivering, lost in thought. Back inside, Don quietly slipped Chad a twenty.

I bought Don a beer in thanks, he bought me one back, and so forth. I felt some guilt accepting $7.50 Stellas from a man I knew now to be homeless, but to deny his largesse would be worse. By sundown we were drunk. “I like to smoke a little weed — good weed, though. Like to do a little coke, too,” Don said. “Don’t smoke crack anymore. Probably won’t again.” He’d walked from Moab to Chicago “a couple times,” he told me, but that was off the table. “Banned from two states. Utah and Texas I’m not allowed, so if we’re going on holiday, we’re not going there.”

Don hated being homeless in Chicago; he was always having to pay off stupid young guys for protection. Grand Junction would be better, so he hoped. He liked to make wire jewelry, though someone had stolen his supplies, but maybe Colorado would appreciate his work more. Maybe he’d even rent a room there. “Finally got my documents together for my inheritance. Dad set up a trust before he died,” he said. “Took me a few years. Now I get ten thousand dollars every two weeks.”

“You get what?!”

“Yep.”

“Uhh... you should probably rent a room!”

Don laughed. “Just not used to it, I guess.” It was dark, and he was fading. His stories had started to repeat. “I guess I’ve been a bad boy most of my life,” he muttered, only half to me. “I’m 65, but I won’t be here much longer. How much more can you take?” He politely promised not to kill me in my sleep; then he was snoring. I must have followed not too far behind.

That was two years ago.

Tonight the train is quiet as we rumble through the dark, past towering grain silos like lighthouses on land, quiet save for the streaking howl of the occasional train whistle and the powerful snoring of the witch-faced woman behind me. The Zephyr’s timetable is engineered for thrills: It’s nearly midnight by the time you pass into Nebraska, so you sleep through the Great Plains, provided you can sleep at all. But to locate the sublime in a darkened tallgrass prairie bookended here and there by flour mills is what separates the real romantics from the wannabes. I watch it pass, forehead pressed against the window. Still, the thought that I might be the loneliest woman to ever live crosses my mind. The train is lovely during the day; at night it gets you.

“There’s a very interesting fiction book about a coal train run off the tracks in this same area we’re passing through,” announces Conductor Brad over the speakers. “Moffat Tunnel, which we’ll be entering shortly, is 6.2 miles long. Inside, we’ll cross the Continental Divide and reach 9,270 feet of elevation — the highest you can go on the entire Amtrak system — and the deepest, with more than 2,500 feet of solid granite above our heads. In the book I mentioned, the Yellowstone Caldera erupts while the Zephyr is inside this tunnel, leaving its passengers and crew as the region’s sole survivors. You’ll find this and many other stories in The Last Zephyr, available on Amazon.”

“That’s Brad’s book,” cracks the attendant passing through the aisle. “He thinks he’s slick.”

Amtrak’s long-haul employees are among God’s chosen people, blessed with charisma, diplomacy, endurance, and a wealth of knowledge on railroads and the land around them. The morning is getting on, and we’ve reached the most majestic portion of the journey: the fifty or so miles west of Denver, in which we’ll make our snaking climb up the Rockies’ Front Range, following the Colorado River through 1,300-foot canyons shaggy with pines and firs and shocked here and there by aspens so yellow they seemed to actually glow. “Keep your eyes open for mule deer, elk, bald eagles, pelicans, and some of the highest forms of human evolution — the high-altitude, cold-springs fisherman,” forewarns Conductor Brad.

I watch the blur of greens, yellows, and blues from the sightseeing lounge, where Amish families are playing dominos alongside European tourists who evidently feel enough at home to remove their socks and shoes. These wayfaring Euros are always tactically outfitted in fanny packs and performance fleeces, ready at any moment to be strapped into a zipline, yet constitutionally underprepared for the American railway experience: tweakers in Cookie Monster pajama pants cursing as they rifle through suitcases full of debris, urine-soaked restrooms, wild-eyed men in motorcycle leathers cracking beers at 6 AM. This is the train I love, aboard which anything can happen.

We pass a herd of mountain goats perched on the cliffs of Glenwood Canyon near a sign for a town called No Name (population 117). “Ladies and gentlemen,” announces Conductor Brad, “this morning I told you we were going through the first of 43 tunnels. Shortly, we will be going through the last. That’s the Beavertail Tunnel, and it will take us through Palisade — you may have tried their peaches, which are among the country’s best — and onward to Grand Junction.”

I know two things about Grand Junction: A friend had once gotten tattooed here by an artist who nodded off twice during the process; and, secondly, Don lives here, in a home or otherwise. That’s enough for me to decide to stop here for the night. “Junction, huh? You ever been here?” asks the attendant taking my ticket as the train slows to a halt. “It’s uhh, well… It’s alright. You’ll be alright.”

