Lithium

Meet the human price of ‘environmentally friendly’ electric car batteries

We’ll put a 500-foot-deep pit in your barn

45-day supply of bottled water if your well goes dry

Corporate mining giant Piedmont Lithium Inc. fails to meet Chad Brown’s definition of a good neighbor

In the summer of 1991, I was five years old and living in my grandfather’s American dream. Together with my mother, we spent the warm season in China Grove, a farm town 35 miles northeast of Charlotte, North Carolina, fixing up a white one-bedroom house with a red-brick porch and a Rose of Sharon bush out front. For my grandfather, it was a homecoming. He was raised in the old white farmhouse, and when he married my grandmother — “that little hillbilly,” he’d called her, before their love blossomed — he tried for a while to make a home with her in a back building she insulated with newspaper clippings advertising farm-supply stores and White Lily flour. When The Great War was over, he came back to her and their new daughter in Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains. For half a century, he dreamed about the fertile North Carolina soil. He always thought he’d make it back there for good, but he never did.

Besides all the Bojangles butter biscuits we ate that summer, my most vivid memories are of our neighbors, Juanita and Miss Jolly. My grandfather had known these women for a lifetime — he’d grown up with them, gone to school with them, and his own family had shared their joys and sorrows.

By the time I came along, they were in their golden years, both widowed, and both happy to have the company of a little girl. Juanita was a mystery to me — a true southern lady. She tended to her house diligently, had her hair done every week, and gasped with delight at jewelry I made with moss and wildflowers and buttons I found in the dirt. Miss Jolly was a stricter sort, exacting. Still, she let me keep tadpoles in barrels behind her house and brought me red Solo cups filled with muscadines from her late husband’s vines. When I think about the kind of woman I want to be, the kind of neighbor I want to be, I think about these women.

Some 60 miles southeast of China Grove in Lincolnton, North Carolina — at the razor’s edge of Gaston County — stands another little white farmhouse. Jim and Mary McMahon live there. Jim, a Massachusetts native who — to the southern ear — still speaks with a heavy accent, says they couldn’t believe their luck when the house and its ten acres went on the market a few years back. After his retirement, Jim had planned to live with Mary on their son Eric’s 12 acres and to help him, his wife Jen, and their eight-year-old daughter with their sustainable farm.

Then a neighbor came to them with an offer. Would they be interested in the place next door? “Good people,” Jim says. “They gave us a good price, and we were like, ‘Okay, I guess we’ve got a farm now.’” With his newly planted fruit trees and his golden November fields full of goats and chickens and calves refusing to leave their mothers’ sides, “This is paradise,” Jim tells me. “And I want to maintain that paradise.”

In 2016, an Australian company called WCP Resources Limited launched a quiet campaign through its US subsidiary, Piedmont Lithium Inc., to acquire thousands of acres of residential, farm, and wild lands in Gaston County. Specifically within the Carolina Tin-Spodumene Belt, a 25-mile-long strip that runs from North to South Carolina and contains the country’s most substantial hard-rock deposit of lithium, an element that is widely used in batteries for electric vehicles.

Over the course of the next five years, Piedmont engaged its investors and global partners about plans to build one of the largest lithium mines in the United States. It gained a land position of more than 3,000 acres through what it called an “aggressive” strategy. It applied for and was awarded the Clean Water Act Section 404 Standard Individual Permit, the only federal permit required for the development of a lithium mine. It made a five-year, fixed-price deal with Tesla to supply the automaker with spodumene concentrate (SC6), the raw material for making batteries, from its North Carolina deposits, sending its stock prices soaring. And in late 2020, it announced plans to redomicile in the United States.

The timing was fortuitous. In an executive order issued during the first year of his presidency, Joe Biden pushed for electric vehicles, which currently rely on lithium-ion batteries, to account for half of all new auto sales in target year 2030. The Inflation Reduction Act, signed into law the following year, provides incentives for the domestic development of critical mineral supply chains and US free-trade partners, sets aside billions of dollars in funds for battery and battery-component manufacturing and recycling, and limits EV tax credits to vehicles containing batteries either partly made or recycled in the United States.

While these and other federal and state policies have favored the creation of a domestic lithium supply chain, and while market analysts, policy wonks, and many environmentalists have embraced it as a tool to address climate change, lithium mining comes with its own set of significant environmental costs.

