Environmental Progress is Real

At least sometimes

Carbon-free electricity accounted for 97 percent of all new electricity-generating power plants added to the US grid in the first half of 2024

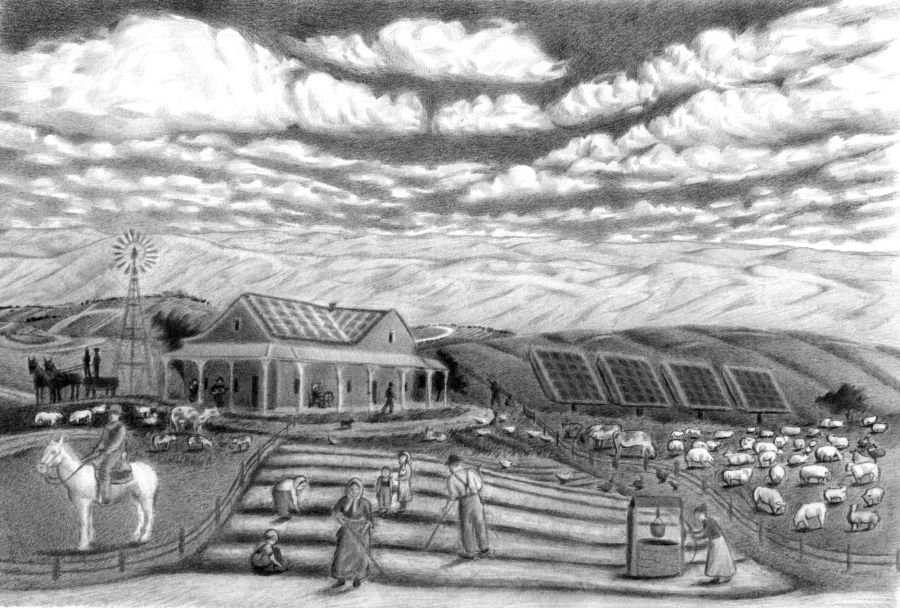

But will a future of mining pits, desert solar panels, and prairie wind farms be better than the alternative?

All models are wrong, but some models are useful, and the best models we have suggest that — assuming a modicum of continuing common sense and continuing ingenuity — the worst-case scenario for catastrophic man-made climate change is now firmly in the rearview mirror. Rapid innovation and production at scale have led to solar panels and batteries that cost a fraction of what they did five years ago. Paired with meaningful legislation and policy, like the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act in the United States, and with renewable energy standards in climates as diverse as North Carolina and Minnesota, deployment of green technologies is happening at a rate that previous “useful” models would blush at. For example, in the first half of 2024, carbon-free electricity accounted for 97 percent of all new electricity-generating power plants added to the US grid. Electric vehicle sales continue to experience double-digit growth year-over-year.

This success is visible in communities throughout the United States. In my small, rural community in California, more than one thousand housing units have been constructed in the last three years alone that do not combust fossil fuels on site. These buildings, ranging from single-family homes and granny units to large apartment complexes, have high-efficiency electric appliances paired with rooftop solar systems. As California’s grid gets cleaner and cleaner, these buildings will effectively be carbon neutral in their operations. Utility bills are expected to be about the same as they would have been with fossil-fuel powered appliances, and the buildings are cheaper and faster to build. Even better, the occupants aren’t exposed to harmful indoor air pollutants that come from gas combustion in furnaces, stoves, and ovens. Maybe best of all, these buildings haven’t added to the tangle of gas extraction, processing, transmission, and distribution lines, whose cumulative leaks may make natural gas as bad for the climate as coal. In 2024, the state’s wind, water, and solar electricity supply has so far exceeded statewide demand for more than 100 days.

This isn’t just a California success story; deep and meaningful climate-inspired energy reforms are creating healthier air, steadying the cost of living for low-income households, and increasing local economic investment across communities in every state in the country.

While progress has been steady, it is still true that most of the things I love in life depend on coal, oil, gas, and the petrochemicals derived from them. The fossil-fueled energy required to drive my daughter to basketball practice, heat the gym, keep the lights on, and freeze after-practice Otter Pops is immense. Not to mention the central role petrochemicals play in the hardwood floor’s coating, her basketball shoes, the dry-erase markers I use to draw up plays, or the cones we use for drills. I’m grateful for the luxuries afforded by the energy density and magic pliability of fossil fuels, I truly am. These benefits have undergirded most of our lives, but at a cost that we’re already experiencing and that we know can get a lot worse.

