The Death of a Horse

Hooves like walnuts

How the hell did we get here?

I envision a golden thread from my skull down to the earth’s core

“Everything you do now, makes a difference later,” David instructs me, looking down the barrel of another Bud Light. I walk Paloma into the yard. Her warm cheek presses against my knuckles. I pat her neck.

David pops open another can and stands akimbo, watching over the ranch. I feel a connection to Paloma at one moment, but then she bites my shirt. Her large, yellowing eye dilates in fright. I pull away.

“Are you sure it’s good to go?”

“Yes… ”

“Check the saddle.”

I check the saddle. One of the pad’s edges was improperly tucked under the stirrup.

“Was there a mistake?”

“No,” I lie, stepping back to Paloma. She kicks the ground a few times as David ruminates on new legal efforts to curb lead contamination from a nearby battery smelter. He references the cumulative impacts from the 60 and 605 freeways, as well as the City of Industry broadly. I breathe in the dust, trying to ignore the probable selenium bath in my lungs.

“Groundwork,” David announces. “Everything you do in preparation matters. Establish a rapport and establish a clear line of communication.” I promptly step away from Paloma, a somewhat sedate creature who loves a good sprint with the right rider, holding the rope in my left hand while guiding her with my right, curling it up to pantomime a snake. Paloma trots in a circle. I position myself behind her with my snake, and make exaggerated kissing noises to get her moving faster. Instead, she slows.

“You have to establish control,” he advises.

I try my hand again. As she runs, picking up speed in a clockwise rotation, David talks more about our organizing work together, how to mobilize against the creeping industrialism, how to defend this special space, to preserve the heritage that existed before LA’s suburban swell leveled everything in its wake.

I’m dizzy. My legs and arms tire as Paloma kicks out and runs faster. I give her more slack. But really, if Paloma wanted to, she could book it down the street with me tethered behind her like bait.

“The picadero gives an opportunity for it to have an opinion… ”

David always calls horses it. It gives me pause every time.

“The picadillo?”

“Picadero.”

“What’s a picadillo?”

“Picadero is what we’re doing.”

I keep spinning at the axis, highly unstable. The gravity, it’s the pressure of all this momentum coming undone with the slightest fault or folly. My footprints enmesh Paloma’s. Dust all around me, everything blurs.

“Now,” David yells.

I stomp my foot, pull the rope, and yell, “Woah!”

Paloma advances towards me, presses her snout to my chest. I press my head to hers, close my eyes. Our hearts are pounding.

