Lonesome Townes

Smoking, drinking, and eating saltines on the trail of a Texas music legend

‘He loved his life. He just couldn’t live it.’

Austin wasn’t always a crash pad for tech bros

I knew just how the motel would be: “groovy” in that Austin way; retro but millennial in schemes of pink and orange; perhaps a neon sign that spelled in cursive, “Y’all Means All!” or “In Willie We Trust.” Nevertheless, I’d found a room for half the going rate, and I’m hardly in the business of turning down a deal. Upon my near-midnight arrival, the lobby’s yawning concierge handed me a key of the sort that has the mailing address printed on the keychain, and written on the flip side: “SO CLOSE YET SO FAR OUT.”

“And will you need to park your vehicle?” she asked.

“Yes — well, it’s not mine,” I witnessed myself ramble from a mortified remove. “I’m kind of borrowing my ex’s car. I mean, it’s a long story.”

“Oh... ” said the young lady, unenthused. “I just need the license plate.”

Lying supine on the queen bed with my shoes on moments later, it struck me that it must’ve been a year since I was last in town. I always seem to make it just in time for Texas’ annual freeze, where unremarkable events in capable societies — temperatures in the 30s, or half an hour of icy rain — send the self-reliant cowboys into a total Dark Age meltdown. Last year at Charlie’s house, we’d lost power for five days, the first three of which we argued through, caving only on the fourth to book a Days Inn near the highway, where we at last declared a truce. But back home, the war resumed — over what I can’t recall, though I remember throwing mail. I zipped my cat into her airport bag, blocked his number in the Lyft, and said goodbye to Austin for good, or so I thought. Now here I was again, alone in a motel room where, from the jade glow of the pool outside the window, I could just make out the wallpaper: a collage of women’s lips in lusty poses (open, bitten, etc.) that inspired in me a dull, celibate mood.

For the duration of my flight to Texas, I’d looped two songs on repeat, which had left me feeling pleasantly disturbed. They were the last couple of songs on the 1971 Townes Van Zandt album Delta Momma Blues, named for a cough syrup that contained dextromethorphan, hence the “DM” on the bottle, which he nicknamed “Delta Momma.” First of the two was “Rake,” one of a few Townes songs I’d believe to be five centuries old if that’s what you told me, while reeling on the rim of some kind of ancient void. It speaks of days long past, cruel days fading into nightfall, wine, women, and guitars. “My body was sharp, the dark air clean, / And outrage my joyful companion,” he remembers, and goes on: “And time was like water, but I was the sea; / I wouldn’t have noticed it passing.”

I played it one more time and contemplated putting the roses Charlie’d brought me at the airport into water. Instead, I fell dreamlessly asleep.

I don’t remember when it was that I first heard a Townes Van Zandt song, but I can tell you how it felt. The room was dark, but even so I shut my eyes and sat up straight, how one might do should they be home alone and hear a window break. I can recall holding my breath for a verse or maybe longer, and meanwhile, Townes sang this:

My days, they are the highway kind

They only come to leave

But the leavin’ I don't mind

It’s the comin’ that I crave

Pour the sun upon the ground

Stand to throw a shadow

Watch it grow into a night

And fill the spinning sky.

There was nobody I knew in Chicago who listened to this music, or at least not at the tavern where I hung out every day. Then Jordan moved across the street: a welder from Montana with two monstrous sweetheart pit bulls whom he treated like his children. Jordan liked what I liked — which is to say, the blues — and for one demented summer we monopolized the jukebox, then retired to whichever was the evening’s chosen flophouse to scorch our nasal passages with bargain-bin cocaine and to play Townes songs — “Lungs,” “A Song For” — to which all you could say was, “Damn.”

I left Chicago with an unconsidered rashness that confounded even me — I’d met a long-haired piano player in a late-night bar, he’d invited me to Texas, and that’s all there was to that. By the time I returned, Jordan had stopped coming around. Sometimes I’d see him at the Starbucks, dogs sleeping at his feet, but not wanting to explain what I’d been doing the past year, I would wave and walk on by. When the bartender texts “call me,” it means someone has died, but with all the boomers in the place I never saw it coming. She said Jordan had hung himself in rehab. I didn’t know he’d gone to rehab, and that was the beginning of the things I didn’t know.