Things could have been different. We could have started transitioning to clean energy in earnest when the issue first hit the mainstream press in the 1950s. We could have pursued new avenues for powering the US industrial plants and individual homes after Exxon scientists forecasted the impacts of climate change in the late 1970s, or when the US Senate considered the issue in 1988, or with the end of the Cold War shortly thereafter. But we didn’t. Now the consensus approach to maintaining a habitable planet is to replace fossil-fuel generated electricity with renewable, carbon-free energy sources and transition fossil-fuel burning devices to those that run on this new, clean electricity. If we did so earlier, the transition we are facing could have been relatively painless. Instead, we’ve dug ourselves a much deeper carbon deficit and have a shorter period of time in which to pay it off.

Projections from the International Energy Agency suggest that by 2040 the demand for copper could more than double, while the demand for lithium could grow over 40 times. Similar stats exist for steel, cobalt, aluminum, and other metals necessary for all that clean energy and electrically powered equipment. That means extraction, which means a massive increase in land mining, and possibly sea mining as well. And what about all that new renewable energy I mentioned above? If you haven’t noticed them already, you can expect solar panels and wind turbines to soon be a common sight in landscapes and horizons across the United States. In the Western states alone, about one million Bureau of Land Management acres will need to be developed for utility-scale solar farms.

“A Clean Energy Future” has a nice ring to it, but you might ask, “Did we ever stop to consider the negative consequences?” Why would we actively support a future of mining pits, solar panels across the desert, wind farms across the horizon, human lives impacted, and natural resources degraded? How will the destructive thirst for capital adulterate the dream of an equitable and locally clean energy future? Can America build fast enough to even make this worry real? If so, how will we feel when faceless multinational corporations destroy scenic vistas in the name of the green transition?

In 1993, when the 49ers traded Joe Montana to Kansas City, my parents were shocked. We had lived in Reno for years, and one of my earliest memories is watching Montana lift the Lombardi at Super Bowl XXIII on a grainy cathode television. San Francisco was close enough to Reno to make them our home team, and Joe was a saint. My dad, watching the sports anchor convey the news about the Niners needing to make way for Steve Young, simply said, “I guess we’re Chiefs fans now.” With that, our various Sunday- and Monday-night viewing schedules were set for the next several years. I still remember my mom’s black, red, and yellow Starter jacket, the concrete curvature of Arrowhead Stadium, and Marty Schottenheimer’s glasses. It was Marty who taught me an important lesson about risk.

I must have been about 11-years-old watching a game with my dad, maybe Monday Night Football, when the Chiefs took a three-point lead into the last two minutes. Despite finding success with aggressive blitz schemes, Marty had them fall back into prevent defense. I asked my dad what he was doing. Why were they giving away eight yards at a time? Didn’t Marty see that preventing a big play was meaningless if it meant they could just march down the field? I knew the answer — being wholly obsessed with watching Joe and Marcus and Marty do their thing — and thought that showing off my football acumen with this comment might impress him. He knew I was right and honored my insight with a simple, “They’re losing the goddamn game.”

Setting aside the global catastrophe caused by accumulating carbon dioxide, methane, sulfates, and other particles in the atmosphere, the fossil-fuel economy is shockingly destructive. Concerned about the estimated bird deaths from wind farms? A study in the Journal of Integrative Environmental Sciences found that, on a per GWh basis, for every bird that dies from the life-cycle impacts of wind energy, over 34 die from the life-cycle impacts of fossil fuels. According to a study in Environmental Research from 2021, air pollution from fossil-fuel extraction and combustion was responsible for about 16 percent of all premature deaths worldwide in 2012, or approximately 8.7 million human deaths per year.

Concerned about all the mining needed for the metals as previously described? Me too; but you can at least take solace in knowing that in 2021, with coal alone, over 7.5 billion tons of material were extracted from the ground (with untold amounts of methane spewing out of the mines). And unlike coal, which you can only burn once, lithium is endlessly recyclable in increasingly efficient battery packs, providing the tantalizing prospect of a circular economy.

And what about those land-blanketing solar panels? Remember the one million acres of BLM land needed for utility-scale solar farms? That is real land, and I wish it could stay untouched. However, if we’re keeping a fair score, it’s important to note that 19 million acres of BLM land have active gas and oil leases as of 2022.

