Swifties

Pop Princess Takes Seattle

70,000 females fill football stadium at $1500 and up per ticket as glittery-eyed psychotics roam the streets

Will deliverance arise from the outstretched hand of Taylor Swift?

Picking glitter off the carpet of the Ace Hotel in Seattle in the dog days of August is the reward I get for leaving home and venturing into the great beyond. Every year, at around this time, I descend from my farmstead in order to report on what remains of the America I once loved, and still have strong feelings for, despite the bitter taste of ashes in my mouth. “They’re Taylor Swift fans,” the woman cleaning the floor beside me helpfully explains. “They’re very nice, but they leave glitter everywhere.”

Taylor Swift seems like the least of Seattle’s problems, though. It’s not that city people are rude by nature, as I explained recently to one of my neighbors. It’s that the math is different, when basic social interactions like stopping to say “hello” or give directions might bring you face-to-face with a being whose psychotic pain-ridden inner landscape hopefully does not resemble anything that is familiar to you. The chance for effective communication under such circumstances generally being nil, the healthiest choice is to skip the pleasantries and keep on moving. Which is more or less why I moved.

Seattle is welcoming Taylor Swift, America’s reigning pop princess, on the last leg of her Eras tour, which is clearly the music event of the summer, with tickets selling for $1,500 and up, a price that made my non-attendance pretty much a no-brainer, until a music-lover friend, proclaiming himself to be tired of my prejudice against his teeny-bopper idol, offered me a ticket. I accepted his offer immediately, on the premise it was a tease. When the ticket arrived in the mail, I had little choice but to cover my bed by booking a flight here.

A few blocks from the Ace is a spot that specializes in Thai street noodles, which is a dish that I love but which is seldom available on my mountaintop. I sit down outside, and within five minutes a member of one of the street armies of the walking wounded, those that occupy the downtown areas of major American cities, strolls over and starts harassing the couple sitting three tables down from me. Or maybe crazy person isn’t the right term. He is in his early forties, well-muscled, and possesses an acute sense of just how far out he can act.

“I’m trying to go up in there,” he explains, making lewd gestures with his hips towards the expressionless Thai waitress indoors. “Like, I want to fuck her, get up inside her pussy.”

The dining couple pretend to be unbothered, having perfected the distinctive, glassy-eyed stare with which American urban-dwellers have learned to greet the more unpleasant aspects of their daily reality. I’m not here, the stare proclaims. You’re not here. I’m not with her. He’s not with me. I’m not human. You’re not human. You could cut off my head, or grow three heads out of your neck in place of your one head, here in front of the $8.50 cupcake store. I would still notice nothing.

It’s cowardice, of course. But I hardly blame them. What bothers me is that it’s also something worse, namely the pro-active severing of human bonds and shutting down of accompanying human perceptions which urban-dwellers, and many of the rest of us, have now learned to do by rote — like subjects of some 1960s lab experiment in which college students were made to play prison guards and give each other electric shocks. Maybe by fast-forwarding through the unpleasant parts, we might arrive together in an abstract, connectionless space in which no one has any responsibilities to anyone, and then the monster in front of me will disappear or wander off elsewhere for prey, or to find drugs.

When the blank stare fails to produce its desired effect, the crazy person takes his act a step further, leaning in a full foot and a half into the couple’s personal space. “I’m going to sit here, and I’m going to watch you chew,” he explains. With the male of the couple showing no apparent inclination to enter street-fight mode, and his date still sitting motionless in her chair, the homeless man becomes chatty, and explains further, drawing on what appears to be a wealth of experience with Seattle law enforcement.

While the Seattle police department, like the New York police department of my 1970s childhood in Brooklyn, still exists, it has adopted its own departmental version of the blank stare, after being publicly neutered by the city’s last Mayor, Jenny Durkin. A former Federal prosecutor who imagined the name “Jenny” made her seem friendly to young people and immigrants, and who tied her “legacy” to building a new generation of climate-friendly sports stadiums to gratify the passions of her wealthy backers who saw their future in aligning themselves with the corporate liberal state, Durkin’s downfall was caused by a fatal lack of IQ points. This failing, which was both political and personal, became apparent when she encouraged the city’s standing army of protesters, outraged by a host of social ills including the possible re-election of Donald Trump, climate change, and the police killing of an African American drug addict named George Floyd in Minneapolis, and bored shitless by COVID lockdowns, to establish an “autonomous zone” called the CHAZ in the city’s Capitol Hill neighborhood. While every American city in 2020 had a standing army of protesters who were angry about George Floyd, and climate change, and eager to battle the police, the politicians who egged them on understood the purpose of these manifestations, which was not to actually destroy their own cities or turn downtowns into open-air smoking and shooting galleries, but to make use of their pent-up lock-down energies to put on a show that would frighten the normies out of re-electing Trump.

What Durkin, like the people in charge of San Francisco and Portland, didn’t get was the point of the show, which was to put a Democrat in the White House. Instead, she took it seriously, and became a kind of ditzy official cheerleader for the CHAZ, proclaiming that it to be an adventure in the carnivalesque spirit of 1960s street theater. As the CHAZ became a lawless, violent freakshow, Durkin forced the city’s female African American police commissioner to step down, thereby alienating the city’s police officers, business owners, and ordinary citizens who didn’t wish to be physically assaulted.

Memorialized as the martyred victim of surly right-wingers, Durkin was in fact an example of a new breed of Democratic Party politician whose desire to engage in pre-approved social signaling within the country’s elite managerial class outweighed any sense of obligation to the welfare of her constituents or basic common sense. Driven from office by Seattle voters, Durkin can still no doubt count on a lifetime of national-level corporate and political appointments for having upheld the party line. The landscape of shattered social trust that she left behind is incarnated in people like the psychotic, who is busy educating the couple next to me about how Seattle works now.

“You can call the cops,” he continues. “They’re just going to laugh at you. I’m standing here doing nothing. I’m just standing here and looking at you, which is perfectly legal. So they’ll laugh, because they know they can’t do anything. It’s a public sidewalk. In fact, they’ll blame you, for making them feel bad about the fact that they can’t do anything to me.”

Crazy? Maybe. But if I’m the judge, then it is my opinion that the wandering psychotic knows exactly what he’s doing. Another uncomfortable minute passes before a short but well-built Thai man arrives with a large Rottweiler on a chain, and nods to the waitress indoors.

