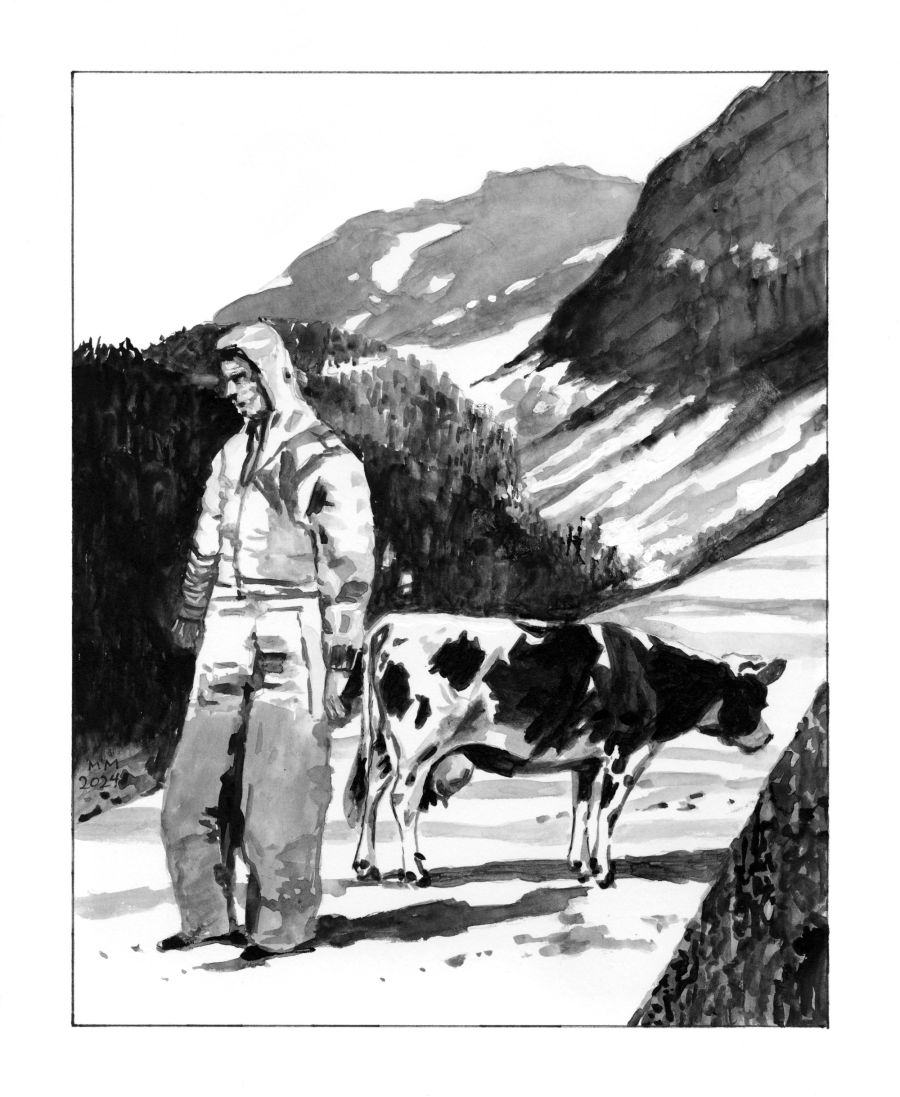

A Lone Figure

Alone in a black hoodie on the sparse and sometimes-deadly Mesa

Butch Tarko is a bad driver

Snoopy, Come Home

We were on the Mesa driving home when we saw a lone figure, dressed in black, walking up the road. From town to our house is about 20 miles — five miles over the mountain — on the only road that leads out here.

You pass the Continental Divide Trail on the left, but the road continues. The road is one and a half lanes. Off to one side is the edge of the canyon, dropping maybe two thousand feet; on the other side the cliff, also two thousand feet — only up.

The vegetation is a mix of juniper, prickly pear, cactus — anything with needles, points, or knife-edged blades for leaves, stickers, and sharp branches at eye level. Any plant is welcome as long as it can grow in nothing but rocky sand, with hardly any rain, at high altitude, and cause pain.

In other words, this is a region of the United States that is out to get you. Apart from the few Continental Divide hikers, there never appears to be anyone here, even though it is the Gila National Forest.

Not many drivers come out this way either. The road is honest in its homicidal nature. For entertainment, the cliff throws boulders and rocks at the passing vehicles with reasonably good aim. There’s no cell service for the next six miles.

The road climbs a couple thousand feet higher — 8,500 winding, unpaved, bumpy feet — alternating between where it has been scraped to bedrock by the county road department or is still buried many feet deep in clay mud that is treacherously slimy in snow or rain. When it dries it becomes a dirt cloud.