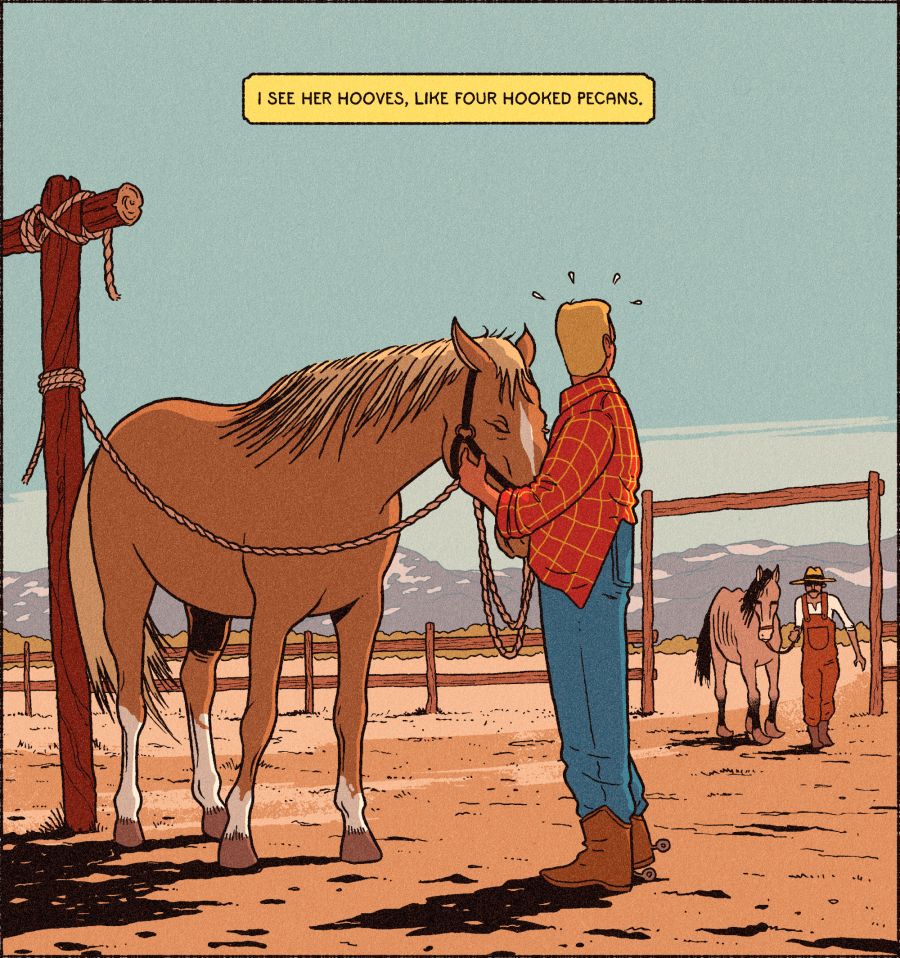

Meanwhile, the squeal of a metal gate. Ricky, the tio, is escorting a horse, an Azteca maybe. She’s limping, heavily. Walking over, I see her hooves, like four hooked pecans.

The other seven horses panic, screeching and kicking in their stalls, as the injured one overreacts, almost falling to the ground from the pain. She’s eventually tied to a pen where a colt is kept. I place two plies of alfalfa on the dirt for her as David and Ricky discuss what to do.

Apparently, Ricky just brought her back from Bakersfield where she was rescued from a family that had neglected her for almost two months. As David continues to work Paloma in a circle, I stand beside the new horse. The neighboring colt, Estalla, observes her and then nuzzles the rescued horse. Leaning onto the fence, we share eye contact, both wondering how the hell we got here.

My windows are down and clothing the San Gabriel Mountains are incredible arrangements of wildflowers. Rare super blooms are profuse in California this spring, enriching the setting with vibrant clusters, due to unprecedented rainfall. History pollinates a desolate mind in these moments with botanicals long past. Thousands of little ghosts are blossoming from these hills to tell of a world before.

And yet, I feel I should be transported to the Central Valley, sometime in high school, where I’m rolling a joint, watching the freckled hillside of cows, talking about bullshit like Charles Mingus or if Jack in the Box tacos are really vegan with some old friends that are probably dressed even more absurdly than I am in these corduroy pants, a linen shirt, and a bucket hat. A tear streams down my cheek as the dusk lights the walnut orchards with a cosmic fire to the tune of “Stella Blue.” There’s always that sense we don’t belong here. I still see the sign there on the barbed wire fencing: No Trespassing.

As I near Claremont, the wildflowers don’t invoke anything profound in me. I wonder if this is the trade-off for the happy pill. I wonder if I will ever again feel the intensity of seeing a wildflower, the comfort of a hug, the taste of a berry. Is it worth it? I just needed a break. That’s the bargain, eh? The Devil’s joinder… this synthetic, I opted to introduce in my body, to mitigate the depletions born into me, inherited, as anthropologist Claudio Lomnitz wrote, from a matrix of past decisions.

I watch the sea of flowers undulate on the hill, I want to shove them in my nose, to strip and spin them, just to feel something, to be, as they hype: here and now.

Dusk, and the tension bunkered in my shoulders is gone. I smell the spice of pepper trees taxiing on a nautical wind. Really, it shouldn’t be there; neither should I be here. But it’s a salve, soothing the aching in my chest that oscillates these days like driftwood on a spume. It’s all a mystery to me. Suddenly though, the inner turbulence subsides. Tranquility perches in my neck like an old bird before it passes on, leaving me to wonder.

I adjust my feet in the stirrup and pat Paloma on the neck. Her blond hair ripples and left ear twitches. The rank perfume of horse sweat on the sleeve of my sweater unlocks something earthen in me. Dust lines my nostrils. Maybe enough rough odors will break me through the other side.

My left hand grips the reins. Right hand on hip Charrería style. Fingernails, dirty, from digging in roots. I think of all the complaints I got working at Macy’s, Red Wing, and Olive Garden in my youth. The only job that accepted my body and what it produces was the apiary in Davis. The fuzz orb of a thousand bees purring above my head. I smell a fetid scent of burning sugar baked in the blaze of valley heat, as the herons stalk about their dead. And yet, it feels good: the mess of it. It feels good to be a monster, fermenting in the margins of space and time.

David rides Chulo ahead of me. Chulo’s agitated. His head bobs up and down in erratic motions. There’s a perceptible stress in his eyes. To our right, the steam of converted methane billows from the gas-to-energy facility on the shuttered La Puente landfill. It billows between a bouquet of eucalyptus trees. A powerline purrs.