“It’s time for you to go,” he tells the man on the sidewalk who is now eye-fucking his dog. “If you don’t leave now, I will go inside and get my bat.” After a swift exchange of epithets, comprehension dawns, and the psychotic walks away, grinning. “I’ll be back tomorrow,” he promises. “This ain’t over.”

I think back to my Uber driver from the airport, an exceptionally polite older man from East Africa.

“Have you heard of Kenya?” he asked me. “Sure,” I answered. A lot of Kenyans have settled in Seattle because there is work here, he told me. He hadn’t seen his family in 19 years.

When I asked him if the separation is painful, he nodded yes. It’s the American sickness, he explains. “Dividing people from their families. Destroying families,” he continued. “Leaving people with no connections, alone.”

I suggested that perhaps disintegrating the social bonds that keep families and communities together is just the darker side of America’s freedoms, which include the right to become whatever you dream up tomorrow. “It’s not freedom,” he answered bitterly. Then he tapped the side of his head. “It’s how you destroy people from the inside,” he explained. “It’s how you turn people into animals.”

At the corner, a country club-looking family of five disembarks from a blue Tesla Uber ready for their big adventure downtown to see the Taylor Swift concert. The mother, who is a nice-looking woman in her forties, and her daughter, who is in her mid-teens, wear matching white glittery dresses. The middle daughter, in her early twenties, wears black, with a row of maybe a dozen friendship bracelets on her right arm.

It makes sense that Taylor Swift compels their allegiance, being the closest thing that America has these days to a national hero who connects the country, the country club set included, to its foundational mythos. F. Scott Fitzgerald would have loved Taylor Swift. A little bit cracked, a little bit reckless, bound for disappointment, but protected by invisible cushions of race and class, she is everything that the country club set fears and admires, her tragedy being at once fore-ordained, and at the same affirming the existing order. She is Zelda, Daisy Buchanan, Sara Murphy, and all the girls in F. Scott’s stories about winter-time in St. Paul, Minnesota rolled up into one. If “Cruel Summer,” Swift’s radio anthem of the moment, isn’t exactly Cole Porter, it’s easy to imagine F. Scott sharing the tune with his daughter, Scottie.

The economics of tonight’s Taylor Swift concert are the flip side of the social reality of places like Seattle. Assuming that the family got a good deal on tickets, at maybe $1,500 a pop, tonight’s night out downtown still amounts to the down payment on a new Toyota, or a Tesla. I join them in the mile-long walk to Lumen Stadium, which sounds like a gag from Severance, the dystopian Apple TV show in which workers volunteer for surgically-induced dissociation between their work selves and the people they are at home. Maybe the stadium is an ad for the show.

And yet, even here, there is no denying the sweetness of rock and roll music in the summertime, whether you choose to tune in to a concert, tour, show, or festival, or simply to the radio in your car. Every summer I pledge my allegiance again — not to America, which is a place that still exists vividly in my mind, but which I am finding depressingly difficult to locate according to familiar space-time coordinates, but to those old hormonal chords.

So far this summer, my best summer concert experience was the Pixies, a band I saw for the first time outside Boston when I was 18, and which I saw again this summer while standing in the rain with my daughter at a local brewery an hour’s drive from my mountain home. The Pixies are older and a bit mellower now, but otherwise exactly as I remembered them. Joey Santiago, the Pixies guitarist, is a Puerto Rican surf-rock punk who shreds against the grain in a lyrical way that calls down the angels. Who could imagine the weird, distinctive angles that made Joey Santiago dance with angels, aside from Joey? The bassist, Kim Deal, who once dated a music writer colleague of mine, now resembles a more gently aging Patti Smith crossed with MTV’s Daria. Her own band, the Breeders, which she founded with her sister Kelly, a nurse in Ohio, is also on tour this summer. Charles Thompson, the Pixies’ lyricist/lead singer, is fat and bald, but still radiates his uniquely scary aesthetic energy, which marries a kind of Shakespearian nursery rhyme approach to songwriting with dashes of Johnny Cash’s “Man in Black” and home-made santeria rituals in a kind of avant-garde Black Mass. My daughter loved it. I am hoping the memory will enter her bones and sustain her sense of the possibilities of American song. Which is why I am happy to stand in the rain, or to occupy the cheap seats of a local football stadium with the bass kicking off the concrete facing of the third tier. If they’re playing, I’m paying, until my maple syrup money runs out.

And even if nothing can truly compare to the Wings Over America tour, or the first Led Zeppelin tour, or the Stones’ Some Girls tour, or the first David Bowie solo American tour, or Foghat, those were truly only rumors, filtered through the conversation of the older kids’ hallway and playground, though what we saw in the coked-up 80s wasn’t bad, either — the Grateful Dead, Bob Dylan, Tom Petty, Neil Young. I recall the ferocity with which the Shea Stadium crowd booed The Clash for playing an hour of punk-inflected reggae for a crowd that had come to see and hear The Who. The louder they booed, the louder The Clash played. The lesson stuck: You are free to boo, and I am free to play louder. It was the spirit of punk rock, which was not all that distinguishable from the spirit of America back then.

The Pacific Northwest, the region Taylor Swift and I are both visiting tonight, has its own claim on the American spirit, being a home of the weird, individual genius that refuses to be colonized by the prefab tribal narratives of which today’s Americans seek to order our shared reality. Jimi Hendrix, the greatest genius of American music of the past half-century, was born in Seattle; he joined the US Army, became a paratrooper, then went to New York and became a hippie. Go figure that. Kurt Cobain, who defined the 90s American sound with his Beatles-esque misery, grew up with his bandmate and protector Krist Novoselic in Aberdeen, a decaying logging town near Olympia, which was home to Sub Pop — the label that invented grunge — and Kill Rock Stars, which presented the even more gorgeous and miserable songs of Cobain’s true heir, Elliott Smith. The Ventures, the pioneering surf rock band, were from Tacoma, Seattle’s dark twin and America’s serial killer capital. None of these geniuses nor the music they made were products of settled forms or trends, nor can they be easily modeled by AI.