No mail gets delivered out here; no deliveries at all, other than propane, which comes in big trucks driven by modern-day brave men, the propane delivery guys, missing teeth or arms. Apart from them, the only people here are either residents or cattlemen running their herds on state land leases.

The cattlemen pay for that privilege, bringing their cows up in stock trailers and leaving them here until they are rounded up at the season’s end and taken to the feedlots. A lot of the land is too traumatizing for an ATV, so they use horses instead, trucking them up fully saddled in shaky stock trailers.

The only other visitors head to the Southwest Sufi Community for the weekly Whirling Dervish dance. There are only about 15 Sufis left in residence out here. They lost a lot of popularity after a Sufi leader got caught in some kind of pedophile activity a few years back in a game of Truth or Consequences.

The Mesa is around 35 miles long and 30 miles wide. On all sides, except for the mountain at the start, the plateau — basically a peninsula of elevated land — drops into the canyons, then the flat valleys. The valleys grow scrub grass that, from a distance, looks like amber waves of grain. (It’s not.)

Miles of self-propagating grama grass, low in protein and nutrients, sprout from the dirt like a man’s hair plugs struggling after a transplant. Past the hair transplant region is a mountain range, 10,000 feet high, devoid of anything except for occasional plumes of smoke, meaning a lightning strike has set off another forest fire. To get on the Mesa there’s only one way in; and one way out. We couldn’t figure out what the lone stranger in the black hoodie was doing.

There are a few aggressive drivers here who run people off the road. One is our neighbor Franz. Franz is 86, blind, and living in his converted workshop. The others up here (there are only 30 residents in total, spread out over the 30 by 35 miles of the Mesa) say it was Franz’s wife with dementia who caused the fire in their house about eight years ago. She had a habit of plugging in the electric coffee maker, then putting it on the stove over a low flame to speed up percolation. She had a Jaguar she drove in circles around the house before the main house burnt to the ground. The road would have wrecked that fancy a car.

Butch Tarko is also a bad driver. Butch Tarko lives down in a canyon on the left and grew up in a white Christian family compound, in the type of white family that prayed to a small brown Jewish Israeli man when they weren’t gathering munitions in case of marauders. They ended up in a gun battle with the FBI and became a TV documentary.

Now Butch Tarko lives here, in a nearly unreachable ranch. I saw him once. He’s a large man, 6’5’’ tall. He lost his cattle lease when he didn’t renew it. Somebody else bought it. It’s ten bucks per head of cattle per year — or as long as you want to keep them up here. No grazing lease is less than 70 acres per head. That’s how many acres it takes to starve one, slowly. Butch didn’t care. He still runs his cows, and the Gila State Land Cow Enforcement Division hasn’t done anything about it.

Butch’s cows are a particularly angry breed, and so is Butch. Before we moved here, there was a neighborhood committee meeting. The Dutch Sea Captain Piet (we bought our house from him after his heart attack); Franz, the 86-year-old blind neighbor; and the nearest neighbor on the other side, the local DA, decided the Mesa needed a private neighborhood defense force. But there was no money to hire one.

Out here, even the DA is not a rich person. He keeps a full-sized freezer next to his bed. No one knows why he needs a bedside freezer. We had seen the DA’s bedside freezer because he was trying to sell his house too, and a local realtor took us to see it. The freezer smelled strong.

The men — they were the authorities out here at the time — decided that Butch Tarko should head the neighborhood militia. His role was to Stop and Question Anybody Driving Up Here regarding their business. Butch was pleased to be made head of the militia. He extensively grilled anyone driving through, whether he knew them or not, pulling them over to the side for questioning, such as where Franz had hidden his collection of valuable coins. Everybody said Franz talked too much about his coin collection. A lot of things were missing after his house caught fire. Eventually the militia, led by Butch, with no one beneath him, was disbanded, although nobody living out here will ever tell you why.

You don’t need a permit to carry a concealed weapon in New Mexico, or anyway, in Silver City. I guess you don’t need a permit for unconcealed weapons either, since on almost every Walmart journey you can see one man or another dressed like Pancho Villa. A couple hours from here is where Villa invaded the United States in 1916. Like him, many Walmart shoppers carry a big gun in a holster and a bullet belt. Each bullet is in its own little loop, which is kind of neat, especially when you watch the shoppers, guns concealed or otherwise, trying to juggle a bunch of bottles of tequila and Malibu coconut rum because they forgot to grab a shopping cart.

Let’s say you manage on your way out here to get past the illegal shooting and drinking range on Bear Mountain Road and make it over the mountain to the flat part, to the Mesa. It levels off at about 6,500 feet, at which point you’re off the mountain and onto the clay road that goes on for fourteen miles. It was here we came upon the lone stranger in the black hoodie.