I checked out of the motel and fired up the LoveMobile, checking the flier for the church party, which began in 20 minutes. The morning’s incident had thrown me. In the dream Charlie recounted, I had been seduced by Townes, who’d then delivered him a song, completed but for the transcription. Townes himself insisted certain songs arrived in dreams, though not everything he said was exactly to be believed. Still, stranger things have happened. In any case, there went my love life, messing up my work again. Why’d Charlie have to go and make my Townes thing about him? Sobriety was my guess. Being freshly out of detox, as he’d been since New Year’s Day, can make a person grandiose.

The second-to-last pew of the Sweet Home Missionary seemed fitting for a lady in a hoodie such as I, though a scan of the small room revealed a casual affair as churchgoers filed in, hands full of homemade pie, shaking the floorboards as they passed. The pastor from before approached the lectern with a smile. “Let’s have some fun!” he whooped, adding, “But first, a word about pie — that is, peace… includes… everyone.” He welcomed to the stage a pair of shy fifth graders who traded lines from an Amanda Gorman poem, a test of cynicism that I passed. “I’m inclined to ask you to read it again,” the reverend beamed, “but we do have some musicians who are going to give us some traveling music. No need to leave your seats to do the traveling.”

From the altar, a small church band built the backbone of a song. Then, emerging from the pews, three silver-goateed gentlemen in suits: the Singing Preachers, who could’ve been the Stones the way the place erupted as they marched in place and harmonized, “Praise God, I’m going home!” I clapped and swayed and hollered, fully jacked up on the spirit, then slipped out before the final song. It was three hours to the Gulf Coast, and the day was getting on.

I’m quite a marvelous driver for a girl who got her driver’s license 15 days ago. That’s not to say I don’t have practice. I drove the LoveMobile all over Texas Hill Country, no problem: to the creek, the movies, or to pick up Charlie’s kid from the skate park Friday nights. We’d bought the car, a 98 Lexus with powerful A/C, from a dead lady’s estate sale out in Canyon Lake. “Let’s find you a treasure,” was the way that he had put it. They sold it to us for $450, supposing that it didn’t run.