American art has never been about conforming to anyone’s politics or restricting expression; it’s about speaking the truth of our unique encounters with the mega-wattage of weirdness that America puts out, which is in turn the product of the tension created by the opposing forces and influences that shape us both as individuals and as a nation. “I know a wind in purpose strong,” Herman Melville wrote in “The Clash of Contradictions,” a poem which doubles as a crash course in the aesthetics of the American voice, “it spins against the way it drives.” Tell Melville that Moby-Dick is a book “about whales” and should be studied only by cetology experts, or Ralph Ellison that his work must be understood through the lens of “the African American experience” as certified by tenured ideologues, and they would likely punch you in the nose — and, in the good old days, at least, be applauded for it.

Taylor Swift is a pop star. Neither a brilliant singer nor a gifted dancer, she is a writer of memorable lines and couplets that seemingly emerge from a stream-of-consciousness story-telling voice whose seeming artlessness is a calculated effect of her songwriting craft. Her persona is a disenchanted version of the girl next door, who is overly labile, loses control of her emotions, gets dumped, and then pours out her simmering anger and hurt to her diary, and to her millions of fans, for whom she serves as a kind of substitute for family. Her awareness of her own failings is the whetstone upon which she sharpens her daggers, which she thrusts into the eyes of those who have injured or betrayed her, a list which apparently includes every man she’s ever dated. Her own family is an upscale affair, consisting of her young brother Austin; her mother Andrea, a former marketing manager at an advertising agency; and father Scott, a stockbroker-turned-vice-president for Merrill Lynch, who manages his daughter’s money.

Awaiting her arrival, the inside of Lumen Stadium is an explosion of cut-off jeans shorts over fishnets, prom dresses, glitter tops, shimmery metallic leggings, single eyes outlined in glitter hearts, glittery tiaras, henna tattoos, rainbow glitter tops, glittery cowboy hats, and more glitter. It’s like Planet of the Apes for Women Wearing Glitter. There are moms and daughters, big sisters, BFFs, besties taking selfies on the steps, in preparation for the big event, which is Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour — not the “Eros” Tour, as I heard a late-night Seattle DJ say on the radio. The Eros Tour is very 1990s. Perhaps half the women here are seriously overweight, which is more or less the same ratio I’d expect to find among the men at a football game, except the men would be dressed like slobs. The spectators here look dressed for a summer prom, proving once again that the audience for female finery is other females. Maybe one out of every ten spectators is a man — dads, boyfriends, and gay couples. Relations between the sexes are cordial.

Opening Act #1: Gracie Abrams, is the daughter of pop auteur JJ Abrams, whose own career might serve as a kind of Rosetta Stone for understanding how Hollywood stopped making movies and television shows that anyone in America willingly chooses to watch for anything other than pure repetitive narcosis. After establishing his serious movie director credentials with Regarding Henry, the unbearably narcissistic and manipulative Harrison Ford vehicle with a mirthless script by Mike Nichols which will surely live on as the low-light of the career of the fantastically talented director of The Graduate, Abrams rocketed to pop culture stardom with the hit TV show Lost, which became the gold standard for successful commercial entertainment in the first decade of the 2000s. Abrams’ success with Lost gained him the necessary cred to direct the two worst 3rd generation Star Wars sequels, which he turned into boring two hours-plus long fantasy cosplay ads for the progressive wing of the Democratic Party. Now in his fifties, Abrams looks like a central casting amalgam of a CNN talking head and an attendee at the annual conference of media and technology moguls at Sun Valley.

What’s most objectionable about the through-line of Abrams’ career, and the careers of his generation of directors, show runners, and executives, isn’t some big screen parody of progressive politics, though, or even transparent opportunism. It’s the absence of laughs. Laughter is a danger to the corporate monopoly pipelines and content-aggregation businesses. It could make someone mad and ruin your brand. Worse, it might suggest that your vision of reality is not exclusive, and perhaps not conducive to the greater good. Which is why the first thing people with totalitarian ambitions do with their power, like monopolizing the entertainment business as an adjunct to the creation of privately-owned information pipelines, is to eliminate laughter. Jokes have a tendency to expose and thereby undermine arrangements in which people aggregate enormous amounts of power to themselves at the expense of everyone else. Which is why today’s Hollywood prefers nepotism to laughs.

Gracie Abrams, daughter of JJ Abrams, is a polished nepo baby who plays the role of Taylor Swift’s younger confidant who is hoping someday for her own shot at stardom by promoting her closeness to the Queen Bee. “A couple of weeks ago, Taylor blew my mind by inviting me to sing my song with her,” Abrams confides. She’s at the stage of her artistic development where her songs sound like polished versions of other people’s songs. Her selling point is her relatability, which has doubtlessly been helped along, like her music, by growing up in the Abrams household, and with an added dose of the best production and coaching that her father’s money and connections can buy.

What bothers me about the nepotism part of the Gracie Abrams storyline isn’t that the singer is undeserving of stardom. Nor its violation of the ideals of meritocracy, which the country’s leading institutions delight in finding new pretexts to violate, by way of displaying their loyalty to the ruling elites. Passing on skills, values, and human connections to one’s children is, or should be, a normal part of how families function. It is why families exist in the first place. What bothers me is that, under cover of notions like “fairness,” nepotism, like families, has become a luxury that only rich and powerful people can afford, like what JJ Abrams can provide for his daughter, leaving the rest of us out in the cold.

What money can’t buy, even with the advent of AI-powered songwriting tools, is something to say. In the absence of which, watching Gracie Abrams sing in front of 70,000 people in Seattle feels a little bit like watching Saddam Hussein’s daughter entertain a soccer stadium full of people in Baghdad.

“Thank you so much, Seattle. I love you so much forever,” Gracie Abrams emotes, adding, “have the greatest night, I mean senior summer. Or whatever.”

Or whatever.

Haim, unlike Gracie Abrams, can rock. They know all the moves. They make cock rock fun for girls, while showing that being a woman with an ass and boobs can be fun, too. But because they lack any outsize musical talent, at stadium level their charm wears off by their third song. To put it in cruder terms, watching the Haim girl crunch basslines is like watching a straight girl with a strap-on pretending to be lez, and maybe getting into it enough to impress both the girl she’s fucking and her boyfriend, who is also maybe a little weirded out. Because, in the end, cock rock is all about — well, you get the point. AC/DC would blow these fine sisters off the stage in 10 seconds flat, as would Megan Thee Stallion. On a narrative level, which is where Haim has mostly chosen to situate itself, I would argue that the 1990s Starbucks coffeehouse sensation Jewel is heavier than all three Haim sisters put together, simply by virtue of being from Alaska.