Meanwhile, most of Gaston County remained in the dark about the details of the Piedmont project. It was all patchwork then, bits and pieces of information shared on back porches, in grocery store aisles, and over dinner with friends. Then Piedmont started showing up everywhere. They were involved. They were at baseball games, on hiking trails, at the local rodeo arena, and handing out candy in the Cherryville Christmas parade. Still, almost no one knew their plans.

Brian Harper, who lives and works on an idyllic 12-acre lot in Bessemer City, says he tried to get to the bottom of things in those early days. He says he called and asked one of Piedmont’s contractors — a guy who had been visiting his neighbors and doing his damnedest to buy their land — to come see him at his shop. Harper, who is in his fifties, runs an industrial-gear manufacturing business called Stine Gear and Machine Company out of a barn-red steel frame building at the edge of his property. He plans to pass the operation on to his daughter, just as his father passed it to him. “We stood on the shop floor,” Harper says, “and I listened to what he had to say and told him I wasn’t sure what they were doing would be a good fit for our community. He said, ‘Well, to be honest, it doesn’t really matter what you think. Right where I stand will be a 500-foot pit.” Harper says he made up his mind about the Piedmont project right then.

At the end of 2020, Piedmont had not yet submitted its state mining permit application to the North Carolina Mining Commission, despite having twice extended the target permitting timeline it had shared with investors. Nor had the company made any formal contact with the Gaston County Board of Commissioners about local zoning changes necessary for its project to proceed, though it had said in press materials that it “generally expected” the county to support its project for economic reasons.

By early 2021, members of the board had become impatient with Piedmont’s silence. Day after day, the calls came in, concerned citizens pleading for answers. How much land did Piedmont plan to buy? How long would they stick around? Where did they plan to dig and how deep? Would wells run dry? Would there be arsenic or other toxic chemicals or heavy metals in the drinking water? How much blasting would there be at the mine? Would it be dangerous to breathe the dust? What would happen to their children, their crops, their cows, their chickens? What would happen to the birds and deer that wandered across their land? What about the traffic, the noise? Would their homes be taken? What would happen to the lives their families had built out of the North Carolina soil for the last couple years, or decades, or centuries?

In emails released as part of a WCNC Charlotte Defenders investigation, board members fretted about the absence of information from Piedmont. “Why are we the last to know the plans of this organization?” asked commissioner Chad Brown. “We have yet to hear anything of substance, but everyone else has. I’ve been asked more from people for or against this site, but nothing from Piedmont. It’s hard to say or tell anyone other than no one has presented ANYTHING to us.”

That spring, Piedmont accepted an invitation to appear before the Board of Commissioners to finally outline its proposal. Board members said the company backed out days before the scheduled meeting. They weren’t ready to present in March, they later told commissioners. They didn’t know their plans. Shortly thereafter, the Wall Street Journal released an inside look at Piedmont’s efforts in North Carolina along with a multi-photo spread. “America’s Battery-Powered Car Hopes Ride on Lithium. One Producer Paves the Way,” the headline proclaimed.

“We’re going to build a really big business,” former investment banker and Piedmont CEO Keith Phillips told the Journal.

When Piedmont did finally come before the board in July of 2021, Phillips told the commissioners that Piedmont had done an “exceptional” job developing the project technically and building a global strategy. “We haven’t done as good a job — and I blame myself — with the community,” he said.

While Piedmont had failed to engage Gaston County residents, it had for years been building relationships with prospective customers, federal agencies, state mine regulators, local schools, and local nonprofit organizations. The project Piedmont was developing, Phillips went on to say, was considerable — four 500-foot pit mines and a lithium-hydroxide processing plant on a 1,548-acre integrated site in northwest Gaston County. It would require an $840 million capital investment. The commissioners were nonplussed.

“This is the biggest case in my 23 years of sitting here of putting the cart before the horse,” commissioner Tom Keigher told Phillips.

“It’s going to be much easier to get $840 million than it’s going to be to get community support,” said commissioner Tracy Philbeck, “especially if people feel that their concerns have not been taken legitimately.” Members of the board responded to Piedmont’s failures by refusing to consider zoning variances until after the company received its state mining permit.

Piedmont submitted its state mining application that same August. Since then, it’s been asked to submit more information three times: first in October of 2021, again in January of 2022, and once more in May of 2023. The company’s deadline to respond to the January of 2022 request was extended twice, while its most recent deadline has been extended through May of 2024.

The company has since amended its Tesla deal to supply the automaker with SC6 from its joint project in Québec at a floating price for a three-year term, with an option for renewal.