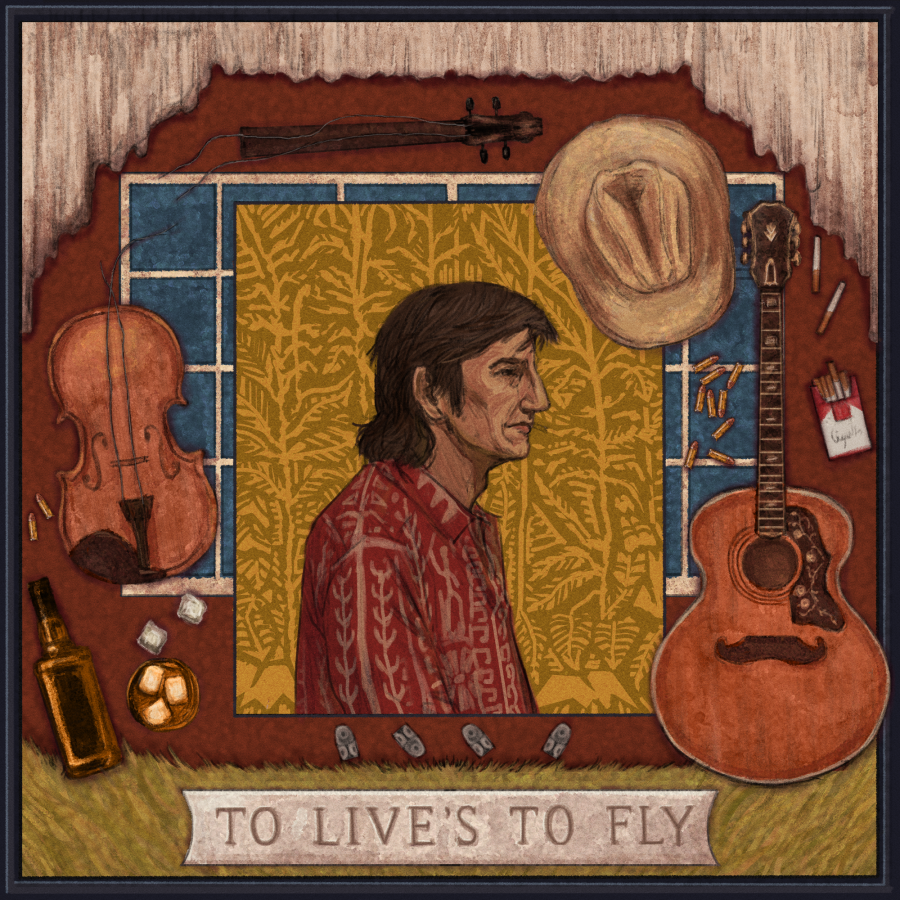

As far as Townes’ best album, the general consensus leans toward Live at the Old Quarter, Houston, Texas, released in 77 but recorded in 73. What passes for hits in Townes’ catalog are all within the setlist (“If I Needed You,” “To Live Is to Fly,” and of course “Pancho and Lefty” — though it was Willie and Merle’s cover that brought it to the charts) alongside odes to cosmic poker games, a bit of talking blues, and one of the scariest songs I myself have ever heard (namely, “Kathleen”). Ballads of pure despair are followed up by dirty jokes as if to say, “Isn’t that just the way it is?” At a Townes show in the 90s he might tumble off the stage, but at the Old Quarter in 73 you could hear a beer tab drop.

Wrecks Bell bought the Old Quarter in 1965, a dive in Houston’s wino district, for $1,300, just to be shut down two months later on account of some graffiti. “Back then we had these stucco walls and people could write anything they wanted,” he tells me by phone. He and Townes were the same age, and this year Wrecks will be 80. “The three they busted me on were, ‘Your local police are armed and dangerous,’ ‘Vandalize the church of your choice,’ and ‘Donald Duck is a Jew,”’ he cackles. “This cop would come in and erase ‘Jew,’ I’d put it back up, and he’d come back and arrest me. I was in jail, I dunno, ten times, then they just took my license away.”

The club had been closed a month when Wrecks drove by and saw it was for rent. “Then the Old Quarter started in earnest, and that’s when Townes would play.”

He’d met Townes in the green room of a nearby beatnik club that was notoriously dry; Townes had pulled a jug of wine tied to a rope up through the window. When the Old Quarter opened in 65, Townes was a local star. “When Townes walked in the room, he was in charge,” says Wrecks. “And not ’cause he was a bully. He’d walk in the room silently, sit in a chair, and was still the center of attention because he was a charismatic, tall, good-lookin’ genius of a guy.” By 73 the singer was by no means a household name, but on tour he’d fill 2,000-seaters, then give away the paycheck to Wrecks or some waitress.

The original Old Quarter closed in 79, but Wrecks reopened it in Galveston, an hour away from Houston on the Gulf Coast, in the spring of 96. Townes played the opening weekend, and then once more in October, three months before he died. The shows, says Wrecks, were awful. “But it didn’t matter. Townes would sell out a place, and they didn’t care if he was too drunk to play or not,” he tells me. “I read that people would come to see Hank Williams fall off the stage; they wanted to be there, and they’d pay for it. So of course it sold out instantly. It was still Townes.”

Wrecks retired after a stroke in 2016, selling the club to a local musician couple, but he still plays shows here and there. It’s plainly Townes’ legacy keeping the place alive, although Wrecks himself is an institution: besides Townes, he also played bass with Lightnin’ Hopkins and Lucinda Williams. He’s Townes’ subject in “Rex’s Blues,” a song he used to hate and now occasionally covers, which goes, “If it rained an ocean I’d drink it dry, / And lay me down dissatisfied.”

From the LoveMobile, the scenery takes a sharp turn toward the nautical, with Easter-colored beach houses scattering the swampy coastline between Galveston Island and the mainland. The Tetris outlines of offshore drilling rigs glow orange in early sundown as I park outside a motel butted up against the sea. The motel room’s walls are cinderblock, giving the space a certain institutional flair.