“Seattle! How we doing?!” Haim Sister #2, the serious-looking blonde one, calls out. “I’ve got murder on my mind!” It’s the lead-in to a video they did with Taylor, a version of Knives Out! where everyone apparently had fun dressing up.

“I’m gonna be hungover

I’m gonna be hungover

I’m gonna drink a bunch of different drinks

And I’m gonna be hungover”

The Haim sisters are fine young women, especially the two younger sisters, who rock a more robust, physically-and-mentally healthy Sarah Silverman-type vibe. What they lack is the comedienne’s awareness of her own brokenness, which was the source of her charisma and wicked sense of humor. Sarah Silverman knew that the world can be a mean, cruel place. Where young American men are generally forced to internalize that lesson in unpleasant ways before they hit puberty, young women are programmatically encouraged by schools, older women, and every form of entertainment on the planet to believe they can have it all. To believe otherwise is to let down the side, which consists of all other women on the planet.

The result being, at least here in America, the near-certainty that they will fail to achieve even basic levels of happiness, an outcome which could have been easily foretold by taking a good look at their own mothers, American women over 40 being the most uniquely miserable group of women on earth, having been hopelessly fucked over by the incommensurate demands of marriage, family life, and jobs that can never provide enough income to both support a family and pay for childcare. Above all, they are crushed by having to do it alone, in the context of a socio-economic machine that is programmed to crush families as part of the larger program of social atomization being exploited by America’s newly-minted Gilded Age oligarchy. The role of fathers in this scheme, if they are lucky, is to helplessly indulge their daughters without being able to protect them, to watch their daughters stride into the bright lights of adulthood and shine there for a minute or two, as healthy 22 or 26 year olds, accumulating degrees and boyfriends or girlfriends and career points, before falling off the ladder and hopefully realizing that they are the victims of a scam.

“The first person we actually showed it to was Taylor,” Haim Sister #2 is saying. “She said this song was her favorite. It’s called ‘Dazzle Me.’” In the background, smoke machines are emitting very low amounts of smoke. Like the effects, the song fails to dazzle. It’s fine, like Haim, which in Hebrew means “life.” Take away the “I,” and you get “Ham,” which would have been a funny name for a band consisting of three Jewish sisters.

Haim’s set is followed by a behind-the scenes look at the making of a Taylor Swift music video. In the video of the video, the singer is wearing a giant N95 mask over her pointy features to advertise her vigilance against COVID. No one else on set is wearing one, and she discards the mask for the filming of the video.

Swift’s decision to advertise her allegiance to the COVID party on the big screen presumably has little to do with politics, though. It’s a nod to insurance premiums, which in the case of the Eras Tour must be stratospherically high. There’s also the fact that in the absence of the bad old patriarchy to protect them, unmarried women under 35 have become brides of the state, dependent on administrative bureaucrats and courts for everything from birth control pills and abortion, to guarantees of equal access to sports and education, to protection against words and ideas they don’t like, to predatory men. Unsurprisingly, they define themselves as some flavor of left-wing, liberal, or progressive by a ratio of 70-30, while every other American demographic, as defined by age and gender, colors themselves in some shade of red. When these women get married, they redefine themselves as wives and mothers — to be replaced by the next cohort of unmarried female voters under 35, who vote blue.

No one is here to check political boxes, though. They are here to celebrate their togetherness beneath the banner of the Queen Bee. Despite the fact that it is 8:17 pm, the continuous high-pitched, high-decibel cheering has failed so far to bring the singer onstage. A giant clock with roman numerals appears on the big screen, counting down the seconds to her arrival. With only 2 minutes and 23 seconds to go, I am feeling mentally exhausted, in a way that reminds me of my first day in a foreign country. I should note here that I have married two women, and am the father of a daughter, and that outside of circumstances involving the plausible threat of physical violence I overwhelmingly prefer the company of women to the company of men. My wife is an especially brilliant and capable woman, and if I was forced to live even one week in her shoes I’d become acutely homicidal. Still, a large crowd of women in a football stadium is another matter entirely. I have no idea how to predict their behavior.

What comes next is no surprise to the cheering crowd, only to me, as the plaintive, defiant strains of Leslie Gore’s doo-wop anthem “You Don’t Own Me” ring out over the stadium.

“Don’t tell me what to do

And don’t tell me what to say.”

An anthem of female independence, which depends on the existence of a patriarchy of overbearing men to protest against, it’s the perfect introduction to the vibe of Taylor Swift’s own music, which is indelibly of this moment, in its semi-wistful, and more than mildly schizophrenic hearkening back to relationships in which women are the weaker sex, under male control, and at the same time the stronger sex, asserting their independence by kicking men to the curb — the result of this dichotomy being the toxic combination of craziness and loneliness that defines modern American femininity, and by extension large portions of the rest of American life. It is the mark of Swift’s unique genius as a songwriter and popular icon that unlike, say, Madonna, she never gilds the lily. Instead, she embraces the contradictions of her desires and turns them into hits.