Open-pit mining is a rough business, and if the Piedmont project advances, there’s no doubt there will be scar tissue. Miners will dig a pit 500 feet deep, drill holes in the rock, pack those holes with dynamite, and blast. Large rocks will be crushed in the pit and sediment will travel via a covered, electric-powered conveyor out of the pit and over to the chemical-processing plant. Other valuable minerals will be sorted at a second on-site facility and sold, while excess rock will be used to progressively “reclaim” the pits. One of the pits will remain open and be allowed to fill with water. Piedmont will own and manage that pit in perpetuity. Remaining waste rock will go into a separate stories-high pile on the property.

Federal and state permitting requirements are designed to mitigate and monitor the environmental impacts of lithium mining, but permitting relies heavily on due diligence, self-monitoring and reporting, and forthrightness from the applicant during the application process and throughout the lifespan of the project.

For the many Gaston County residents who’ve expressed vehement opposition to the Piedmont project, the question of trust is a serious one. Again and again, the company has said it wants to be a good neighbor. But can Piedmont be taken at its word?

On a Tuesday in early December of last year, I called commissioner Chad Brown from the road. Brown now serves as chairman of the Board of Commissioners, and he has just announced his primary candidacy for North Carolina’s secretary of State. A former professional baseball player, he no longer has fans lining up in the bleachers for his autograph, but he has not lost his easy charm.

Brown is in his truck with his teenage son when we talk, and he puts me on hold when they pull into the driveway. “Hey… hey,” he says to his son, “don’t look at it, don’t even look at where it came from.” He is talking about a delivery that’s been left on the porch. “Sorry,” he says when he comes back to me, “Christmas presents.”

When I tell Brown that members of the board seem to be uniquely bonded to their electorate, he tells me he believes that’s a result of open and honest communication. “People here,” he says, “they generally care about what’s going on around them. There are thousands of years of history in this county, many generations that go way back. The people who live here, they don’t want to be uprooted.”

Brown is sensitive to his role in the ongoing Piedmont saga and says he has done his best to be equal-minded. “I’m all for growth in Gaston County, but I have to ask tough questions because that’s what the citizens want from us. And they deserve to get answers. If I get this wrong, I’ve done everyone wrong, including Piedmont Lithium,” he says. “Our job is to make sure that all the parts of Gaston County are thriving, not just some.”

I ask whether — in Brown’s opinion — Piedmont has done enough to earn back the community’s confidence in the two and a half years since it first outlined its plans. “No,” he says, “and I don’t mind telling you that.”