If someone had “gone to Galveston” around the 1950s, it meant they’d lost their marbles and were seeking psychiatric treatment. It was March of 64 when the Van Zandts drove their son, recently 20, to the Galveston State Psychopathic Hospital. They’d learned that Townes had withdrawn from college with a note he’d forged — and about his binge drinking and mood swings and long hitchhiking jags — and had shown up without notice to his Colorado flophouse, finding him stuck to the carpet after a night of sniffing glue. The doctors diagnosed him as an “obsessive-compulsive schizoid character with strong paranoid trends,” and prescribed a regimen of shock therapies over the course of three months, alternating electroshock treatments with insulin-induced comas. Townes returned to Houston with no memory of his childhood, a whole block of his life erased.

The sky bruises purple-into-black as I speed walk down the seawall, cold wind whipping at my hair. Bars with names like “The Poop Deck” bookend motels where silent cowboys lean into plastic chairs, tipping back Modelos and staring out at the black sea. The fried oysters of my dinner aren’t sitting as they should, so I attempt to chain-smoke my churning gut into submission. Out beyond the reeling neon of the Galveston Pleasure Pier, oil rigs haunt the dark horizon. The place gives me the fucking willies.

Too early for the Old Quarter, I weigh my drinking options and slip inside the bar that isn’t blaring “Piano Man.” The Texans have beat the Browns on the TV in the corner, which inspires a fan onscreen to do a kind of jumping jack headstand. The bar’s two patrons smoke indoors. I become the third. “You in the mood for something heavy?” one of them calls from the jukebox. “Heavy like your mom,” the bartender replies. A fourth chain-smoker arrives, donning a fedora.

“You from here?” I ask him later, lingering by the pool table. He slowly shakes his head.

“You don’t want to be from here,” he says gravely, then scratches on the eight-ball.

The Old Quarter is hidden in plain sight around the corner in a 110-year-old building. It’s nothing special from outside. Inside the drafty room, low-lit in neon violet, are seats for maybe 80 people, half of which are filled by quiet people drinking wine. A sheet over the window is painted in Townes’ giant likeness, while the wall’s remaining spaces are plastered with his ephemera: gig posters, painted fan art, an 80s photograph of Townes, Wrecks and Blaze Foley captioned “Wanted Dead or Alive.” I share a café table with a dapper older gentleman who’s been coming to the club’s annual “Townes wake” since it began on New Year’s Day of 98, where guests play songs by and for Townes for hours. One year, he says, Lucinda Williams came to perform “Drunken Angel,” which she’d written for Blaze Foley but could easily be for Townes. Tonight’s act is a Texas soul band fronted by a young man who sings almost like Al Green.

The last time Wrecks saw Townes was at his house in Bolivar, in October of 96. “I got him from the airport and he had his bottle of vodka. He was extremely addicted by that time, very ill and very weak,” he says. “Y’know, I have a theory that his taste buds were defective. Of all the stories you’ll hear about Townes, you will maybe never hear one around the dinner table. He didn’t care about eating. He could have $10,000, walk into a grocery store, and come out with bologna and white bread.” That day, three months before his death, Townes tripped in Wrecks’ yard. “We’re the same age, he’s three inches taller than me, and I caught him. He was light as a feather. I was able to just catch him like it was nothing.”

Back in Austin, I booked my third motel on the advice of Charles Portis (“I always try to get a room in a cheap motel with no restaurant that is near a better motel where I can eat and drink”) but the weather had hit the single digits, which meant the “better restaurants” were closed for the night. I cranked the heater and bit into the apple Charlie had bought for my return from Galveston, when I’d taken him for sushi to thank him for the use of what was technically my car. What had made us start to argue in the room an hour later? I couldn’t even recall, though it’d only been a day: something I’d said to the effect that it was, well, egomaniacal to bang on about how great he was after two weeks of sobriety, for which he’d labeled me an enemy of health and self-respect. “You are a deeply troubled woman!” were his last words from the hallway, just before I slammed the door. “You’re surrounded by disaster! There’s a reason you’re alone… !”