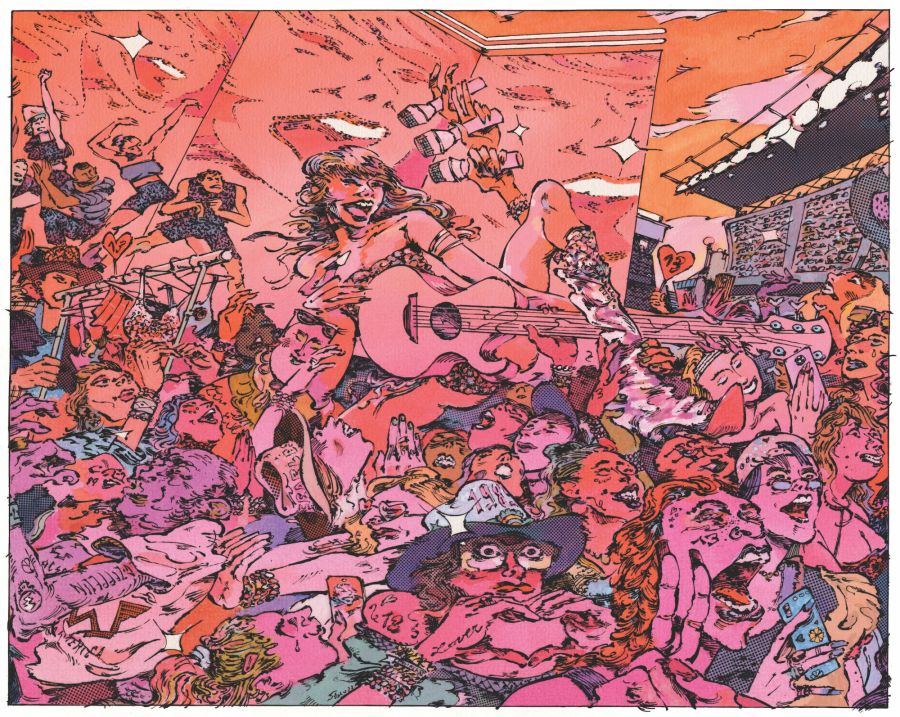

As we reach the minute mark, the crowd is approaching peak frenzy, counting down the seconds to Taylor’s arrival. As the clock hits the 10 second mark, the cheers and shrieks merge together in a single, paralyzing sound which suggests a rocket engine fueled by the high-pitched girl sound whose ability to stop everyone within a hundred-yard radius is vouchsafed to every human female by the age of three. A scantily-dressed Swift arises from beneath the stage atop a pop-up box, and instantly commands the entire stadium with “Cruel Summer,” a haute suburban version of a Fitzgerald Lost Generation novel with six stanzas and a chorus.

“It's cool, that's what I tell 'em

No rules in breakable heaven

But ooh, whoa oh

It's a cruel summer

With you

Hang your head low

In the glow of the vending machine

I'm not dying

You say that we'll just screw it up in these trying times

We're not trying.”

You go, Daisy! Part Khaleesi warrior goddess, part stripper, part show pony, part Dallas Cowboys cheerleader, part sorority sister, part Country Western singer, part Daisy Buchanan, part woman scorned, and part broken toy, her presence is effortlessly authoritative. The only parallels I can think of watching her are David Bowie and Michael Jackson, both of whom were also world-class dancers. Taylor Swift just stands there, commanding the stage, and the entire stadium, all by herself, with no band, and no backing tracks, or giant animal puppets, or fireworks; through the power of her persona, one she has assembled with her own magpie creativity, she’s taking colorful bits of string from the nests of her producers and songwriting partners and fusing them together in a way that is always uniquely her own. The key to her on-stage magic is her 360-degree awareness of her power over her audience, which in turn comes from an authentic sense of connection that Swift will work her heart out all night to maintain and strengthen.

“Let me try something,” Swift says. Demonstrating her connection to her audience, she points to one side of the stadium and the decibels rise to ear-shattering levels. Then she points to the other side, with similarly satisfying results.

“You just made me feel really, really powerful, Seattle,” she says. “You’re making me feel like I’m the first artist to ever play in this stadium two nights in a row.”

She follows this display of power with a Madonna-like dance number which is more or less a pro-forma display of girl power.

“I’m so sick of running as fast as I can

If I was a man

I’d be the man.”

The high-wattage clarity with which Swift smiles and waves from the Jumbotron while delivering her girl and woman power invocations creates an experience that is notably more intimate than the stadium concerts of my youth, when our heroes appeared from a distance as scurrying, feverish dots. It also lends itself to consideration of the singer’s distinctive physiognomy. Swift is not conventionally pretty. For one thing, her features are too sharp, especially her nose and chin. Her eyes are uneven, and a bit slanted. Taken together, the cast of her features and the flush of her skin projects a sense of physical discomfort, as if she is bothered by a rash. The result is a kind of moody discontent which can appear at any moment, obscuring the radiant sun of her pop star personality. As a songwriter she understands this effect fully, placing it in tension with her upbeat pop melodies and dance beats to form her persona.

Swift is not a dancer, either. On stage, she prefers striking poses and remaining immobile for long moments in the middle of routines, like an upscale mall rat version of the Statue of Liberty. Her dancing draws attention to her hips, which are not particularly fluid, and her boobs, which are normal-sized but unlikely to launch ships. At the same time, she never misses a mark; she works hard at every aspect of her craft. She is a perfectionist, who is highly aware of her own flaws, and has integrated them into her act, which is the right creative move. It’s also a pretty good working definition of mental health.

Swift’s genius as a songwriter comes from her rootedness in the themes and rhythms of country and western music, which is the genre in which she began, and which she has seamlessly adapted to pop. The marriage of these two forms allows Swift to channel the stresses and resentments of a generation of women who are hopelessly torn between the demands of the workplace and ingrained ideas of romance and femininity, and above all by the knowledge that the scripts don’t match, and never will match. No wonder American women, the single ones especially, all seem a bit crazy, and more than a little bit angry. Swift’s job in the culture is to take the toxic life-trap these women feel caught in and reflect it back to her audience, while singing and dancing in glittery costumes. Her songs mirror the brutal inner monologues of a generation of caged female animals who grew up with the language of girl power and are now unwilling to either fully endorse their condition or abandon the possibilities of romance. Around me, I can see close to a hundred women wearing t-shirts and sweatshirts and other forms of merch emblazoned with the legend “You Need To Calm Down,” the title of Swift’s hit song from her 2019 album Lover.

“We see you over there on the internet

Comparing all the girls who are killing it

But we figured you out

We all know now, we all got crowns

You need to calm down.”

What follows is a love bath in which Swift plays the bridesmaid to her audience, who, like her, are all Queens for a Night. “What an absolute thrill and a delight it is to sing these words to you,” the singer coos. “How on earth are you out here going this hard on a Sunday night? I need to know the exact components of this crowd,” she says, all bright-eyed and interested, like a girl on her first date with Mr. or Ms. Wonderful. “Is there anyone who went to a considerable effort to be here? Is there anyone here who put a lot of effort into what you are going to wear?”