Grand Junction, the largest city in western Colorado, sits in the valley between the 20-million-year-old Uncompahgre Plateau and the mystical Grand Mesa, the world’s largest flat-topped mountain. The Utes called the mesa Thigunawat (“Home of Departed Spirits”), an apt setting for the wanderings of warriors past. Look eastward from the observation tower above the Museum of the West and you can just make out pale markings against the dark volcanic rock: the Thunderbird, who ruled the sky above the great plateau, according to Ute legend.

It’s said that two strange winds blow across the mesa’s crest: a Thunderbird and a Ute warrior, each calling for their child. The winds are calm today, but downstairs in the museum, a postcard scribbled in some kid’s handwriting is pinned to a display case: “THEYRS MORE IN THE WROLD THEN WHAT MEETS THE EIY EYEE.”

“I like people from Chicago. Y’all crazy,” says my Lyft driver as we cruise past several billboards hawking new sets of teeth. Her hair is purple; she’s recently divorced. Just the other week, she says, she hit a woman with a bat for talking smack. “Oooh, Scallywags!” she exclaims, pulling into the dive bar’s mostly empty parking lot. “Girl, I’m jealous.” Inside, a dozen men stare dazedly at the football game, comparing the respective failures of their various parlays. “I’ll bet on anything,” says a man nursing a hangover from last night. “I’d bet on Chinese women’s ping-pong if it happened to be on.”

I order a Coors Light and skim Scallywags’ crude menu. (Am I in the mood for the “Beat Your Meat” pizza, a “Cobb Gobbler” salad, or the half-pound of Rocky Mountain oysters known as “Cock and Balls”?) The cook, fresh off his shift, takes the barstool to my left. He’s 72 years old, though he doesn’t look it, with a deep and stoic voice that is distinctly Native — Osage, to be exact. Of the 38 states he’s lived in, his least favorite was Texas, where he’d always get pulled over on account of being mistaken for an illegal Mexican. On one such occasion, he had with him a small watermelon for a friend’s barbecue. “You call that a watermelon?” the cop had said. “I suppose in Texas you call that a grape,” he’d replied.

Down the bar, a harrowed man waves over the bartender: “Vodka... whatever... Red Bull... the biggest glass... a double... I can pay ya...”

A bar is like a train, all of us going nowhere together.

Beyond the river, where I’ll sleep, the sun is setting behind the purple mountains. A pair of Jehovah’s Witnesses are packing up a cardboard sign that wonders: “WILL SUFFERING EVER END?”

I am further now from 30 years old than I am from 40; in many ways, my life is better than it’s ever been. But there is something truant in me, something that wants to skip out. And though I would miss my sisters and my friends, I can picture myself leaving without saying goodbye. It’s not that I’d start over, I wouldn’t start at all — no moral compass, no allegiances, no plans. And every night in some strange bar, I’d fall in love with someone new.

The sleepiest place on earth is an Amtrak station in late afternoon. A series of yawns circle the airless Grand Junction station, from a pair of elderly couples to an emerald-haired goth to a man about my age dressed as Napoleon Dynamite. The only action in the room is coming from a wiry fellow deep in conversation with himself, until the building shakes as the Zephyr shudders and slows. “Group touch,” says a trio of pimply teens, here to bid farewell to their nervous fourth companion, and they tap their feet together as in some kind of John Hughes movie. My ticket is for Reno; we are headed westward still.

“I find it amazing that Utah exists,” says a Brit in tiny shorts with a cheerfully manic demeanor. He’s been hiking through the Southwest wilderness since June, and is only just reacclimating to human contact. I know just what he means, though — riding the train in Utah is like riding the train on the moon. Out from the craggy buttes and mesas of the 250-mile-long Book Cliffs crawl the shapes of ancient giants made of Cretaceous rocks. There seem to be no towns here, no human life at all, only now and then a coal train hurtling towards nowhere, past endless power line poles like rows of wooden crosses in the dusk.

“If you step out for a smoke at our stop at Reno Station, kindly put your cigarette all the way out,” says the conductor just ahead of 10 AM. “Otherwise it may start a fire that causes hours of delay. And by the way, that’s happened twice.”

Why I’ve chosen to spend the night in the Divorce Capital of the World is suddenly beyond me, as I drift from the station and into downtown Reno, a sorry tangle of casinos whose best years seem long past. The hot sidewalks are empty but for a few wild-eyed street-zombies, some of whom are having too much fun and others none at all. I slip inside the cheap and vaguely Spanish-themed casino where I’ve booked a room, and the day disintegrates in a puff of neon smoke.