“Yeah, it’s called being an ARTIST?” I mutter to nobody, flinging clothes around the room. Outside my darkened window, I-35 is all but empty, and the owlish Frost Bank Tower glares at me to the west. “Aloneness is a state of being, whereas loneliness is a state of feeling. It’s like being broke and being poor,” Townes had said unsentimentally in Be Here to Love Me. “I feel aloneness all the time. Loneliness, I hardly ever feel during the day. But sometimes, like in motels… ”

“Alright, fuck this,” I exhale, pulling on my warmest layers and buttoning my coat. I knew one place would still be open.

The Texas Chili Parlor hasn’t changed since 1976, my new pal Jerry tells me from the next seat at the bar; he’s been coming here since then, so he would know. “We’d take that table in the corner, where you could do cocaine,” he says. After several rounds of magnums (rum with a splash of Coke), his friends unscrewed the chandelier, which came crashing on the table. “‘You frat bros, don’t come back here!’” Jerry recalls the screams. “I was offended. I’m not in a fraternity. We came back the next Friday.”

A folk club called Castle Creek, next door on Lavaca Street, shut down not long after the Chili Parlor opened. (Jerry’d been there, too.) Lightnin’ Hopkins and John Prine had played the venue’s early run. When a buddy of Jerry Jeff Walker’s asked to play for just five minutes, Jimmy Buffett made his ATX debut. In a scene in Be Here to Love Me, Townes buys the room a round of whiskey shots while onstage at Castle Creek, and I’d bet he made it next door for the cheap mezcal concoctions immortalized in Guy Clark’s “Dublin Blues,” a song Townes shakily covered in the year before his death: “I wish I was in Austin in the Chili Parlor bar / Drinkin’ Mad Dog margaritas and not caring where you are… ”

Jerry’s drink of choice is Deep Eddy Ruby Red and Topo Chico in about a nine-to-one ratio. “Watch this pour,” he whispers as Brendan, a Harry Dean Stanton look-alike whom Jerry calls “Brother B,” fills a tall glass with grapefruit vodka just below the rim, topping it off with two fingers of Topo Chico. “We call ’em Big Sexies,” Jerry tells me between swigs. “After three, you think you’re sexy.” This little number was his fourth.

Deep into my second, I’m distracted by the haughty elocution of a BBC narrator, profoundly out of sync amidst the local taxidermy. The voice belonged to a tall fellow, bright-eyed and robed in fur, a London-born philosophy professor at UT who proposed a change of scenery upon the Parlor’s last call: a politician’s speakeasy beneath the Texas Capitol. I followed down a hidden staircase to a room resembling a ship’s cabin, where the philosopher leaned closer, pressing me against the bar until a small bruise manifested on the low crook of my spine.

“So is it really true that Townes dug up Blaze Foley’s grave?” the Continental Club bartender asks — nothing else to do given that there’s no one else around, save for watching another Joy of Painting rerun. I stall with a sip of High Life, which accentuates my luncheon of saltines. “Depends what you mean by true.” The legend goes that after Blaze’s funeral, Townes exhumed the body to retrieve a pawnshop ticket for a guitar he’d lent his friend. Two hours prior, I’d knelt at the same grave.

You might call Townes the worst thing to happen to Blaze Foley; then again, take away Townes and there might be no Blaze at all. Everything that Townes was, the man born Michael Fuller ached to be: a blue-blooded Texan poet pulling songs out of the sky. Blaze had what Townes wanted, too: hillbilly roots embedded in the dirt. Mutual depravity intensified their bond, though that sells the friendship short. Fresh out of Austin State Hospital, where he’d checked himself in for detox before a gig in 83, Townes unraveled on the stage, butchering “If I Needed You” ’til Blaze appeared beside him, singing Townes’ words so he’d remember them again.

Live Oak Cemetery was empty when I’d driven there that morning and scanned the map for Section D, Plot 166. Finding Blaze’s grave turned out to be easy. It’s the one with all the empty Lone Stars littered among the paper flowers. The headstone marks the year, 1989, when Blaze was shot and killed at 40 at a house in Bouldin Creek. “I like to drink beer, hang out in the bars / Don’t like buses and I don’t like cars,” went the lyrics etched below. “Think I’m crazy, but that depends. / I don’t seem that crazy to me.” Beyond the fence, two dozen longhorns loitered the adjacent ranch. It didn’t seem that hard to sneak inside here with a shovel. Anything could happen, if you allowed it to.