The crowd raises its decibel level even higher. It’s a very feminine exchange of energy: Give a compliment and get a compliment. Swift is pleased. “This is a crowd that is just as loud as you are cute,” she proclaims. Continuing to model good manners for her audience, the Queen Bee includes her supporting act. “Will you make the most amount of noise possible for Haim?” The crowd is happy to oblige. Everyone is included in the circle.

Having dispensed with the opening emotional transactions, the evening will progress album by album through the story-line of Taylor Swift’s life and career, replete with costume changes, and an unending string of romantic disappointments, as memorialized in her dozens of hits. Swift has a charming way of presenting her life as a movie while at the same time fully inhabiting the characters in her songs. She’s a better actress than Madonna, in part because her persona rests on her relatability rather than being Superwoman. “I’ll be your host this evening,” she says with a ghost of a giggle. “My name is Taylor.” It’s like a cabaret act blown up to stadium size, held together by her easy intimacy with an audience of 70,000 people — which is a talent so unique that it’s hard to think of another performer, male or female, who could pull it off.

“All the king’s horses and all the king’s men

Couldn’t put me back together again.”

Alone onstage, she holds the attention of the stadium in a way no man could because, as a woman being looked at by tens of thousands of people, she symbolizes something more than pure ego. Being a woman implies the creation of life as well as its negation, so she symbolizes that, too. But no matter how famous she is, Taylor Swift suffers. Everyone in the stadium knows about her failed relationships and her break-ups. And unlike the previous generation of girl power avatars like Madonna, Swift doesn’t publicly masturbate with pink dildoes. In her life, as in her art, she seems entirely, though often unhappily, related to men. Which means that even as she projects herself outwards, in search of gratification from her audience, her audience trusts her to look inward, and to share their sorrows.

Swift’s persona is convincing because she suffers. She suffers because she wants too much, often from men whose inadequacies force her to settle for less, or much less, until she explodes, and leaves them long drunken answering machine messages, or stalks them at bars, or becomes obsessed with their new girlfriends, or takes her keys to the finish on their cars, or makes them the villains of her songs. It’s the suffering that makes her crazy. In other words, she’s pure Nashville. What’s most compelling about her stage show are the long stretches of time where Swift is onstage alone, whether sitting at a piano or playing an acoustic guitar, like a bright-faced newcomer at the Grand Ole Opry, where she started her career, when she was barely a teenager.

“Alright Seattle, are you ready to go back to high school with me?” Swift says invitingly, before launching into her early hit “You Belong With Me,” in which she casts herself as the girl next door in competition for the affections of a boy who hardly notices her:

“She wears short skirts

I wear T-shirts

She's cheer Captain, and I'm on the bleachers

Dreaming about the day when you wake up and find

That what you're looking for has been here the whole time.”

The real Taylor Swift dated a Kennedy, of course — but only for a few months. True to her personal brand, she then managed to screw up the nascent relationship with a series of borderline-scary faux pas, like buying a house near the family compound in Hyannisport, crashing a family wedding, and convincing the scion’s otherwise-highly-tolerant father that she was quite possibly more interested in the family name than she was in his son. So much for marrying in to American royalty. No matter how famous she gets, Taylor Swift will still be pressing her face up against the glass, and pouring belated regrets into her songs.

“You belong with meeeeeeee!” she proclaims, and the audience happily sings along, united in a feeling that every woman in the crowd can recognize.

Swift is America’s Female Id, injecting the feminine emotional range and insight of country music and injecting it into pop without compromising the virtues of either. But in order to play her chosen role, she is also forced to put huge amounts of energy into negating the idea of her privilege, which is a tax that is now being levied on artists by people who themselves tend to have little talent in the arts, but are backed by very large accumulations of political and financial power — and who control the corporate pipelines and sponsorships that allow artists to be heard. Swift evades the cultural strong-arm though a counter-aesthetic structured by the Nashville bones of her songwriting, allowing her to situate the ideas of being lonely and crazy within ideas of womanhood that are normative, and even retro. By embracing Nashville, she rejects the dominant elite aesthetics of defilement, which suppose an “us,” the defilers, and a “them,” consisting of those whose holy places must be destroyed. Swift’s music is the opposite of that.

“I think you did it / But I just can’t prove it,” she sings, flipping the script. Yes, I’m crazy — because you made me crazy. Haim returns to the stage and rocks out in witch costumes, adding an appealing rock and roll crunch to Swift’s normal diet of pop hooks and country guitar and piano. The idea of Haim also adds an appealing ethnic tinge to Swift’s Jumbotron look of suburban Pennsylvania princess towering above a chorus line of mixed-race-and-gender dancers. See, these are Taylor’s Jewish friends. When the number is over, the sisters disappear into a hole in the stage, and then Swift re-appears in a Wagnerian black witch outfit, invoking the spirit of the Rhine for what appears to be the Aryan Nations portion of the show. The song, “willow,” from her 2020 album evermore, has a knock-out final stanza that remarkably could have charted into any decade of American music since the First World War.

“Yeah, that's my man

Every bait-and-switch was a work of art

That's my man

Hey, that's my man

I'm begging for you to take my hand

Wreck my plans, that's my man”

In recompense for his sins, or perhaps for her talents, Swift is now lost in some witchy hellscape, where it’s snowing in August.

“Oh wow, you know,” she says, returning to her safe place, which is her audience, 70,000 strong. “Musically speaking, we’ve got a lot to catch up on. It’s been five years.”

“But let’s not talk about me anymore. Let’s talk about you. There are performances I see in this crowd tonight that are Tony Award-level,” the star confides. I’m up here, and you’re down there, she acknowledges, but what separates the performer from her audience is not that her inner life is any more elevated. Her feelings are shared female territory. What makes her unique is that she’s a hugely-talented songwriter who works incredibly hard at her craft, and there is something endearing about Swift’s evident desire to make that point plain, too.

“I’ve been writing songs since I was 12,” she says, matter-of-factly. “My way of coping with stuff is that I go through something, and then I write songs about it.” The fact that the stories in her songs are real is part of what makes them good though, just like any rap star, a fact she underlines by launching into “champagne problems,” a song inspired by her ill-fated Kennedy liaison. She’s a nightmare dressed like a daydream, or so the song says. “She would've made such a lovely bride,” she sings. “What a shame she's fucked in the head.”