Truth be told, I’m terrified of gambling. One must go all out in romance and let the chips fall where they may, of course, but when it comes to the possibility of losing $10 my instinct is to run. The noontime action at the Eldorado Casino offers little to persuade me otherwise: retirees draining their pensions into penny slot machines, red-eyed men with biceps sagging from leather biker vests, obese women leashed to portable oxygen machines in a dungeon choked with cigarettes and soundtracked by the relentless babble of video poker.

As previously mentioned in County Highway, I like to take my dinner in the afternoon; that way I can get to drinking, or go straight off to bed. Most of the customers inside Louis’ Basque Corner, where wooden blinds block out the daylight, are here to celebrate a 90th birthday: “Cin cin!” They toast with Picon punches, the bitter specialty of the house. “Do anything special for your birthday, Pop Pop?” a woman asks a trembling man. “Ate a ham sandwich and took a nap,” Pop Pop wheezes, turning back to the Wendy’s ad on TV.

At the waiter’s insistence, I join a couple in their seventies and their middle-aged daughter for a family-style Basque meal: French bread, an iceberg salad, beans with big hunks of chorizo, French fries, chicken thighs, a jug of wine, plus a round of Picon punch. The patriarch — once a warden for Nevada’s Department of Wildlife, now a photographer of nudes — has been coming to Louis’ since the ’70s, when Picon punches cost a nickel and the owner would pour wine into college students’ mouths from a leather bota bag. Forbidding me to walk the three blocks back to the casino, they kindly insist I accept a ride. I wait until their car disappears, then scuttle to the biker bar next door.

“I Shot the Sheriff” is playing as I duck into the grim cinderblock building next to a motorcycle repair shop. In front of every barstool is an ashtray and a video slot machine, and the glow of Austin Powers on the TV in the corner illuminates a sign that warns: “WE DON’T CALL 911!” A few black bikers in the colors of the Sin City Disciples sit stoically at the bar, while two security guards hit pool balls with their nightsticks. The bartender is wearing a nightgown, with her hair piled to the heavens. “Everything I know about being a woman, I learned from Dolly Parton, Zsa Zsa Gabor, and my dad,” she whispers while cracking me a Coors Light and urging me to take advantage of the leftover credits on the jukebox.

The fellow to my right singing along to “Tennessee Whiskey” left much to be desired, pitch-wise, but the energy was there. “I like to get drunk and sing. Hope you don’t mind,” he grins, baring a nonexistent row of front teeth. I now have a mission — to fill the jukebox with songs that he might like to sing. I watch for his reaction as Garth Brooks begins to play, until he happily belts: “Looong-neck bottle, let go of my hand!” We sang to Merle and Willie, Toby Keith and Kenny Chesney, and a little Counting Crows (“Mr. Jones”) just to keep him guessing, though he still knew almost every word.

Several hours pass this way, and the tequila shots keep coming. I relinquish my role as DJ when the howl of a mournful Stratocaster stops me in my tracks. “I played this one for you,” my toothless new friend winks. How did he know that “Wicked Game” is exactly the song I need to hear? I close my eyes and nearly levitate off the barstool as the music swirls around us in a cloud of cigarette smoke; then I slip out the door. Some moments are so good you have to leave before they end.

Back at the Eldorado, I funnel my last bills into the digital roulette table and bet it all on red. I sleep soundly, $43 richer.

A semitruck explodes on a highway in the desert, sending a thick pillar of black smoke into the clear blue sky. The European tourists press their cameras to the windows of the observation lounge, ooh-ing and aah-ing as 20-foot flames melt the cab and singe the trailer to ash.

“This is the best experience I’ve had in my whole life,” gushes an unshowered young man to his girlfriend on the phone. He’ll be on the train for most of the next four days, riding from Reno back to Syracuse to meet his lover in person for the first time. Perhaps he’ll stay with her forever. In the meantime, he wanders the cars, talking nervously to strangers. His ordinary life has become a grand adventure.

I’ve caught the Zephyr heading east to Omaha from Reno, which means two more nights aboard the train before disembarking at dawn. Coach seats on the Amtrak can be generously reclined, enough for a decent night of almost-comfortable sleep, provided no one sleeps beside you. Five days since leaving Union Station, it is my great, unlikely fortune to still be seated alone as newcomers stagger on from Elko or Salt Lake City. I hold my breath as an enormous woman lugs her portable CPAP machine slowly down the aisle, exhaling as she tumbles into the row behind me, nearly waking up her seatmate, a slumbering dwarf in tie-dye. I assume the fetal position and sleep through most of western Utah, jolting awake every few hours to see shockingly bright stars pierce through the window curtains.