It was startling to see the lone figure, which is why my partner Robert slowed to open the window and ask him if he was okay. You don’t see anybody walking out here. The cows out here are easily able to access the road. They like to stand in the middle of it, and they are pretty aggressive. The angry cows on the leased state land have their babies with the angry bulls, who have big horns and are angry probably due to the cacti that get stuck in their manly dangling cow bits. There’s no water for them except the stream, far below, not easy to get to, that abuts the Southwest Sufi community.

The Sufis don’t like the cattle either. The only water they have is from the stream they use to wash in. They complain, having to bathe in cow-poopy water.

The stranger was a kid, looked to be in his twenties, dressed only in jeans and hoodie, clean cut, with pale baby skin. He might have been prepubescent, but he wasn’t. He was just weak in testosterone. He carried nothing. He didn’t have a backpack. No thermos. His outfit appeared to be too tight to conceal anything, let alone a weapon or a roll of toilet paper. He must have been walking for a long time, up the mountain and now halfway over the Mesa, in old-school Converse sneakers.

The days up here are hot. Some say being closer to the sun, at this altitude, makes it that way. Others say it’s government experiments. The kid wasn’t what you’d call equipped against the elements. “I’m okay,” he said.

“Where are you going?” Robert asked.

“Actually you could help me,” the kid said. “I saw on a map, if I keep going on this road it takes me over to Gila and then to Arizona.”

We looked at each other. “Well, no,” I said. “The road goes to the ranch at the end, which is private property. Then it’s blocked. It was a long time ago the Gila Forest Service blocked it at that point with giant boulders, due to people dumping garbage.”

“What kind of garbage?” the kid asked.

“Diapers,” we said in unison.

The kid shrugged, skeptical or indifferent.

“Do you want me to give you a ride to the point where the road ends?” Robert asked. “Maybe you can figure out a way to get around.”

My customary nervousness was refreshed. You don’t let a hitchhiker into your car, not out here. Even if he did find the back road to Gila and it was passable, it would be another fifteen miles from where he was at. The kid got into the backseat.

“You walked all this way?” I asked.

“I average about 20 miles a day,” the kid replied. He looked out the window.

We had just come from the supermarket. “Do you need something to eat?” I asked.

“What? Like, what?”

“What’s your name?”

“Cody.”

“Well, Cody, we don’t have anything already made or cooked, but we do have some fruit, some cheese.”

“Oh, I can’t eat fruit. Or vegetables,” Cody said. “Any fruit or vegetables goes right through. Greens, apples, carrots — if I eat it, in one end and out the other by morning, fully whole. Blueberries, beans, peas, corn — in the same state as when I ate it.”

There was a pause. “What do you eat?”

“If I buy a three-dollar pack of hotdogs and bread it lasts me a week. But I’m smart. I buy enriched bread. It has to be enriched. A man can travel for a whole day, on one hotdog and bread, if it’s enriched bread. That’s how I take care of myself. I make sure the bread is enriched.”

We thought about what he had said for some time. “You know it’s going to get cold tonight — into the low thirties. You don’t have other clothes?”

“No. That’s why I walk all night. To keep warm.”

He had been traveling, he said, for three years. He was 32 now, but when he moved to Las Vegas years before, he worked at a fast-food restaurant before finding a job at the front desk of a computer repair place. He didn’t know how to work a computer.

At first it was fine because he was just ringing up receipts for customers. He took it upon himself to learn about computers, but after a while he knew more than everyone else there, and no one could teach him anything further. And he was still the receptionist. So, he quit and went on the road.

He walked from Las Vegas through Arizona, which he didn’t like, and then on a route through lower Texas, which was even less pleasant. So he turned around to go through the bottom half of New Mexico. There were some good people on the road, and a lot more bad ones. The bad ones mostly had mental issues.

We passed our house. Robert is a big man, 6’4” tall, but I still hoped he wouldn’t invite Cody to stop at our place. One of Robert’s occupations, during his spare time, is to watch a lot of true-crime murder documentaries. After a show, he usually fills me in on the deaths of the poor women — garrote, drowning, torture, beheading with a machete — and how, after watching so many of these shows, he has figured out how to execute a murder and not get caught.

It’s just me and him out here. The isolation is extreme and the sun can be merciless, as well as the lightning, along with the tarantulas during mating season, generally August through October.

Robert recalls the true crime stories vividly, with passion, and perhaps this made me jumpier than I should have been. Even so, I didn’t want to invite Cody into our home, and by accident serve him some beans.

We had gotten to the turnoff for the local Southwest Sufi Community, down a steep cliff to the right. It was starting to get dark and the temperature was dropping. It would be another ten miles to where the road ends. If Cody did find the old road and could get through the blockade of used diapers, it was going to be another 20 miles on foot through the Gila Forest, where no one lived, over to Gila proper.