Maybe she is, and maybe she isn’t. Maybe it’s the guy’s fault. Either way, it’s impossible not to be struck by the perfect construction of the line, and by the delicate emotional line that the song walks — between seeing herself through the eyes of her detractors and admitting that she is nuts. In addition to having exquisite control over her craft, Swift is a talented emotional acrobat who is continually walking lines that are finer than they look. The combination of those two talents makes her a star.

It’s also the reason why Kanye West, perhaps Swift’s most serious pop star rival and emotional lightning rod over the past decade and a half, famously targeted Swift at the MTV video awards, claiming that the award she won belonged to Beyonce. It was not a simple matter of black vs. white, which is the war that America’s elites want the rest of the country to fight, and which both West and Swift have, for the most part, skillfully evaded and undermined. Rather, West recognized Swift as a legitimate creative rival, in a way that neither Beyonce nor her husband, the rapper Jay Z, could ever be. Like Kanye, Swift is a true artist and gifted magpie. Like Kanye, and many other creatively gifted people, some part of the energy of her work comes from some degree of controlled or uncontrolled mental illness. But where Kanye, as a black man, is expected to act out like a child in public, so that the powers that be can display their magnificence by excusing his behavior, or not, as a white woman Taylor Swift is expected to keep her shit together, or else. In Kanye’s mind, that gave him the advantage, allowing him to rush the stage, and have his reaction be acclaimed as virtuous, or at worst as a form of careless hijinks.

Time has now proven otherwise. Kanye West is now a basket case, while Taylor Swift is nearly bulletproof. Because she is white, and a woman? Sure. But only to the extent that her belonging to those categories gave her less of a margin for public acting-out, thereby forcing her energies back into her music.

By 9:30 pm, the concert has hit a lull, allowing me a moment to look around at the audience. It means a lot to them to be here. Fortunately, their chosen idol is both gifted and a hard worker, who is willing and able to take their burdens on her shoulders. But nothing about the relationship between 70,000 people in a football stadium and a pop star in glittery outfits can ever fill the holes left by the disintegration of families and communities, which is the promise for which people are willing to pay $1,500 and up per ticket. Which makes the entire evening a lie.

A burst of static lights up the big screen, followed by black and white footage of someone walking in high-heeled boots, and screams from the audience. It’s “delicate,” from 2017’s reputation:

“Third floor on the West Side, me and you

Handsome, you're a mansion with a view

Do the girls back home touch you like I do?”

Eight bridesmaids or whatever they are swan around their lonely queen. Please don’t be in love with someone else.

The last half of the show is devoted to Taylor’s Red Era, consisting of the bouncy girl pop hits with a taste of blood that made her famous, every one of which has become a pop culture tagline — “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together,” “I Knew You Were Trouble,” “Shake It Off,” as well as “Blank Space” — the song that probably did the most to establish Swift’s off-kilter persona:

“Got a long list of ex-lovers

They'll tell you I'm insane

But I've got a blank space, baby

And I'll write your name.”

The end of the show is where artists traditionally position their Greatest Hits in ascending order of popularity and fame, ensuring that the audience leaves on a high. Shoehorning Swift’s most popular songs into the final quadrant of her performance is also a test of her fans’ fealty not just to her persona or a few catchy radio singles but to the entire breadth of her catalog. Tonight, her audience passes the test with flying colors, appearing to know all the lyrics to the 40-odd songs that Swift performed by heart.

More subtly, it is also a declaration of independence from the most important man in Swift’s creative life, Karl Martin Sandberg, known professionally as Max Martin — the biggest hit-maker on the planet. Since the late 1990s, Martin has dominated pop the way The Beatles once dominated rock. Fittingly, Max Martin is tied with Beatles producer George Martin for the most Billboard #1 hits — each Martin having 23. But where George Martin earned the title of the Fifth Beatle, putting him on a par at least with Ringo, if not with John and Paul, Max Martin has always been assumed to be the true author of the incredible string of hits he has been writing since the late 1990s, from Britney Spears's "...Baby One More Time" to "I Want It That Way” by the Backstreet Boys. Perhaps Martin’s greatest success came with Swift’s Red album and the follow-up 1989, setting a narrative that Taylor Swift is a pop culture puppet, manipulated by the Swedish hermit Max Martin and his protégé Karl Johan Schuster, known professionally as Shellback.

The idea that Swift is a ventriloquist’s Barbie manipulated by a pair of hit-making Swedes from behind studio glass is a meme made all the more tempting by the fact that it is true to at least some extent of many of her earlier and best-known hits. Beneath its surface plausibility, the idea of Swift as a puppet is clearly a lie. Her gestalt, her pose, her angle of approach to her material, are deeply her own. Her more recent collaborations with other songwriters — including her boyfriend, the handsome British actor Joe Alwyn, with whom she broke up during the Eras tour, and her longtime partnership with talented Bleachers front-man Jack Antonoff, who resembles a kind of suburban New Jersey version of Ira Gershwin — have only underlined how much of her music, including her earlier songs, comes from within. The collaborators are there to add finishing touches, suggest melodies, or suggest better lines. But Swift isn’t a parasite — she’s the host.

The subtle intelligence with which Swift has handled her Max Martin problem is proof that she is not, in fact, crazy. Working with producers is what pop stars do, and Martin is the best pop music producer in the world — or maybe the best music producer in the world — with a special feel for the distinctive vocal and emotional range of Swift’s voice. While Martin has been dumped by stars before, like Pink, none of them achieved anything like the success that they enjoyed under his tutelage in going their own way. On the other hand, the idea that Martin is Swift’s puppet-master is toxic to the mythos of the girl in sweatpants writing songs about heartbreak in her notebook. So what to do?

Swift’s answer has been brilliant — let her new work gradually overshadow her old work, while keeping Martin out at pasture, so he could return for 2017’s reputation, and for her re-recording of the Red album, a move necessitated by the attempt of music manager Scooter Braun, who also manages Justin Bieber, to control Swift by buying her back catalog. The move infuriated the singer, leading her to put out new versions of all her old albums, which her fans gladly bought, while boycotting the versions owned by Braun. Phasing out Martin, but not completely, while playing hardball with Braun, was a task requiring a combination of guts, finesse, and financial coordination that would qualify Swift to lead a large company or a mid-sized nation. Pulling it off made Swift the Queen of an industry in which pop stars are disposable.