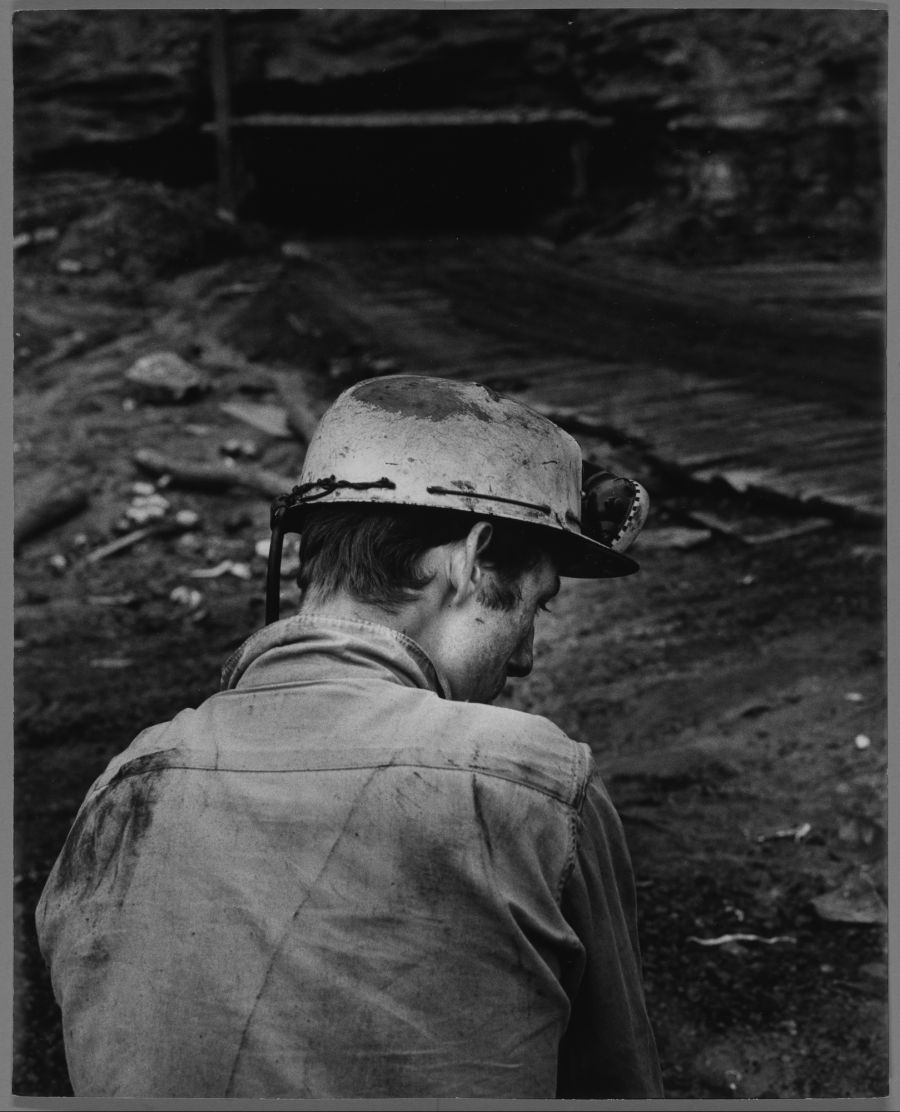

Though Piedmont has pointed to a legacy of lithium mining in Gaston County, local mines that supplied pharmaceutical companies and makers of nuclear bombs with lithium for about 30 years, beginning in the 1950s, are dwarfed by the Piedmont project.

These days, Gaston County is farm country. It has its conventional farms with their eternal rows of monocrop corn and soybeans, and it has its homesteads, too, like the ones Jim and Eric McMahon have started. If it is nothing else, it is a community that understands what it means to have your hands in the dirt, to be rooted and built up.

Warren Snowdon, who — with his wife — owns a certified tree farm on a couple hundred acres that edge up against the Piedmont property, says it's about connection. The names of the roads here are the names of the people who made this place what it is, the names of families who still live and thrive here. Now, they’re the names of his children. “There are four generations of farmers in this family,” he says. “That’s how deep this goes.”

When, in August of 2023, Piedmont came before the Board of Commissioners for a second time, it was asked whether it would agree to limit the scope of its project to the area it has defined in its mining-permit application. It was asked, that is, if it intended to absorb even more land into a footprint that is already measured in thousands of acres. Though company representatives suggested that Piedmont might be willing to define the boundaries of its activities in a Community Development Agreement, following the meeting, it released a printed Q&A that clarified its response. “We would not want to be limited to the current proposed mining permit boundary,” it said. “We have already defined lithium resources in other areas of the Carolina Tin-Spodumene Belt that we believe have tremendous value.”

I ask Jim and Eric if they believe the Piedmont project will continue to grow, and if it does, whether that will change the way people live here. “I don’t see how you could argue that it couldn’t change it,” Jim says. “One of the things about the culture here is… I just got 12 bales of hay from a guy in Lincolnton. What happens if they put him out of business? How do I feed my cows in the winter? It might be hard for some people to understand, but we do things for other people here.” This is how Jim understands neighborliness. “We barter,” he says. “Maybe I’ll give them meat, and they’ll give us fresh fruit. If we can’t do that anymore, it interrupts our whole way of life.”

We are standing outside a greenhouse Eric and his wife Jen put up and take down seasonally. Inside are winter greens and tomatoes and a banana tree Eric says “comes back every year.” Eric calls this his “redneck village,” and his hens, hidden behind the walls of their just-built coup, chime in cautiously. “It’s the ‘What if?’ question,” Eric says. “And they want to say, ‘Well, we’re gonna… we’ll be careful,’ or, ‘We’ll see what happens,’ but this is a huge company looking to make a lot of money. They want to come in here, strip mine the place, and leave. Will it create some jobs? Sure, for a few years. And then they’re gone. But are they going to invest in what we have here? No. They’re going to come, take what they can, and move on.”

Though Piedmont has not yet been able to provide any detailed information about how many parcels sit within its blast radius, it estimates that some 550 homes are within 1,500 feet of the boundaries of the project. In August, a representative from Piedmont partner Austin Powder Co. told commissioners and residents that although vibrations would be felt up to and perhaps beyond 3,000 feet away from the blast, compliance with federal regulations relating to blasts was certain to prevent any and all damage to homes. Further, Piedmont says, it will refrain from blasting on weekends and after dark.