The Continental Club opened its doors at 4 PM and I’d returned at 4:05, having resolved to drink my final day in Austin down the drain. I liked the Continental: a 69-year-old exception to the yuppie cowboy Main Street of South Congress, where hats, boots, and “provisions” are sold alongside salad chains, fitness boutiques, and lame Tex-Mex cantinas. Charlie’d brought me here a dozen times to watch the older couples twirl to Western swing, or other times, to watch him play. I liked being the girl who shook the cup around the room, panhandling so her troubadour could buy her something special, and had come to understand the role for what it was — the star. Now and then he’d play a Townes song, usually “Dollar Bill Blues,” to impress me in the way that he’d impressed women before, singing in that deep Old Testament voice I’d followed to Texas all those thousand years ago.

In 1992, a journalist asked Townes if he might benefit from country’s post–Garth Brooks mainstream appeal. “I don’t think, as a matter of fact, that I’m going to benefit from anything on this earth,” Townes replied. “There’s food, water, air, and love, right? And love is just basically heartbreak. Humans can’t live in the present like animals do,” he went on. “Humans are always thinking about the future or the past. So it’s a veil of tears, man. And I don’t know anything that’s going to benefit me except more love. I just need an overwhelming amount of love. And a nap. Mostly a nap.”

More love! This from the man I’ve been chasing around Texas, 27 long years dead, from whom grown men proudly pilfer inspiration in their dreams. Was it that the love was cheap if you could find it anywhere? Or a foil to turn away from, and toward the fact of your aloneness? “What can you leave behind / When you’re flying lightning fast and all alone?” he asks on “High, Low and in Between.” Then he answers his own question: “Only a trace, my friend, / Spirit of motion born and direction grown... And if a shadow don’t seem much company / Well, who said it would be?”

How could a man indifferent to existing write these words? I’d asked Wrecks on the phone. “He did love his life,” Wrecks said. “He just couldn’t live it.”

“You’ve been to the Hotel Van Zandt, right?” Jerry had asked me at the Chili Parlor, regaling me with photographs of his son’s recent wedding, whose reception had been held at the 16-floor hotel named for Isaac Van Zandt and his great-great-great-grandson. The place has a whole spiel on how Townes inspired the design: “industrial chic” meets “urban cowboy,” hung with trombone chandeliers and art by Townes’ eldest son, such as the portrait of his dad and Uncle Seymour in the lobby. The $246 million property squats over Rainey Street, the stretch along the river where single-family bungalows have given way to high-rise condos and the bachelor party bars I used to dread when Charlie played.

I ride the golden elevator to a restaurant named Geraldine’s, after Townes’ dog, where vaulted ceilings strung with Edison bulbs gesture towards the idea of backyard barbecue. It’s “the place to experience Austin’s diverse and eclectic music scene” seven nights a week, as per their website. The dozen or so men around the bar are dressed in start-up drag: cropped khakis and button-downs accessorized with tricked-out fleece, as if they’re prepared to leave the workspace and get strapped into a zipline. The women are uniformly blonde and drink sauvignon blanc; it’s unclear whether the merry bunch are couples grown apart or coworkers who’d like to fuck. I order a Vieux Carré as unfathomable strains of conversation pass me by: “Saw you getting your steps in, buddy!” “So it’s, like, technically an LLC. So smart!” “Tomorrow I need Terry to be quiet on this call… ”

What was I doing here? I paid the tab as the man beside me prattled to a colleague he’d like to fuck: “Third Eye Blind and Yellowcard? Not a show I’m gonna see. I mean, how many times have I seen Yellowcard?” By now, the Texas Chili Parlor was closed. I could go back to the motel, though I was certain I would not. I lit a match and smoked a while outside of the Van Zandt, watching a fellow in a cowboy hat blur past on an electric scooter. What I needed from the night was love in an overwhelming dosage, and to be left alone forever. I sent a text and disappeared inside a song:

There is the highway, and the homemade loving kind —

The highway’s mine.