“You call me up again just to break me like a promise / so casually cruel in the name of being honest,” Swift is ranting now. Where “Cruel Summer” is F. Scott Fitzgerald in three minutes for teenagers at the mall, the 10 minutes of “All Too Well,” Swift’s account of a failed romantic relationship with the actor Jake Gyllenhall, is like the girl pop version of “Like a Rolling Stone,” “Queen Jane Approximately,” or any one of a half-dozen other great mid-period Bob Dylan songs about cold-hearted female cruelty. In Swift’s version, of course, it’s the man who is cruel, and she who is injured. What she has learned since her first version of Red is that the cracked baby doll mask that Max Martin so lovingly crafted for her was just another way of deflecting vulnerability, which the older Swift embraces as a mark of her independence. The Taylor Swift of Red takes responsibility for her own feelings, which only makes them more immediate and raw.

If there is something exhausting, for a man in the audience, about nearly three hours of non-stop female emotional shadowboxing and politicking, there is also no denying how completely Taylor Swift has mastered the art of being a pop star, at a moment when Americans in general, and single American women in particular, seem paralyzed by a pervasive uncertainty that has rendered them mute. Meanwhile, Taylor is free to return to her roots, which brings us to folklore, the alt-country pop record she released in 2020, at the height of COVID lockdowns.

“I hit my peak at seven feet / in a swing / over the creek / I was too scared to jump in,” she sings to a childhood friend, before wondering if there is still sweet tea to drink and other beautiful things left in this world. Sure, Taylor. Except, Swift knows that putting her childhood innocence out there is more than just a matter of pressing a button. It’s also a way of rebuking the vampires, which is why the song itself, with its hints of her friend’s troubled home life, doesn’t come off as corny, but as wistful and defiant. There are things that Swift refuses to defile, and in fact holds sacred.

Taylor Swift will take her stand. She’s still the most famous woman in the world, even if her job, as a songwriter, and a pop star, is to be miserable. She can be famous and live in a mansion by the sea in Rhode Island, a safe distance from the Kennedys, but she can’t have it all. The rules won’t allow it. Her fandom depends on her not to lie.

Happiness may not be in the cards for Taylor Swift, but she can still write songs about her mansion. In “the last great american dynasty,” Swift ventures into narrative history, telling the story of her house’s famous owner, Rebekah Harkness, a middle-class St. Louis divorcée who married the heir to the Standard Oil fortune. “The doctor had told him to settle down / it must have been her fault his heart gave out,” Taylor sings, marrying the gold-digger and the woman unjustly accused in a single line. The best song on the album, “illicit affairs,” offers another bracing dose of Nashville honesty:

“...that's the thing about illicit affairs

And clandestine meetings and stolen stares

They show their truth one single time

But they lie, and they lie, and they lie

A million little times.”

Being locked in a private world of deception with someone has its moments, but then you have to pay. “illicit affairs” is a song that Patsy Cline could sing without batting an eye, though it’s hard to imagine Nashville’s original sweetheart curling up in a fetal position near the edge of the stage.

Having abandoned the banks of the Rhine, Swift’s retinue of eight tiny gender gremlin dancers flutter around the Queen Bee up on the Jumbotron. She has effortlessly conquered Seattle, and every other city on her tour, by unapologetically being herself, the girl next door — off-kilter, unlucky in love, with a pronounced vengeful streak, and definitely on antidepressant medications. She is a modern update on Leslie Gore. At the same time, she is hardly noir material; she is not Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity, or Lana Turner in The Postman Always Rings Twice, even if she’s been around the block a few times. There is nothing predatory or even hardened about Swift. Her promiscuity and dagger-sharpening betray a fundamental innocence and hopefulness about the way the world works, or should work, or could work, or would work, if not for the demons in her head, and her bad taste in men.

The stage is set for a fire-works barrage of Swift’s greatest hits, beginning with “cardigan” (“When you are young they assume you know nothing”), to “Style” (“I got that good girl faith and a tight little skirt”), to “Blank Space,” the anthem for a generation of thrill-seeking crack-brained women (“Got a long list of ex-lovers / They'll tell you I'm insane / 'Cause you know I love the players / And you love the game”), to “Shake It Off” and “Bad Blood,” the pillars of the forever soundtrack of every high school reunion from now until the end of eternity. It’s hard to wish for more; at the same time, it is impossible not to wish for more, which is the paradox that Swift proposes. Looking down from the cheap seats, at a mere $1,500 a pop or whatever my friend paid for my ticket, I gladly accept Swift’s challenge.

Come back home to me, America. I know we can make it work this time, at least I hope so. Taylor Swift, in her crazy lady mansion on the sea in Rhode Island, built during the last Gilded Age, is hoping so, too. Come back to me, my love. Don’t let the maniacs slice up your eyeballs with razor blades, like they are promising. The ocean is calling you.

Up on the Jumbotron, Taylor Swift is swimming through the waves like Esther Williams, thanks to some kind of projection trick that has transformed the stage into an ocean from which the pop star emerges, miraculously dry. She climbs a ladder towards heaven, into a cloud, from which she proceeds to sing songs from Midnights, her latest album.

“Hi, I’m the problem,” she announces bluntly, before softening the blow with an eruption of glitter. “When I walk in the room / I can still make the whole thing shimmer.”

You can do it, Taylor, I am thinking, from my perch in the nosebleeds. That’s why you need to run the fuck away from here as fast as possible, because the armies of lunatics and psychotics that wander through the streets of Seattle at night are coming for you, too. All those N95 masks and other box-checking tricks won’t save you from the same fate as the rest of us, who refuse doctrines of the perfectibility of mankind and womankind, and insist on the brokenness of the human condition. It doesn’t matter that you work harder than anyone else in the business, or that you’ve been writing songs alone in your bedroom since you were 12. It doesn’t matter how fast you run, or how much money you make. It doesn’t matter, sweetheart. You are a target, because you insist on telling your own stories, and achieved your own success, which is not something that America wants to celebrate, at least not from someone who looks like you, and refuses to let go. Your giftedness, your hard work, are the reasons why they hate you, and will continue to hate you. The craziness is not just in your head; it’s everywhere now. Please run.

Signed, your newest fan.