Harper is uniquely positioned in all this. It’s not just his home he’s worried about, it’s his livelihood. Because of the nature of his business, he says, a business that relies on advanced manufacturing processes requiring accuracy to a tenth of a thousandth of an inch and taking as many as 15 hours to complete, his operation cannot tolerate any level of vibration.

Harper, who lives within eyesight of the entrance to the east pit, says he reached out to Piedmont early on about the possibility of relocating the business, something he says he has no desire to do. He estimated the cost of moving at $250,000. Then, he says, Piedmont went quiet. Though Piedmont declined to comment for this story, Phillips told the Huffington Post in 2022 that Harper’s claims were “completely inaccurate.”

“To be crystal clear,” Phillips said, “a man with a machine shop who needs a quarter-million dollars, do you think we’re going to let him stand in the way? If he needs a quarter-million dollars, we’ll find him a quarter-million dollars. That’s the world’s easiest answer. But we want to really understand it. We’re actually not convinced it’s true that anything we do will have any impact on what he’s doing.”

I ask Harper if he has seen Phillips’s response and how it makes him feel. He is mild, almost shy, when he answers. He says he feels like Phillips was brushing him off or suggesting that he was lying. “Lately,” he says, “I’ve spoken to their very nice PR lady. She has offered to get a blasting study done. Of course, I would prefer an independent study.”

There’s also the fact that lithium mining and processing is by its nature water-intensive. If the project moves forward, and the company excavates, its mines will flood with ground and stormwater that will be pumped out into sedimentation ponds for testing and some level of treatment. By the company’s estimates, it will pump out roughly one million gallons of groundwater during peak operations, daily.

In northwest Gaston County, where the water table is uniquely close to the surface of the Earth and where most residents rely on wells for home and agricultural use, there are legitimate concerns about wells drying up.

Piedmont, meanwhile, has been reliably tone-deaf. “The promise and purpose of electric vehicles,” a Piedmont spokesperson wrote in a 2022 op-ed printed in the Gaston Gazette, “is to help us reclaim our planet, including our water supply… Electrification of our infrastructure will be one of the major ways we protect and preserve this precious resource."

Early on, Piedmont suggested that only a small number of wells, if any, would be affected by its activities. Since then, it has been unable to provide any meaningful estimates as to how many households and farms might be at risk of losing their water security. If a well does run dry, Piedmont says, the company will respond on a case-by-case basis. In the short term, it will provide a household with bottled water for up to 45 days or may supply a tanker, depending on the existing well’s use and flow rate. If the wells remain dry, the company will connect households to a municipal water service, if practical, or otherwise dig a deeper well. If it can’t restore access to water by digging a deeper well, Piedmont has said in state filings, it may either continue to try to extend municipal service or engage in “good faith” negotiations with the owner to purchase the property.

Gaston County residents are equally concerned that naturally occurring arsenic, abundant in the area, or other harmful chemicals will be released into their water during the mining process. I ask Eric if he’s worried. “Of course I’m worried,” he says. “If my well gets poisoned, I can’t do anything to fix that. There is no Band-Aid. The Band-Aid is ‘find other water.’”

Eric says he and his wife did have a conversation about whether they should relocate. “We don’t want to do that,” he says, “and we’re not going to do that at this point, but of course we had to have that conversation.”

The future Eric sees for this place is a better life for his family. “You know,” he says, “you worry about the world, you worry about things, and even if things go well, you want to provide a better life for your kids. For us, we want to know what’s in our food, and now we do, because we grew those vegetables, we raised those animals.”

I ask Harper whether he thinks Piedmont has lived up to its promise to be a good neighbor, and he says it depends on your perspective. “Where are you bringing your perspective from?” he asks. “Do you have a country-living perspective? Because out here, a good neighbor calls to check on your mom because they already know your mom has been sick. Does that happen in a big city? It’s a different school of thought. They could be what they call a good neighbor somewhere else, but not here.”

Chad Brown says scripture has a lot to say about what it means to be a good neighbor. “The Lord talks about treating our neighbors as we do ourselves. And when I think about how I want to treat my neighbors, I want to invest in their land, their homes, their children. And I don’t care if I get anything back,” he says. “I’m worried we’re losing sight of that foundation — that compassion you have in your heart.”

At the little white farmhouse my grandfather grew up in, I walk the roads. Juanita and Miss Jolly are no longer there, but there are new neighbors now and new friends to be made. My neighbor lets me pet his pregnant horse’s belly. I teach my neighbor’s kids about prickly pear and shelf mushrooms. My neighbor tells me about his time in Vietnam, and I give him the hat off my head. I am still living in my grandfather’s American dream. But who knows for how long?