A clean energy transition will come with negative impacts. In nearly every aspect, however, these impacts pale in comparison to the harms currently being caused by fossil-fuel extraction, processing, transport, distribution, and combustion. Playing aggressive defense often leads to mistakes, but the alternative guarantees defeat.

Every state in the country has a public utility commission, or some equivalent. Public utility commissions regulate the roughly 165 for-profit investor-owned utilities (IOUs) that serve energy to about three-quarters of the nation’s utility customers. In California, as in most other states, these IOUs are granted a monopoly on providing energy to a service area in exchange for being closely regulated. The business model for these investor-owned utilities is relatively simple: They pass their operations and maintenance costs directly to their customers while also getting a guaranteed rate of return for every dollar they spend on infrastructure. If they convince their public utility commission that they need to build a power line and it costs them $100 in parts and labor, and if, say, they’re guaranteed a seven percent rate of return, they get $107 back, all of which gets billed to you and me. Now do the same math with a billion-dollar project and you can start to see where investor-owned utility incentives have the potential to be misaligned with that of the public good.

Discussions about public utility commissions and investor-owned utilities are esoteric (and usually boring), but they are also critically important to the story. I mention them here because the conflict between the fiduciary pressure of investor-owned utilities spending as much money as possible on capital projects and the public utility commissions’ roles in defending the public interest of delivering affordable, clean power will play a major part in shaping how the energy transition looks. And as noted in a 2023 study published in Energy Research & Social Science, this conflict is made more complicated by the fact that about a quarter of public utility commissioners in the US have previously worked in the industry they’re meant to regulate, and approximately half of all commissioners go on to work in the industry they have just regulated.

A major question persists: Will the green transition be derailed or delayed in favor of maintaining our reliance on the combustion of fossil fuels? Some have argued that the fossil-fuel industry is one of the greatest concentrations of power in human history. Power tends not to relinquish power and wealth simply because it is the right thing to do, and so it defends itself with a classic playbook. I remember when a voter initiative to ban new fracking and petroleum extraction was on our countywide ballot, Measure G. Walking to the bus after work one day, I saw Louisiana plates on a truck whose bed was full of “No on Measure G: Keep Gas Flowing” signs. I remember the mailers from fake groups like “Feel the Bern” and “Council of Concerned Women Voters” urging a no vote. These interloper-peddled signs and accompanying scare-tactic mailers were successful. $5,400,000 worth of Big Oil’s elbow grease (compared to the $78,000 in local funds raised by proponents of the initiative) meant the end of Measure G.

In the decimation of California’s redwood forest, as detailed by Greg King’s The Ghost Forest, I see the timber industry’s playbook being carried out on repeat by their fossil-fuel brethren. According to King’s book, the timber industry didn’t stop logging old-growth redwoods in Northern California after the first injunction was issued against them. Rather, they evolved and kept evolving, until 95 percent of that forest was gone, leaving denuded land and some beauty strips, which they sold to the public at a profit. So, it wasn’t surprising when the Sacramento Bee recently published an article implying that the nation’s largest natural gas utility used ratepayer funds to hire a law firm to quietly support a suit against local governments who were prohibiting natural gas infrastructure in new developments — a tactic that did, in fact, succeed.

Looking back 4.6 billion years, the earth has alternated between greenhouse and icehouse conditions nine times. Over those four-plus billion years, membranes, cells, and photosynthesis emerged, along with, more recently, homosapiens (200,000 years), language as we know it (50,000 years), and complex human culture (40,000 years).

When I was born, atmospheric carbon sat at 342 parts per million; today it is at 422 parts per million, an almost 30 percent increase in my lifetime. This exponential jump has no historic analogue across earth’s 4.6 billion years. In the decade I’ve been working on applied local climate solutions, we’ve seen unexpectedly rapid deployment of clean energy. But we’ve also seen growing headwinds, backsliding, and equally historic rates of fossil-fuel extraction.

Two weekends ago, I didn’t think about climate change once. I watched my daughter’s basketball game, got in a surf with my son, was lucky enough to spend time with my mom, and laid my head on my wife’s shoulder while I fell asleep. I wish that I could always live free from the realities of the world that is rapidly changing around us. But the particles in the sky continue to accumulate, and time’s verdict is always final.