I know a look of panic. I’ve seen it in the rearview mirror, bolting toward Claremont on the 210. Chulo glares at me and then Paloma. She moves faster. I don’t know if it’s to rank herself or motivated by a maternal drive. David has me watch Chulo’s hind limbs. I look for any clue of injury. But his aching, I can only interpret. We cannot identify his pain.

We are on a trail beside the La Puente Creek. Two geese are snacking on a salad of algae — a trace of a seasonal stream that flourished in this channel just last month. This vein taps right into the City of Industry, flowing through a Superfund site or three. As the temperature cranks, cooking this heat island of the San Gabriel Valley, this creek will symbolize the hollowed chute of a pistol, laying down what’s natural, to rest beneath the tombstone of Whittier Narrows Dam.

Otherwise, it’s quiet. There’s the sibilance of creeping wild rye, the trill of a mockingbird. I try to listen deeply. But I think I may be illiterate. There’s that familiar scratch of an oak tree. There’s the lisp of a warbler.

Starting at the age of six, I could be out in the grass alone for hours. I’d sit beside the creek running past my childhood home. Tadpoles swirling in the eddies, with half-formed legs emerging from their teardrop bodies. The guttural call of our neighbor’s cattle. Under the shade of valley oaks, the sea of grasses, up to my waist, would sway.

For years, day after day, I witnessed the conversion of fields to residential housing from the creek banks. It was the dawning of a new California, driven by a tech boom. Seeing ancient oak lands and native grasslands paved and developed. The songbirds faded over time. Cats that once strayed into our garage no longer appeared. The moan and tear of the bulldozers, the pounding of hammers, and the pouring of cement crescendoed in the distance. Emerging from the grasses were supermarkets, identical parks, intersecting streets, wires, tumbling trees, and pesticide fans.

It all happened after I was in the front yard one day, trying out the form of some monstrous Cthulhu offspring. Mom yelled from the window to quit. I was disturbing the neighbors. So I hid myself in the fields, with my tongue lashing, entirely uncultured, arms tucked and teeth baring, skulking around under an elm when a coyote appeared down the street. We locked eyes, the coyote and I. I’m not sure I’ve stopped looking.

David tells me to keep good posture and to communicate through my body, my pointer finger, and light pressure from the rein. I envision a golden thread from my skull down to the earth’s core. I kick my heels and Chulo begins his trot. My heartbeat slows.

“We know they have the power, that they could literally kill us if they wanted. But everything we did — the groundwork, and our preparation — has established control,” David explains, standing next to the air monitor. I’m riding bareback for the first time. After a moment of panic and fear, I try to remind myself that horses can perceive the subtlest subtext in the rider. Because they are prey, they have an incredible capability to read other creatures. I can smell my anxiety. I know Chulo can too.

I steer Chulo counterclockwise and he bobs his head up and down. I tug on the reins and try to calm him. My thighs press against him and I feel the tension along my back, within the arches of my feet. I look for David but he’s still out of view. Chulo starts to trot a bit quicker and I pull back on the reins a bit more. Chulo then starts to back up, turns, and trots toward the stable. He kicks out his back legs, I pull on the reins, and yell out “Woah!” He doesn’t listen. My head is inches away from the metal bar of the stable. Chulo won’t calm down.

In my panic, I calm down, ease up on the reins. Chulo stops kicking, I pet him on the neck, steer him back to the yard, and yield. We stand in silence together. There, like a herd of lethargic sheep moving pastures, purple clouds stray toward the San Gabriels. A car revs, and peels out a block or two down the way.

I’m smelling, looking like a monster, on the sweating horse. But ultimately, I believe it will all be defined in the end by how I land.

Over four to five days, I’d contacted everyone from the veterinarians to the sanitation district to find out how to euthanize and dispose of a horse for Ricky. I pretended he was my uncle, and we couldn’t afford to euthanize and dispose of the horse. The responses varied, from public facilities willing to “look the other way” while we trucked a horse carcass into a dump, to a concerned veterinarian who didn’t believe that the horse had to be put down. She became suspicious when I didn’t know the horse’s name. I texted Ricky for the name. He said to make one up.

That day, after finally finding a cheap service, I pull up to the ranch and walk into the yard where David’s looking at a rooster who, for the last month, refused to enter its cage. He nods and hands me a juice. I follow him as we walk toward the stable. Two days prior, in a rare summer LA “hurricane,” the rescue horse was tied up to the pen, under the shelter of the stable. There she remains chewing on a wheelbarrow of fresh alfalfa. She adjusts her knobby pecan hooves every other second. I can’t imagine the pain.