“Today, ladies and gentlemen, you’re all in for a treat,” announces Conductor Brad, who I am glad to have as captain once again, for our journey back east. “The Colorado River is running clear and strong, and the aspens are just about as beautiful as I’ve ever seen them.” It is morning, and we’ll soon be crossing Utah back into Colorado. I order a burnt coffee from the downstairs snack car, whose microwaved cheeseburgers and styrofoam Cup O’ Noodles I’ve so far managed to avoid.

A long-haul journey on the Amtrak is not exactly chic, though from the outside looking in, we might appear to be celebrities. Whitewater rafters, fly fishermen, and passing cars along the highway routinely pause their business to take photos and wave at the great big iron horse that crosses the country once a day.

Of the half-dozen stragglers joining the car at Grand Junction, a white-haired fellow catches my eye. There’s something so familiar about the way the man is shyly hunched in a nearby seat, carrying no belongings. Conceivably, I might have seen him aboard a train sometime earlier this week — or could it be…? I’d barely gotten a glimpse of what Don looked like in the first place, two years ago, exchanging only a few sidelong glances for politeness’s sake. Might I somehow be seeing a flash of recognition when we catch each other’s eyes for a second across the aisle? Immediately bashful, I fumble over what to say. By the time I get my bearings, the man has disappeared.

“Ladies and gentlemen, 35 years ago an enterprising young conductor took the woman he loved to the foot of a waterfall in this very canyon,” Conductor Brad pronounces as we snaked through Glenwood Canyon, where the late September sunlight catches the river in such a way that it makes you want to die right there. “There he got down on one knee and asked for her hand in marriage. Well — she said no. She was looking for something else,” Conductor Brad went on. “They then had a very awkward hike back down the canyon, where he got in his car and drove home, and she… well, I’m not sure what she did.”

I scan the coach for the man who could be Don, but he’s nowhere to be seen. The car is loud and now nearly full with sweet old women dressed in thrift-store clothes, Indian men on passionate phone calls that somehow carry on long after the rest of us have lost service, and a dozen or so Amish, gently clucking their encrypted Dutch.

“Hey, maybe I want to be Amish. I think about it sometimes,” declares a man about my age, dressed in all black, like me, as two men sidle past in their straw hats and suspenders. Deliberating for a moment, they look him up and down. “You could be Amish,” one gallantly surmises.

I recognize the man in black for what he is — an agent of chaos — as he sucks his cigarette at the smoke stop in Winter Park, yelping to the mountains: “Sweet nectar of the gods!”

As is so often the case when it comes to chaos agents, I find myself beside him in the observation lounge, passing back and forth a bottle of red wine as we hurtle once again through the hell-black Moffat Tunnel. There’d been an incident in Rockford, Illinois — a fight over a woman, one that found him connecting a tire iron to another man’s face — which compelled Bonnie and Chaos Clyde to flee the state. “The guy’s alive, you know,” he unconvincingly assures me. “I’m not making you an accessory.”

The pair absconded westward in his beat-up old sedan, only for the vehicle to shit the bed in Colorado. The other problem, he tells me as we drain the wine, is that he has a girlfriend, and Bonnie isn’t her. “I like the bad girls,” he says, readjusting his fedora. The solution he’s arrived at is to leave Bonnie in Granby and sell the useless car for a ticket back to Illinois, where he’ll have hell to pay. “It’s like, I don’t go looking for trouble, but it always seems to find me,” he sighs as we descend towards Denver.

“Ladies and gentlemen, this is Lee, your steward from the dining car,” said a voice on the PA system. “Our esteemed conductor, Brad, has one trip left before he retires. I’m going to play a little song for him now, and when you see him, shake his hand — it’s only got three fingers, ’cause he cut the other two off trying to build a bench.” Through the tinny speakers comes the voice of Gladys Knight singing “Midnight Train to Georgia.” I bow to hide the tears suddenly streaking down my face.

He’s leaving the life

He’s come to know, ohh…

He said he’s going back to find

What’s left of his world,

The world he left behind not so long ago…

“I’ll tell you what, ladies and gentlemen — I have never seen a more beautiful day than today, the day you chose to ride the train through the Rocky Mountains,” said the now-familiarly disembodied voice of Conductor Brad. “Folks, this will be the last time you’ll see me as your conductor on the California Zephyr. But rest assured, I will see you again — the next time, as a passenger.”

Night was falling over the Eastern Plains of Colorado, and meanwhile I was developing a theory: Who you are is where you are. Tonight, along with Chaos Clyde and dear Conductor Brad, I was a streak of sound across the quiet prairie, somewhere in America in the dark.