Gila wasn’t much of a town. We had driven there once. It had been the headquarters of the Lyons and Campbell Ranch, which in the 1880s accounted for about a million and a half acres. Angus Campbell was a prospector from Scotland, and Tom Lyons was some kind of a rich guy. Then something bad happened: Lyons shot his wife’s boyfriend and ended up marrying Angus Campbell’s wife, after Campbell died mysteriously in — I think — an Apache sweat lodge attack, after the Apaches got overheated. A few years went by and Tom Lyons also died, also mysteriously, due to being assassinated.

Today there is little left of the ranch, other than a sign explaining its history, cast in bronze, by the highway. The plaque is so lengthy it requires a dirt parking lot in front to stop to read the details. There’s not much else to do.

A million and a half acres is a lot, but there was nothing left of it now, and the town of Gila never amounted to much, either. There was a library and some kind of senior center — cinderblock, windowless. Even the gas station–convenience store had been boarded up.

To do any shopping, Gila’s residents drive an hour to our town, Silver City, where there’s a Walmart. Our Walmart attracts shoppers from an hour and a half away. The other Walmarts are even farther.

There remain a few regular homes in Gila. In one of those, 30 years ago a local couple stashed a de Kooning they’d robbed from the Arizona Museum. They disguised themselves, one in a wheelchair and the other — wearing a raincoat, sunglasses, and a headscarf — did the pushing. They sliced the de Kooning from the frame and rolled it up. Once home in Gila, it was nailed on the inside of the bedroom door as decoration, until they died and a nephew had an estate sale.

The de Kooning ended up in a local antique store. The owners generally traveled around and bought all the décor from hotels going out of business or in bankruptcy. The de Kooning went on the wall, still unframed and priced at $350. It was too much money for the area’s collectors. One of the owners collected Autumn Leaves-patterned dining services — he had complete place settings for 67.

Anyway, nobody said anything for about three years, at which point someone pointed out the similarities to this painting and the de Kooning that had been stolen 30 years before in Arizona, which was now valued at $30,000,000. The secondhand store returned it. We didn’t live here back then, though. I like to think I would have given the antique store $350 and kept my mouth shut.

Robert was on the same wavelength as me and didn’t invite Cody to come over. He drove on by, both of us neglecting to mention that the giant McDonald’s-style golden arch we had just passed — made of adobe — was the entrance to our home. The golden arch has a cast-iron mission bell hanging from it, covered with raven poop and clanging in the wind. If he didn’t know it was our entrance, Cody wouldn’t think we were inviting him to turn back and hunt us down.

“I’m worried,” I told Cody, “with the road being closed and the temperature dropping. You might want to head down to the Southwest Sufi Community.”

Robert pointed out the turnoff. “It’s about two miles down the road that way. They have cottages they rent for ten bucks a night, for spiritual people, and they probably would have some work for you to do there so you could refresh yourself for a couple of nights.”

We passed the road but Cody didn’t ask to be let out. “No,” Cody said. “I don’t want to go there. We’ve passed it now. I have a rule: I never go back.”

Robert stopped at a sign that said PRIVATE PROPERTY. We could go no further. Robert said, “Here, take a bottle of water. We always carry a case of water in the car. We have cheese and some bread. It’s a French baguette, though. Not enriched.”

“I’ll take the bread,” Cody said. “Not the cheese. Goes right through me.”

He got out, carrying the loaf of bread and the bottle of water. I didn’t see how he was going to make it over the mountain after dark, with lows below freezing. But he had said his father had been in the military, and they moved a lot to different bases, so maybe he had some survival skills.

It was a few days later that we heard about the murder in the Sufi community. It hadn’t happened all that recently, but two men, visitors to the place, had gotten into a fight over a female Sufi — one of the younger ones — in her 40s. She was actually of Greek origin, but anyway, she lived there, and one guy was going out with her, or thought he was; and the same with the other. They carried the fight away from the Whirling Dervish dance platform and into someone’s cabin — not the one where they were staying. In self-defense, they shot each other, leaving one dead. The one who lived was never caught. The Greek Sufi, unharmed, was another very fast driver on the Mesa.

I kept looking in the local news to see if a body had been found in the mountains between the Mesa and Gila, but I didn’t see anything. Maybe Cody had survived, or maybe I wasn’t looking for the right National Forest deaths listing.

If he didn’t make it, whether from foul play or hypothermia or dehydration or stepping on a hibernating rattlesnake or the hotdog diet, so far I haven’t found out. I wish I had gotten his number, but he didn’t have a phone and, as I say, cell phone service is patchy out here.