Ricky calls to tell me everything is in order and that a veterinarian will be there soon. I pet the rescue horse on the cheek and press my forehead to hers. I ask who could fuck this up so much. It became clear that the horse was given to the ranch in order for the previous family to avoid these euthanasia charges. Ricky tells me that when he went to retrieve the horse in Bakersfield, it belonged to a young boy. The boy was allowed to spend the night with the horse one last time before she was taken away.

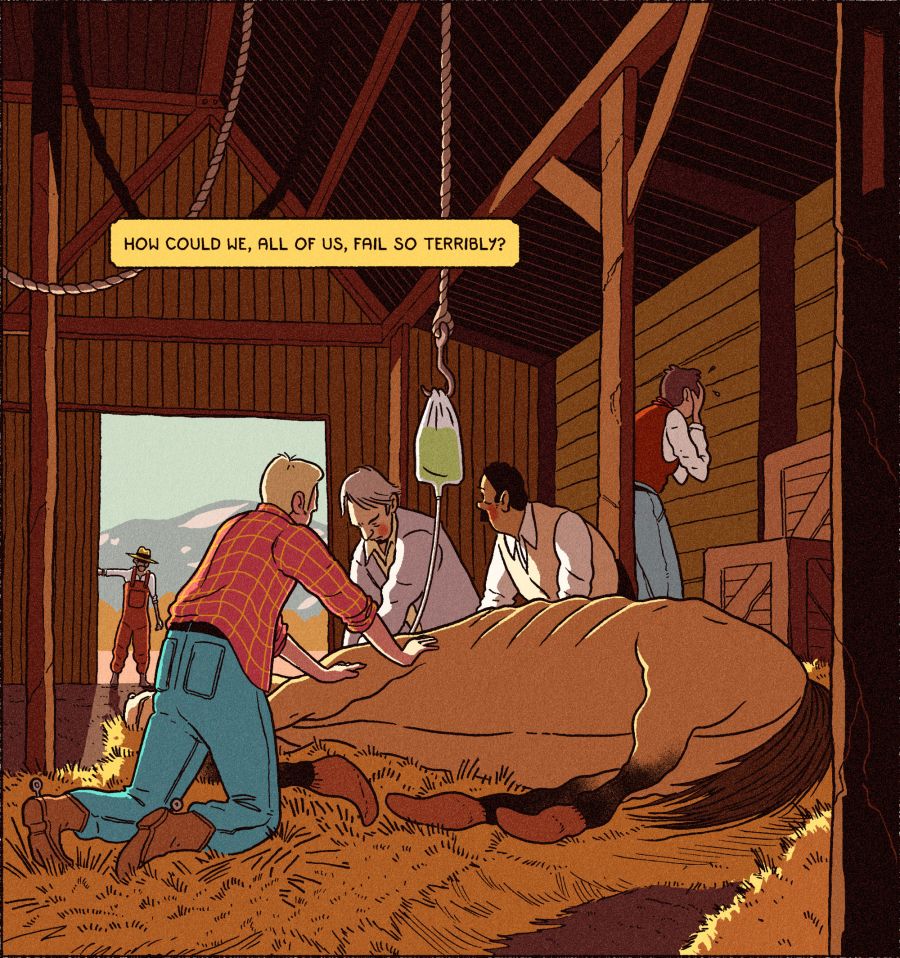

The vets drive onto the property and park beside the horse, opening up the bed of their truck, to remove a few kits. They shake our hands and prepare the euthanasia equipment, speaking in Spanish to David. They are solemn, I believe out of respect, but comfortingly confident in their assignment. One takes a large syringe and draws out cinchocaine hydrochloride for anesthesia. The rescue horse is trembling, so I try to calm her by petting her cheeks and neck.

After the anesthetic is administered, the vets grab her by her neck and tail as she stumbles like a drunk before collapsing to the dirt, almost smashing her head against the stable wall. I kneel down to caress her cheek, as she lays there with her tongue hanging out and chest moving slower and slower. I clean the tears leaking down her face and hum as the vet cuts a small slit in her neck, drapes a bag of potassium chloride from a rope hook, and places the tube in her veins. For about 15 minutes the green liquid empties from the bag into her.

I look into her large, beautiful blue eye: its spellbinding ecosystem, with all its stunning articulations, its layers and dimensions, and its softest shimmer of pulsing light. How could we, all of us, fail so terribly?

Slowly, she stops breathing as life departs. As the disposal truck carries her away, David cries and I hug him, patting him on the shoulder.